We are now just five weeks away from the UK launch of Why Politics Fails, coming out on March 30th. You can see the book, pictured on the left - and of course, PRE-ORDER it - here. And I’ve even recorded the audiobook if you fancy hearing my dulcet tones and possible mispronunciations of the names of small Canadian towns. If you’re in North America, head here, though you’ll have to wait until May, though you do get the North American cover on the right. Why Politics Fails discusses the themes of equality and meritocracy discussed in this post. So if you enjoy this Substack, please do a guy a favour.

Today is the last of my data deep-dives drawn from my various ERC YouGov surveys. Hooray! or Alas! you cry. In the next few weeks I’ll shift a bit more explicitly to talking about Why Politics Fails and of course cajoling you to order it. Today, though I want to spend some time talking about social mobility in Britain and whether people really think they can get ahead through their own efforts.

‘Aspiration’ is on the march. Not the actual reality - that would be too optimistic; not on brand for today’s Broken Britain TM. But the word, the concept, the… aspiration. That’s in vogue.

The coming election fight between Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer is likely to feature this word a lot, largely in terms of defining whether Starmer is its friend or enemy. Tony Blair has spent the last year calling for Starmer to help Labour “cure its [..] economic aspiration problems”, advice echoed by Rachel Sylvester. Rishi Sunak is likely to use aspiration as a cudgel - he began his defence of private schools’ tax reliefs claiming that Starmer was "attacking the hard-working aspiration of millions of people”.

I would imagine we will all be very tired of hearing this word by late 2024. So I’ll take the opportunity before fatigue sets in to raise a puzzle. In a Britain where most people are better educated and in ‘higher status’ professions than their parents - pretty much the definition of ‘aspiration’ - why are so many people gloomy about whether they can get ahead?

Social Mobility is on the Rise

Let’s start with the good news. However you slice it - well almost however, as we’ll see - the British public today has ‘moved up’ in absolute terms. Economists and sociologists call this ‘absolute mobility’ - the country as a whole has an educational and occupational profile that looks better on pretty much all dimensions than that of thirty, fifty, or seventy years ago. Today 38% of the workforce are either in professional or managerial jobs, compared to 27% in 2004. Higher education attainment rates skyrocketed in the 1990s. Look at this graph using data from OWID, that shows the great S curve of graduate attainment in Britain over the past few decades. There’s the fuel for a thousand anti-woke columns in The Times and The Telegraph.

And of course today very few of us work in the world of digging stuff out of the ground or making things - you know, agriculture and manufacturing. At the end of the Second World War, fifty percent of the population still worked in these sectors. Today, the service sector stands triumphant.

In this post, I’ll be using data from a YouGov survey I ran as part of my ERC WEALTHPOL project at the turn of August 2022. This is England only and we have just over 3500 respondents. The survey focused on questions about social mobility and so one of the things we did was ask people a bunch of questions about their parents. Not Freud kind of stuff. Nice social sciences things such as, what was the highest education your mother and your father received; what was their occupation when you were 14, and do they own a house (if still alive).

We can then look at how our survey respondents are faring themselves and compare that to their parents. Below I have a few simple cross-tabs. The first ones start with information about the respondent’s mother and father and look at how the respondent compares.

Starting with the first - education - each person has their educational attainment compared to that of their mother and their father, using a simple five point scale (no quals, O-Level/GCSES, A-Levels, undergrad, postgrad). We look at whether people have the same, less, or more education than each parent. The percentages in each cell are percentages relative to the whole table (i.e. they should collectively add to 100).

With education, 41% of British people have higher education than both their father AND their mother. Just seven percent have lower education than both. Almost two-thirds have more education than at least one of their parents and no less than the other. Four fifths of people have at least the same level of education as both of their parents. However you slice it, this is mass educational upgrading.

I know from painful previous experience that people get angry when I call it ‘better’ or ‘more’, or God forbid ‘upgraded’ education. So let’s try a different tack - what about jobs? I use a seven digit scale employed by the ONS coded as follows: 1 for managers, 2 for professionals, 3 for clerical/junior managerial, 4 for sales/services, 5 for supervisors of manual workers, 6 for skilled manual worker, 7 for semi or unskilled manual worker. Then we have 8 for other (?) and 9 for never worked. I am going to be incredibly crude and just assume that this order is meaningful and lower numbers mean higher ranked jobs. And that means if you manage your local bank branch you beat me - congrats. Obviously there are a bunch of different ways we could do this but… I won’t.

What do we see when we look at occupational mobility? Again, forty-odd percent of people are in ‘higher status’ occupations than their parents. Two-thirds are in occupations at least as good as both of their parents. Broadly speaking, there has been occupational upgrading too.

So this all looks rather like social mobility to me. But you are probably thinking, what about housing? Surely that sucks. And the answer is - it’s complex.

Here is a simple table looking at my respondents compared to their (still-alive) parents.

Parents are the rows and children (i.e. the respondents) are the columns. We can see that about sixty-one percent of people who answered this (i.e. whose parents were still alive) were homeowners (the right-hand column). But only about fifty percent of their parents were (the bottom row). Thirty percent of people had upward mobility, only twenty percent downward. Looks like upgrading to me! Also interesting is that there is little relationship between people’s parental homeownership status and their own - indeed this is about as close to a zero correlation as one could find. All rather encouraging. Until…

Until you split this out by age. Here’s the situation for people under fifty in the sample.

Notice that there’s rather a lot of non-owning under-fifties (the left column) - well over half. There is also a small correlation between your parents owning and you doing so. Not huge, but there. And while only 18% of people have ‘moved up’, owning a house when their parents didn’t, 30% of people have ‘moved down’. Here’s the situation for people over fifty.

Now we see huge mobility. Almost half my over-50 respondents were upwards movers - their parents hadn’t owned but they did (and remember this is excluding people whose parents had died by the time of the sample, which I am guessing is, at the margin, negatively related to home-ownership). Just 7.4% of people were downward movers. So for the older Gen Xers, Boomers and Silent generation this was an era of wonder. They became a home owning society. Their children, not so much. And it’s age, as we shall see, that is at the root of Britain’s aspiration paradox.

The Aspiration Paradox

Most Brits are substantially better off than their parents - education-wise, job-wise, and maybe even house-wise (with all the caveats from above). So how do they feel about social mobility? Well…

Here is a figure from a question we used in the survey which asked respondents to pull a slider between zero and ten to where they felt best represented their views in response to the question “A person’s position in society is mostly the result of…”, with zero being “individual effort” and ten being “elements outside their control”. The histogram below shows that many Brits love to straddle the fence - five is the modal answer - thanks guys. But forty-three percent of people give a six or above, whereas only thirty-one percent give a four or below. The former group I will call the “outside control” people as shorthand.

This all raises an interesting question (well, interesting to me; one hopes perhaps to you too). If aspiration has manifested ‘on the ground’ as it were, why don’t people think individual effort matters. Why do mysterious forces outside their control matter?

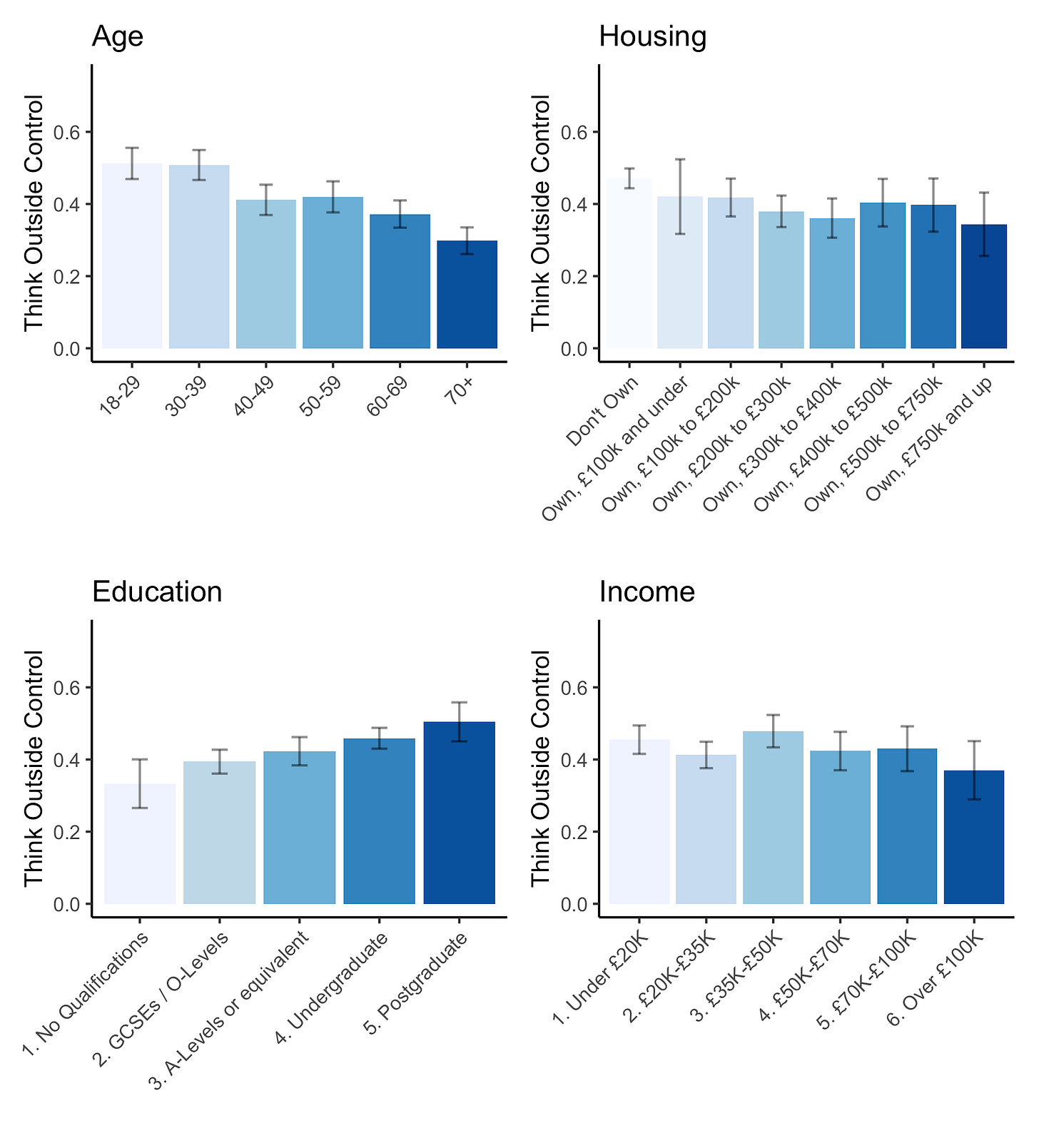

The answer is, of course, that it depends who we ask. Here are a set of demographics. And they tell a funny story. Income and housing don’t actually seem to be hugely predictive. I think it’s fair to say that renters have slightly higher chances of picking ‘outside control’ than owners of expensive houses but the gap is not huge. Income is basically a bust (though interestingly it does matter in a statistical regression where we control for everything else - higher income people are less likely to say ‘outside control’ - but I won’t subject you to a regression table).

The big action is in our friends age and education. And as we shall see, it’s mostly age doing the work. I covered this briefly in an earlier post so I won’t dwell for ages - but there is a twenty point gap between the youngest and oldest groups. There is a very slightly smaller, but reversed, gap between those with no qualifications and those with post graduate degrees. You can probably see where I’m going.

That’s right the education effect is actually basically just age. That’s true if you run a statistical regression (as noted above - it’s age and income doing most of the work, especially the former) but it’s easy to see if we just split people out by those with and without undergraduate degrees. In both cases there is a sharp decline in believing success is outside one’s control by age. It is, I’ll warrant a bit larger for degree-holders, because young degree-holders are the most likely people to say success is outside individual control - over sixty percent agree, compared to thirty-five percent of 70+ graduates. And I will simply remind you of the graph of higher education expansion from earlier - the two bars on the left of the degree-holders picture are made up of those very people who comprised the S-curve in university enrolments. They got degrees but they are Britain’s pessimists about individual effort. We’ll come back to this.

It’s worth looking at a few other factors. In the past I have created slightly mad MRP maps and no, I’m not doing that here. One good reason why not is that there are very few regional differences - basically only London looks different and I put that down to young people.

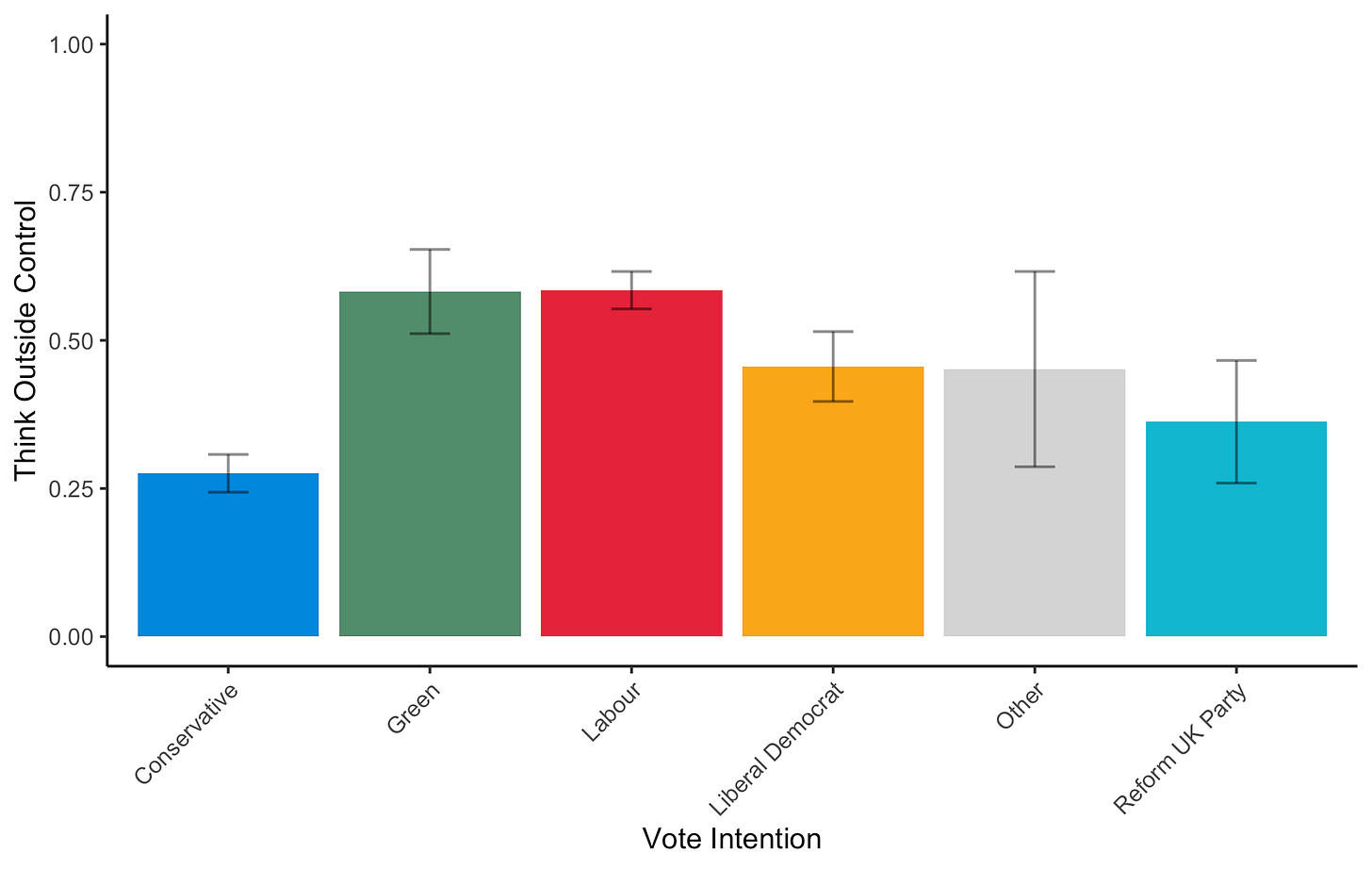

As for partisan differences, they are what one might expect. People who intend to vote Conservative are very unlikely to suggest one’s place in society is due to outside forces. Just a quarter agree. By contrast about sixty percent of Green and Labour voters agree. Lib Dems are LOL, in the middle.

What Do People Say?

Like in the last few posts, I’m able to talk a little bit more about how people reason and think about individual effort and social mobility. Once more I asked people to provide a sentence or two explaining their choice on the slider. With that text data in hand we can look at word clouds where we get what we might expect - ‘work’, ‘hard’ (I am presuming these two are related), ‘opportunity’, ‘effort’, ‘education’.

And with bigrams we can confirm that ‘hard’ and ‘work’ do indeed go together - in both directions, amusingly enough.

So obviously people are using similar concepts and words - fine. But how do they differ? As in previous posts, I can split people into different groups and look at words particularly associated with being in that group (kind of like a chi-squared test). We could do this a bunch of ways but you haven’t got all day so let’s stick to age - again using fifty as our threshold.

We begin with single words. Over fifties use words such as ‘work’, ‘achieve’, ‘reward’, ‘prepare’, ‘effort’ - alright, alright, I get it Dad. Under fifties use ‘wealthy’, ‘poverty’, ‘connection’, ‘bear’, ‘rich’, ‘social’.

We can do this with pairs of words too. Over fifties say ‘work hard’ ‘place right’ ‘right time’ (hmm… wonder if those are connected), ‘can achieve’, ‘get work’. Under fifties ‘matter hard’ (which I am assuming is ‘no matter how hard’), ‘people’s control’, ‘generational wealth’, ‘external factor’, ‘cost live’, ‘house market’, and the mysterious ‘play big’.

OK let’s go from words to sentences. I run a structural topic model, the details of which I won’t bore you with but suffice to say, the computer fits words into ‘topics’ and then plucks out sentences for me that are good examples of those topics. Topic 8 here is one that is very ‘pro effort’ - and I’m going to guess probably mostly over fifties at least in the case of our first, abstemious, answer.

Topic 3 on the other hand is emblematic of the ‘outside control’ answers, focusing on the connections that well-to-do people are presumed to have and with a rather jaundiced view of individual opportunity.

So What’s Bugging Britain?

My two previous posts have been, I think it’s fair to say, not entirely encouraging for those people wanting a New Jerusalem where wealth is taxed, houses built, and a happier, fairer society emerges, etc etc. Sorry.

But this set of data I think has a different implication, one a bit more promising for the would-be reformer. Because on the whole, British people may not want to build houses and they may not want to tax wealth, BUT they do think, on average, that success in life comes from forces outside one’s control. And whereas average support for building houses or taxing wealth was closer to the preferences of the old, this time, the public look more like the young.

So why are the young so upset? We saw earlier that they are better educated than their forebears, and maybe also in higher status occupations. Shouldn’t they be happy?

Mismatch?

Well the first reason is that the extra education may not be translating quite so smoothly into better jobs - either the type of job or the pay. In one sense this is almost inevitable. Not every young person can go into jobs that were previously reserved for degree-holders if the number of graduates is expanding massively but the number of those jobs isn’t. Now it could be that jobs that didn’t require degrees in the past (engineers, journalists, etc) might be done better by people with degrees and so this is all efficiency and productivity raising. But it could also be that people are entering jobs of lower status than they expected when they received a degree.

My Oxford colleague Jane Gingrich and I call this ‘mismatch’. We calculate whether you are mismatched graduate by seeing if you are in a job that used to be largely staffed by graduates in the early 1990s. If you’re not, we call you mismatched. Now, with the way we calculate this, mismatch almost inevitably has had to increase over time since those job-types haven’t expanded proportionally. But the advantage is that it does keep this designation constant.

So how does Britain look in terms of mismatch? Not particularly bad to be honest. The figure below, using ECHP-EUSILC household panel data from across Europe between 1993 and 2012 shows the proportion of the workforce who have a degree and the proportion of graduates in mismatched jobs. I think the overall relationship is not what you might suspect. The relationship is, sort-of, negative. Scandinavian countries in particular seem to have high numbers of graduates in the workforce but relatively low (if fifty percent is low) levels of mismatch. Italy and Austria on the other hand don’t have many graduates but somehow are still not able to find them graduate jobs. The UK has lots of graduates and moderate mismatch - which is… OK I guess.

Why am I showing you this? Well we can use our mismatch coding in broader surveys such as the European Social Survey to see if mismatched graduates differ from matched graduates (and from non-graduates). We look at a variety of measures of satisfaction: with democracy, with life, trust in government, and support for radical right parties. In each case, we find mismatched grads between non-grads and matched graduates. In the case of life satisfaction the mismatched look a lot like non-graduates. But even when they look more like other graduates they still tend to be less happy, less trusting of government, and more likely to vote for the radical right.

All in all then, disgruntled graduates are likely to be a key factor in Britain’s suspicion of aspiration. I should note that I don’t think in any way this means that expanding higher education was a bad idea or that we should limit enrolments or send everyone into apprenticeships. But it seems obvious that graduates with graduate level jobs will differ from those without and we need to take that seriously in any political analysis of the UK or elsewhere (indeed American colleagues will know that the group with ‘some college’ - i.e. didn’t finish - are among the most predisposed to populist right policy and politicians).

Housing?

And then there’s the usual suspect. Yes it’s housing. We saw above that people over fifty in the UK experienced massive upward mobility with respect to housing. But for people under fifty, downward mobility has been the rule. We asked in the survey whether people thought that they had had a fair chance to get the kind of house they wanted and as you can see, only a third of the under thirties agreed, compared to almost sixty percent of the over seventies. And they are all absolutely correct! Access to housing is far lower among younger Brits than it was for older generations. For further reference see essentially every think tank in the UK’s policy pieces on the topic. I won’t dwell here.

Instead, I thought I would do something more nuanced because I have some neat data. We asked people who own a house whether they parents contributed financially to help them buy it. And we also asked current renters if they thought their parents would help them buy. So is it the case that people who were helped onto the property ladder acknowledge they couldn’t make it without outside forces (aka mum and dad) or do they think they did it via their own bootstraps?

The good news for humanity - though I acknowledge it to be the less funny outcome - is that people who received help are much more likely to think one’s place in life is governed by forces outside control. Now this is also quite likely to be because they are younger but I suppose this is encouraging that people aren’t telling themselves false narratives.

What about current renters? Here there are modest gaps between those who think their parents would help and those who don’t. They are definitely not statistically significant differences but I suppose again it’s good that those who think their parents would help aren’t coming up with BS bootstraps claims.

So all in all, I suspect housing is a key driver of why the young feel that getting ahead is outside their control and so an ‘aspiration nation’ probably begins with figuring out ways of getting people onto the property ladder, without inevitably pushing up housing prices by subsidising housing demand like, cough, happened with Help to Buy. But since housing Britain’s original sin, I won’t pretend there are easy answers.

Private Education?

Let’s return in a way to where we started. Rishi Sunak’s ‘aspiration’-based attach on Keir Starmer was about removing charitable status from private schools. Are private schools related to Britain’s tortured relationship with aspiration? Are they good for it? Or bad for it?

We asked a few questions in the survey about private education. Specifically we asked about people’s own experience of private education and that of their parents and their children. And we asked people if they they thought “Is it just or unjust that people with higher incomes can buy better education for their children than people with lower incomes?” Now I recognise this is a slightly tortured way to ask about private education and is a little leading. Sorry. We borrowed it from well-known international surveys. But that’s what we have in any case.

And using answers on this dimension we do find, perhaps unsurprisingly, that people who think private education is unfair tend to agree that individual success is due to forces outside one’s control whereas those who think it is fair (or don’t have a strong opinion) tend to lean towards individual effort.

But here’s something neat - when we actually look at whether people themselves were privately educated, or their parents or children were, there’s nothing going on. Actually receiving, or paying for, private education doesn’t seem to shape one’s views of aspiration, efforts, and outside forces. Instead it’s peoples overall views of the fairness of private education that shape their views about the fairness of society.

Another way to put this simply is that fewer people going to private schools won’t magically make Britain more or less aspirational. So both Sunak and Starmer could be wrong on that front.

Aspiration Resuscitation?

It has, I think, it’s fair to say, been a rough decade for Britain’s young. Policy has tilted towards older citizens; political rhetoric has been dismissive of the young’s concerns and venemous towards perceived ‘wokeism’. But to be truthful the overall picture of Britain’s social mobility - and hence the prospects of young people - is not dark. In many ways, in their education, in the types of jobs they go into, they are better off than most previous generations. But it doesn’t always feel that way. Not least because that shiny new education is not always translating into shiny new jobs, and because the bottom rung of the housing ladder seems to keep sliding just out of reach.

Whoever wins the next election will probably claim to be a politician of aspiration. They will frame aspiration differently. But it’s an attractive concept - and it’s not alien to the experience of Britain over the past few decades. Aspiration isn’t over, but it probably needs a jolt of energy to give the British public hope. And given the current state of the British economy and polity that may not feel forthcoming. But courage mes amis - it’s something to aspire to.