Generation Games

Britain's generations disagree fundamentally. But perhaps not on things that can be resolved.

We’ve just ended the festive season, so you know what’s on people’s minds? Their wonderful/ungrateful (grand)parents/(grand)children. Christmas is a time for generations to come together and stew sullenly about the perceived advantages that people older or younger than you have.

And adding to this seasonal goodwill/badwill the Financial Times’ chief data reporter John Burn Murdoch recently published a widely read article about generational political divides. In particular, JBM argued that Millennials were breaking the ‘oldest rule in politics’ by failing to become more conservative - or to be more precise, more supportive of Britain’s Conservative Party or America’s Republican Party - as they became older.

The proposed culprit for this rule-breaking is… well lots of things. It’s a Murder on the Orient Express style outcome. Millennials are more likely to have gone to university, now strongly associated with voting for centre-left parties. Millennials are also less likely to own houses than they forbears, particularly in the UK, keeping them off the property ladder, whose final rung appears to lead up into the local Conservative Club. And then there’s the generalised culture war stuff - anti-woke, anti-diversity, anti-immigration messaging that turns off the young and turns on the old.

Are these age divides a new thing? Are centre-right parties in the US and UK really doomed as their current voting base dies out and is replaced by younger centre-left voters, who won’t become more right-wing as they age? The survey I ran in October asking about current vote choice (which I discussed a couple of posts ago) showed the following rather stark differences by age group.

In this post I want to explore generational divides in the UK a little more deeply, using a variety of surveys I’ve collected. Bluntly, what we’ll see is that the old and young in the UK are divided more in how they see society and the economy than in how they view government and what it should do.

And that makes this a weird split that, despite its current manifestation in voting preferences, is too deep-rooted for politicians to easily address using the tools they normally wield in terms of taxes and spending. Young and old in Britain largely want the government to spend on similar things. Where they differ is in their views of how fair the UK is, their social attitudes, and their views about contentious but hard-to-solve issues like building houses.

Perhaps this explains why Britain is caught in a kabuki performance where our politicians loudly disagree and polarise along cultural lines, but don’t seem able to push ahead with major practical reforms. Britain’s generations are in a phoney war where they disagree fundamentally with one another on big philosophical issues of fairness, social liberalism, and… well.. the sanctity of the Green Belt, but when it comes to the usual political cut and thrust of fiscal policy, there’s far more agreement.

Does Age Really Matter More?

Let’s start where JBM did, with the political behaviour of different generations. Like John, I have used the British Election Study combined survey back to 1964 and compared the proportion of each generation in each election supporting the Conservative Party compared to the national average (from each survey). But whereas John is looking at how each ‘generation’ behaved by age (so his x-axis was age), I am looking at elections over time and the average vote choice of that generation. So slightly different but along same lines.

What’s the main thing we see? Generations have always voted slightly differently. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, there was about a ten point difference, with older generations more Conservative. But the last decade or so has seen a massive widening of generational divides - a jaws of political death (at least if you were Labour in 2019).

People born before 1965 - the Silent generation and Boomers - and those born after 1981 - the Millennials have diverged massively since 2010, to being about thirty percent points apart in terms of support for the Conservatives. And LOL at the Gen Xers like me who have just plugged along a bit less Conservative than the rest of the population consistently since the mid 1980s. And people said we’d never accomplish anything.

I think this tells a slightly different story to John’s piece in that we don’t really see the Gen Xers follow the same path as the three earlier generations but certainly the Millennials have moved in a completely unprecedented way.

But there’s more. What if we split our generations by their educational attainment? Now it’s worth remembering that precious few members of the Silent generation, let alone the ‘Greatest’, went to university. And I am excluding any group with fewer than fifty survey participants so these groups drop out of the graph below. But otherwise we can now track the generations by educational level. What do we see? With people without degrees, something very similar to last time, albeit with a little jump up by younger generations in 2019 as Boris Johnson proved spectacularly successful in attracting the votes of non-graduates.

But when it comes to people with degrees, all generations have shifted towards Labour. And although the generational gap among graduates has widened a little since the early 2000s, it’s much more moderate. The big age divide we see in the general population is driven to a large degree by different educational experiences. So the reason JBM is finding that millennials are not becoming more Conservative as they age (and I’m finding stability among Gen X) is that they are more likely to have degrees, which pushes them to the left and counters the aging effect. That is a fairly well-known story of course but it’s going to have a bunch of implications for what our generational divides in the UK are actually about (HINT: things that can’t be easily resolved).

The other thing that this analysis shows, which I think is less well-known, is that there is a really large political split by age among non-graduates, which rose dramatically in the past decade and was not ended by Boris Johnson. This suggests that the cultural attitudes of the university-educated class might have spilled over to the non-graduate young, in a way that bodes ill for culture warriors on the right. You could win elections by focusing on older non-graduates - a very large group - but if graduates plus the young becomes a larger constituency… well then you just culture-warred yourself into oblivion.

Culture Warriors?

And so to the culture wars. Last year I ran a bunch of YouGov surveys as part of my WEALTHPOL grant. One I ran in the summer of 2022 on 3500 odd voters in England, which looked at social mobility and fairness. And a second I ran in October 2022 on 3500 or so UK voters, looking at housing and taxation. In future Substack posts I’ll… Oh you get the point.

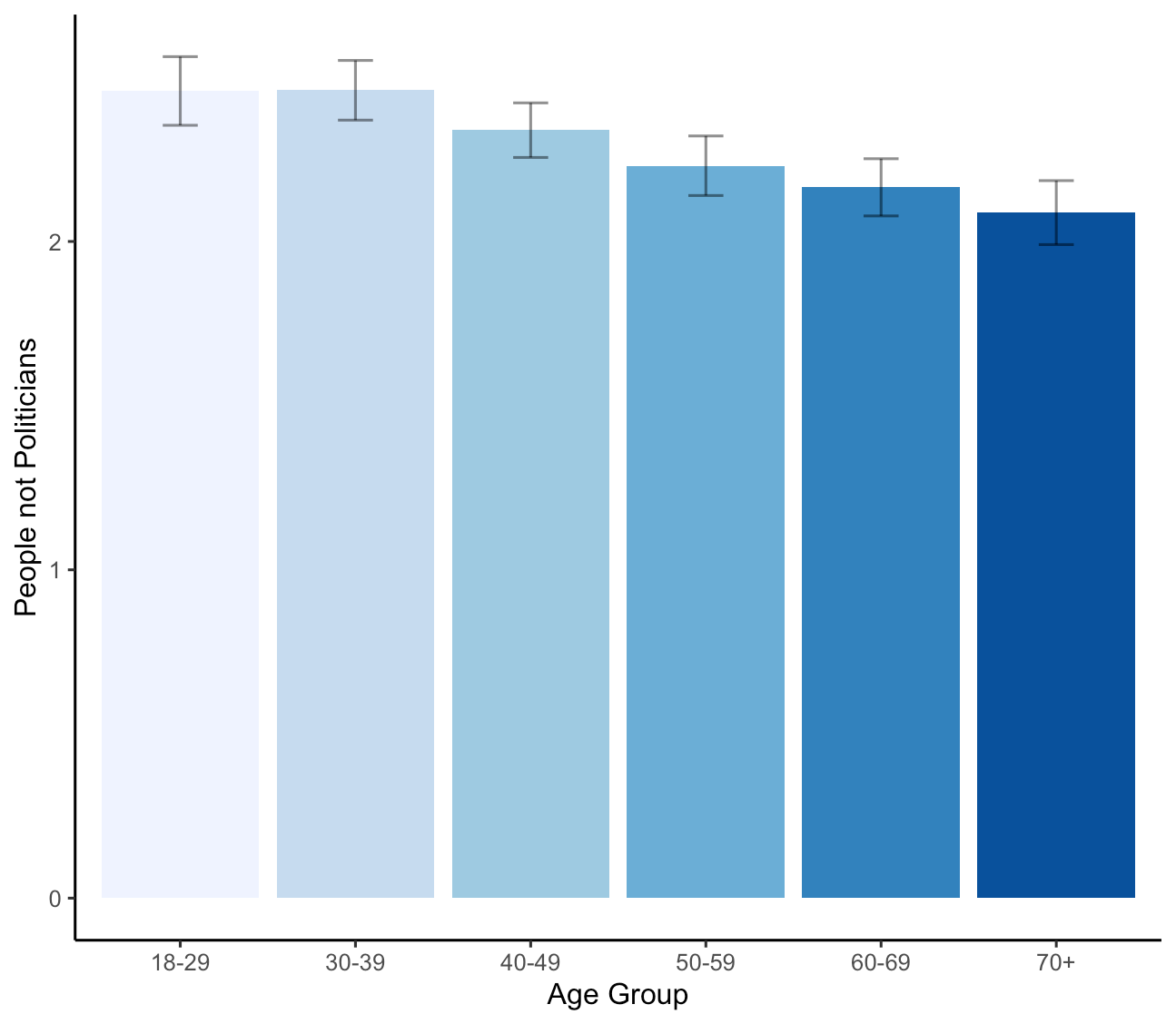

What we care about today is how generations shape attitudes in the UK. In my most recent UK-wide survey, I asked a standard battery of survey questions about social attitudes. Three of these are usually used by survey researchers to measure social authoritarianism - five point scales about whether people agree that (a) “For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence”, (b) “Young people today don't have enough respect for traditional British values”, and (c) “It is more important for children to have respect for their elders than independence”. Given that ‘young people’ of various kinds are involved in these questions, you won’t be surprised to see pretty large age-based differences in how people answer these. If we add them together into a fifteen point scale, you can see below that there is an almost three-point difference in how twenty-somethings answer compared to seventy and overs. If it makes you feel ‘better’ about these questions - the death penalty question accounts for about a third of this difference.

The figure on social authoritarianism might make you think older people are more attracted to ‘populist’ positions than younger people. But that’s not at all the case if we widen our set of ‘populist questions’. Below is a combination of answers to whether people agree (a) “There is one law for the rich and one for the poor” and (b) “Ordinary working people don’t get their fair share of the nation's wealth”. These ‘economic populist’ questions don’t show a great deal of variation - but to the extent they do, older people are less populist.

And that’s even more striking when we look at the final prompt: “The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy”. Here the young are notably more populist than the old.

What these results suggest to me is that older people are indeed more socially conservative but young people are more likely to view the UK as unfair and in need of radical change.

Fairness and Social Mobility

And that’s exactly what we see when we turn to the England-wide survey from summer 2022 on fairness and social mobility. One of the questions we asked was for people to place themselves on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 was the statement “A person’s income and position in society is mostly the result of individual effort” and 10 was “A person’s income and position in society is mostly the outcome of elements outside of their control.”

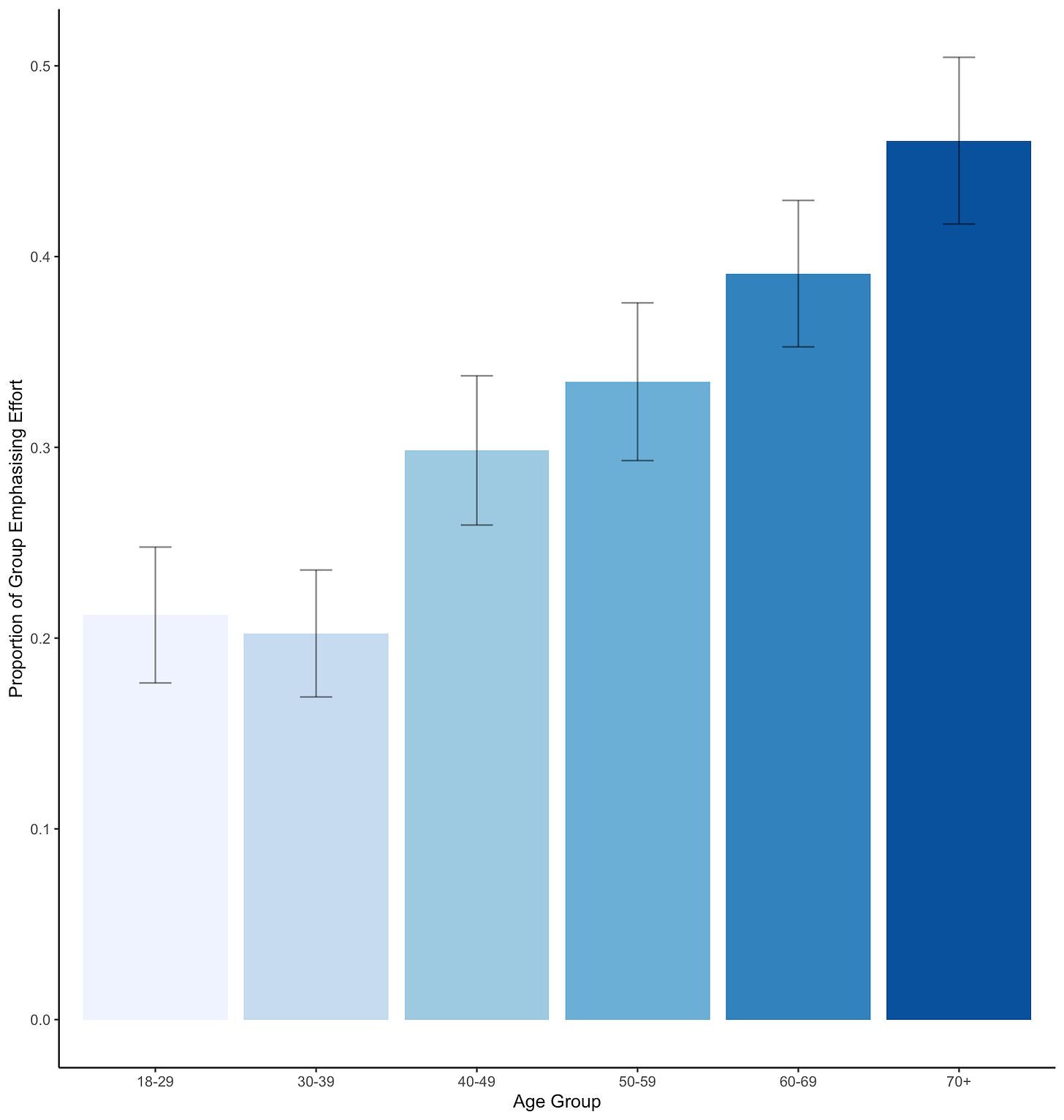

Now, about a third of our respondents did the properly English thing and plumped for the fence-sitting response of 5. Thanks guys. If we focus instead on the people who answered 0 to 4 - (the pro-effort people) and we group by age we see pretty striking results. Whereas only twenty percent of the under-forties took ‘pro-effort’ positions, around half of the over-seventies did.

We can flip this and look at the ‘outside forces’ people, who answered 6 to 10. Here we see about half of the under forties in that group, with thirty percent of the over seventies having that view.

On this fundamental question of fairness and social mobility, British generations are completely divided. The old think they did it on their own (or at least that others should). The young think success is outside their control.

This seems to me to be a pretty stark vision of modern-day Britain. To the degree there is a ‘British dream’, the mostly retired think it exists and those entering the workforce think it’s a sham.

Can we get any further at explaining this divide? We asked people about whether they thought that they had had a fair chance at (a) achieving the level of education they were seeking, (b) the job they were seeking, and (c) to buy the house or flat they were seeking. In the gallery below you can see that most English people felt they had a fair chance at education and this doesn’t vary much across age. But with regard to jobs, there is an emerging split, with the retired very much more in agreement that they could get the job they sought. The big difference, you won’t be surprised to hear, is in housing. Fewer than a third of the under thirties felt they had a fair chance at buying a house. Almost sixty percent of over-seventies felt they had had this chance.

This also turns up when we asked people if they were better or worse off than their parents with respect to education, financial situation (rather than job), and housing. Everybody agreed they were better off in terms of education. That’s because they all have been! Educational quantity and quality has improved massively in the UK in the past half-century. However, in terms of financial situation and even more so housing, the generational divides are stark. Under fifties think they are worse off than their parents in terms of housing. The over-seventies think they are better off. Both are right.

A final way of looking at this is to ask people to compare the generations themselves. We asked people which generation they thought had had the best chances in terms of ‘moving up in society’, ‘best educational opportunities’, and ‘most access to good, affordable housing’. There was widespread agreement that recent generations had had the best access to education (probably accurate!). And even clearer agreement that the Boomers had been the winners in terms of ability to move up in society and in access to housing.

Housing

Much of Britain’s generational divides seems to be driven by our original sin - a lack of affordable housing. And so you won’t be surprised to hear that there’s no easy solution to that that doesn’t just reinforce these divides. In our October UK survey we asked people: “Thinking about new housing in your local area. How much would you support or oppose more homes being built in your local area?”

We learn a couple of things from this. First off, there is no real interest in Britain in building new houses - at least where people actually live. No group had above fifty percent agreement with this prompt. Second, there is a generational difference of about ten percent points between the young and old. Whereas in earlier figures we have seen the over-seventies standing out that’s not true here. Gen Xers and Boomers are in an unholy anti-building alliance.

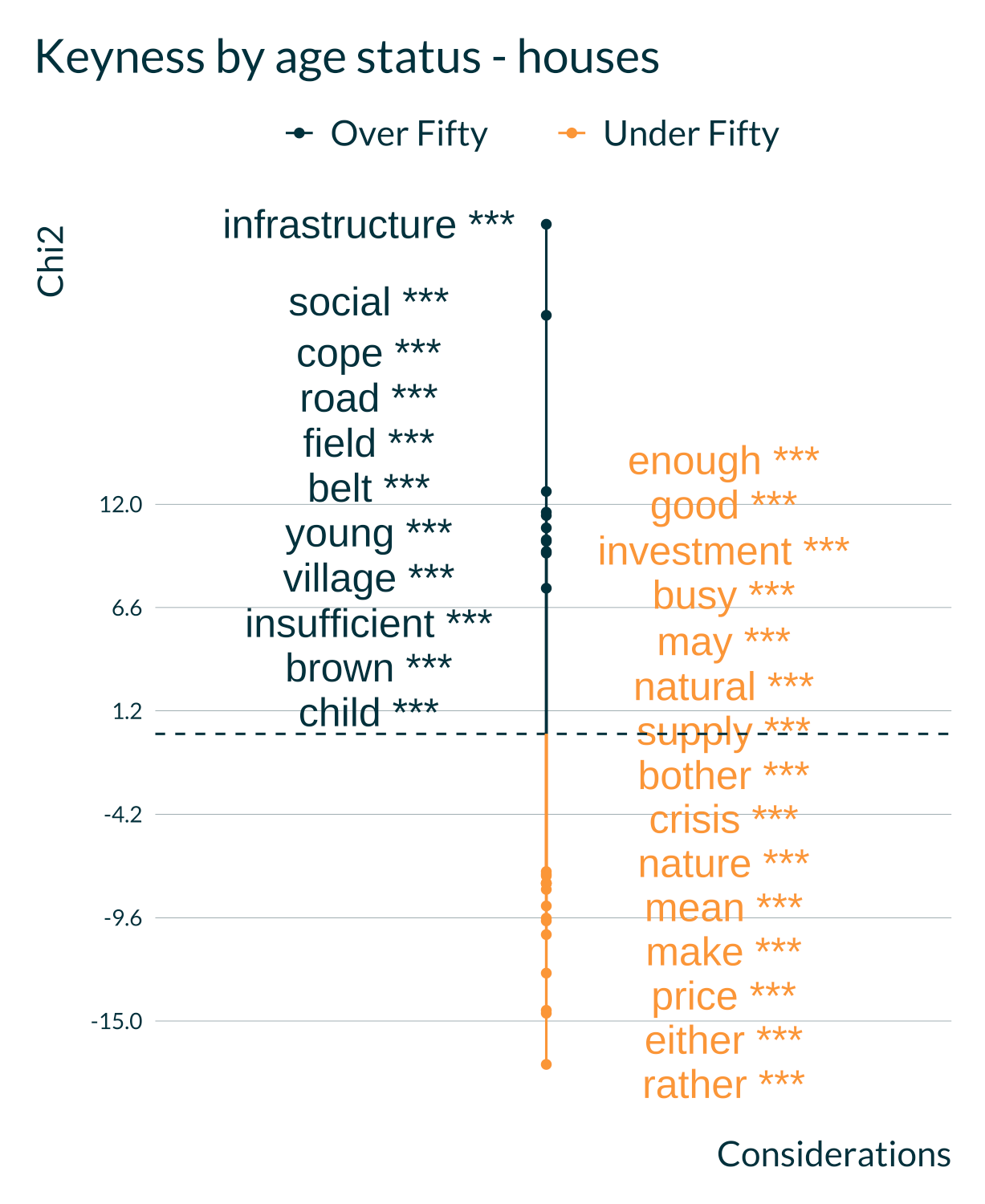

We let people write a sentence explaining their answer. And with that sentence we can do some interesting stuff. One thing is to look for particular words, or groups of words, that are statistically associated with respondents’ age (this is called a keyness statistic). We split by whether people are over or under fifty and look for the kinds of words each group is more likely to use. By far the most over-fifty specific word is “infrastructure” - we also see “cope”, “road”, “field”, “belt” (not clothing I would imagine), “village”, “insufficient”. Under-fifty specific words include “price”, “crisis” and a bunch of weird words like “either” and “rather” which <throws up hands>.

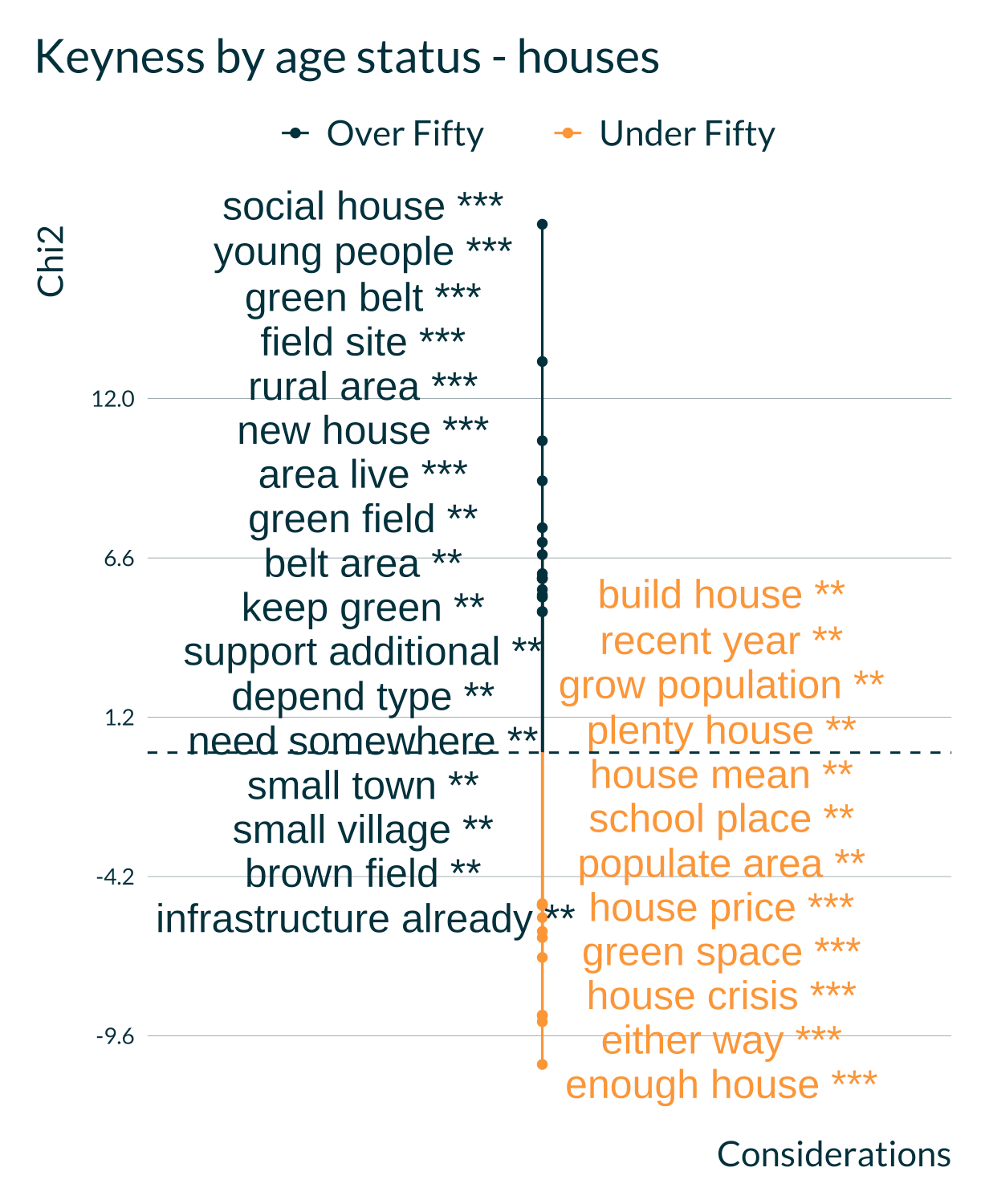

We can also do this for pairs of words (bigrams). Over-fifty specific bigrams include “green belt”, “young people”, “field site”, “rural area”, “support additional”, as well as the more ambiguous “social house”. Under-fifty specific bigrams include “enough house”, “house crisis”, “house price”.

I don’t want to exaggerate these differences. We already saw there is limited support for building houses in people’s local areas, even among the young. But how people use language seems meaningful, especially in terms of following reasoning. In turn it indicates just how hard it is to convince people to build new housing - if people think you can’t build in ‘rural areas’, there’s not much you can do to change that.

Where we Agree

Britain’s generations may be divided in terms of voting, social attitudes, feelings of fair treatment, and over housing. But but but. I said above that when it comes to economic policy - you know, the stuff government does - it’s not quite so bad.

Let me give a germane example. You might think that differences over building new houses by age would filter into views about the government’s responsibility to build new houses. But, they don’t. Everyone think s the government should indeed be building new houses. Just presumably not near them.

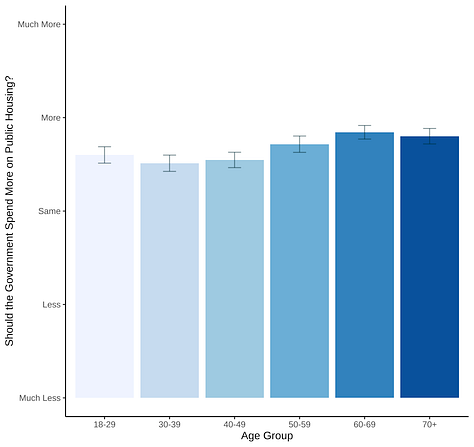

And when it comes to the level of government spending, all groups apparently agree the government should be spending the same or more on (a) public housing, (b) public education, and (c) support for industry.

So if we push people on what they think government should do, many of Britain’s generational divides go away. That could simply be a result of austerity fatigue. But it’s an odd contrast with the stark differences in non-policy beliefs like social attitudes and views on fairness. It suggests we remain far apart at a philosophical level but perhaps much closer on an operational one. Whoever wins the next election, that I guess is the good news.