A Puzzling Inheritance

Why, in a world where wealth matters more than ever, we want to tax it less

Many thanks for subscribing to, or just visiting (and, you know, then subscribing to) this Substack. Last time around we looked at why it’s so hard to build houses in the UK. This post dives into a closely connected question - why is it so hard to tax wealth? Especially when there seems to be so much of it, so unequally distributed? And like last time this will be a deep data dive into original survey data (yes with another MRP and text analysis, you lucky people), but also with a broader view of wealth inequality and taxing wealth around the world.

Every week also brings us closer to the publication of Why Politics Fails, coming out in the UK on March 30th. You can see the book - and of course, PRE-ORDER it - here. Or if you’re in North America, head here. If you want to read the book in German, Japanese, Korean, Spanish, etc - well, I’ll let you know when I have links! Why Politics Fails has a whole section devoted to the challenges of responding to wealth inequality, drawing on some of the data here. So if you enjoy this Substack, please do a guy a favour.

A couple of weeks ago, the memorably named ‘Patriotic Millionaires’ rocked up at Davos to request something rather unusual. Here was a group representing some of the world’s richest people - Abigail Disney, Morris Pearl, Steve Silberstein - asking for governments to tax them more. Among other things, these millionaires and billionaires have asked for the creation of a wealth tax, that might tap, not solely the vast incomes of the richest, but their savings, investments and property.

The idea of a wealth tax has been bubbling up over the past few years. Not long ago, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren were both running for the nomination to be the Democrats’ Presidential candidate in 2020 on policy platforms that centred around the introduction of enormous, swingeing taxes on the wealth of the über-rich. And wealth taxation has re-entered British political debate as the probability of a Labour government in the near future rises.

Is a wealth tax an inevitability? Would it be a popular move for Labour? Or even the Conservatives (just kidding)? I’m here to burst some bubbles. Wealth inequality may be extremely high in the UK but that doesn’t mean there is clear popular support for taxing wealth. In particular, although most of Britain’s wealth divides relate to property, inheritance tax remains extremely unpopular. And we’ll explore some of the reasons why.

But it ain’t over. At the end of today’s post, I’ll look at the types of language that might make wealth taxation more popular and what kinds of wealth taxation might be more successful politically. Wealth may be hard to tax - and substantially harder than blithe articles in the Guardian sometimes suggest - but it’s not impossible.

Wealth Inequality in Britain and Beyond

Wealth inequality in the UK is at its highest level for forty years. The top one percent of wealth-holders in the country hold around twenty percent of the nation’s wealth - the bottom half hold just nine percent. The figure below shows the increase in the holdings of the top one percent since the early 1980s using data from the wonderful Our World in Data.

Wealth inequality is far, far higher than income inequality. To give an example, taken from the ONS, while the Gini index for income inequality is just over 0.40 (gross - the Gini for disposable income is even lower, around 0.36), the Gini for wealth inequality was 0.62 in 2020. And that’s total wealth, including houses and physical property such as cars and antiques. The Gini for real estate alone is was 0.66, the Gini for private pensions wealth 0.73, and for financial wealth a whopping 0.89.

With these numbers, it’s no surprise that taxing wealth is very much on the political agenda. In Davos recently, we saw the Patriotic Millionaires advocating that the rich (in their case, people with $1m incomes or $5m in wealth) pay more in taxes. Figures close to the Labour leader, Keir Starmer, have spoken about the possibility of taxing wealth to unlock a stream of state revenues in an era where the tax burden on incomes is high and demands for spending higher.

Given the recent rise in wealth inequality in the UK, and not ignoring the very high level of wealth inequality, why have successive governments found it so hard to tap into wealth as a way of funding the welfare state? Taxing wealth has all kinds of potential benefits - it taxes unearned gains in the value of land; it is hard to avoid (at least on property); it leans into generational fairness, taxing the property boom that benefited the Boomers and has left Millennials, out of luck, out of homeownership.

And yet... And yet… It ain’t so simple.

You see I left out a few things with my earlier graph and figures. Like other countries.

Oh, and the previous century of data.

Still, no harm done.

Once we place the UK today in some kind of context, inequality of wealth doesn’t look especially outrageous. In absolute terms it might seem shocking that twenty percent of the country’s wealth is held by just one percent of the population. But compared to the Britain of W.G. Grace, Emmeline Pankhurst, or George Orwell, or indeed the America of F. Scott Fitzgerald, it’s pretty low.

The turn of the twentieth century marked the peak of ‘Georgism’ - the movement for a single ‘land tax’ led by the American economist Henry George, which inspired the Liberal Party’s People’s Budget in Britain and even an explicitly Georgist party in Denmark. Unequal wealth really was once the core of political debate.

With that said, relative to most of our lifetimes, wealth inequality is indeed relatively high in the UK, USA, and many European countries. And of course, there is far more wealth out there to distribute unequally than there was in 1900. So, being in the top 1 percent wealthiest today means a life of unimaginable splendour compared to your equivalents a century ago. Take that Tom and Daisy.

On top of this, let’s return to the difference between income and wealth. Incomes in the UK and beyond are substantially less unequal than wealth. But governments rely on taxing income, not wealth, for the lion’s share of their day to day revenues.

To give an example, the British government gets 27% of its revenues from income tax and another 18% from national insurance. The government also taxes our spending, most of which comes from our incomes: VAT is 16% and various sin taxes and levies account for another 10%. So what about wealth? Taxes on ‘capital’ for regular folk (as opposed to corporations) are just 3.7% in total, which includes stamp duty on property (1.5%), capital gains tax (1.1%), and inheritance tax (just 0.7%).

We also get our property taxed - sort of - through council tax which accounts for almost five percent of revenues. But council tax is set according to bands of property values established in 1991 and not changed since then. It’s not a property tax set as a percentage of assessed value like in the USA.

So we have highly unequal wealth but we don’t seem to tax much of that. Is Britain uniquely bad? Well maybe in a myriad of other ways but not here.

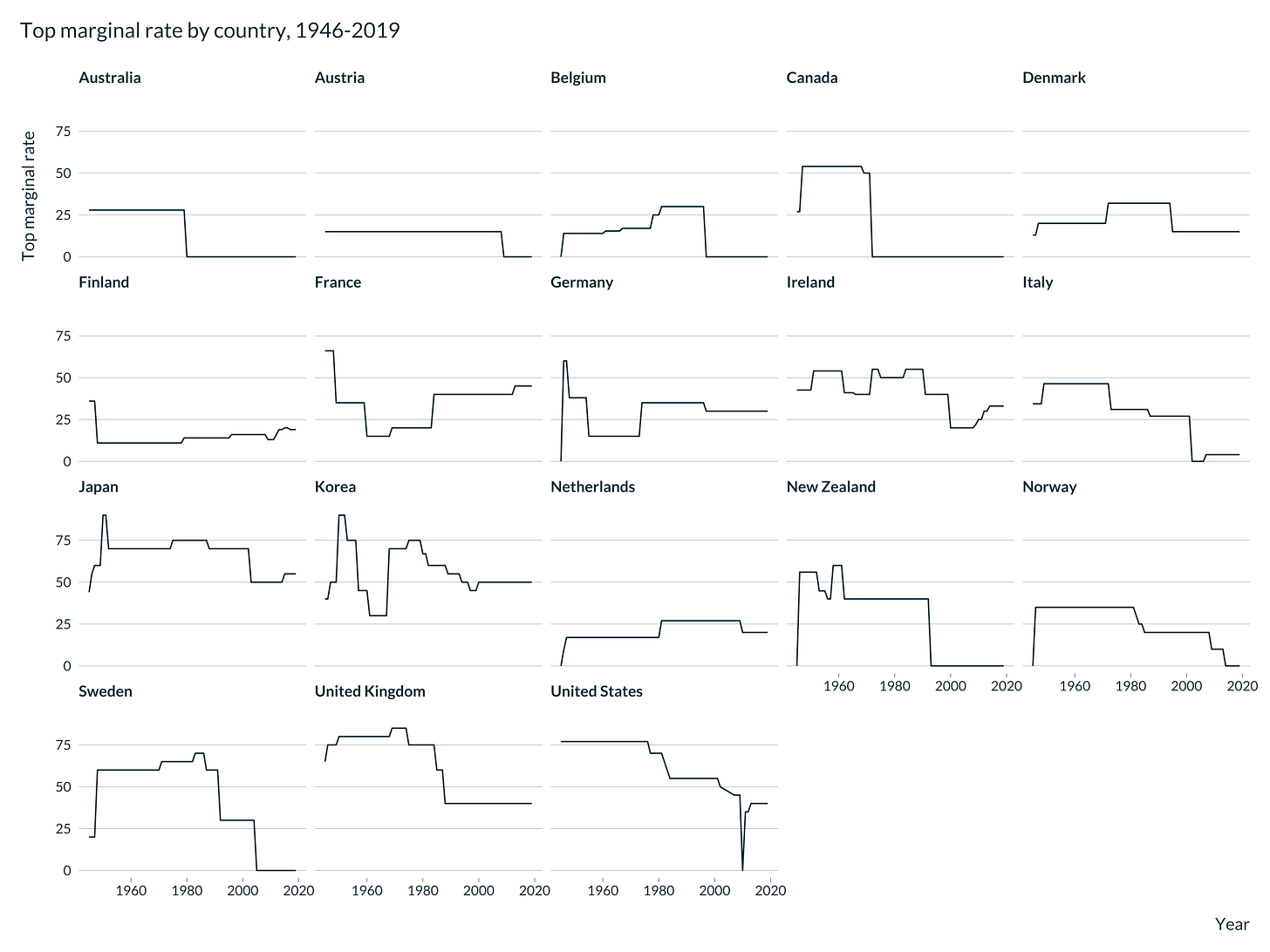

Most countries have fairly minimal wealth taxation, especially as compared to forty years ago. With my WEALTHPOL team we collected data on the oldest (though as we’ve already seen, not always the biggest) type of wealth taxation: inheritance taxation. We have created a unique database of inheritance tax rates for eighteen countries (the standard OECD set of Western Europe, Japan, Korea, North America and Oceania) back to 1945, using primary sources from the relevant countries (available here). In particular, Mads Elkjaer and Laure Bokobza deserve the credit for masterminding this data collection.

So what’s been happening to inheritance taxation during this era of ever-rising wealth inequality and the rise of the mega-rich? Um… The average top rate of inheritance taxation has collapsed.

That’s true of Britain too. Inheritance rates on the largest inheritances have declined here. But actually, as things go, we tax inheritances - above the threshold - pretty fiercely. And you know who doesn’t? Those Scandie socialists - the Norwegians and the Swedes, who have got rid of inheritance taxation. By the way, that weird downward spike in America is when George W. Bush got rid of the estate tax for one year only, after which it shot back to roughly its earlier rate. Which led to a very entertaining Law and Order episode in which people tried to knock off their parents during the year of no estate tax…

What this suggests to me is the Patriotic Millionaires are going have a tough climb. The trend everywhere has been for a collapse in inheritance tax rates (and indeed revenues). Indeed, editorialising here, I have been surprised that during the past twelve years in which they have been in government, the Conservative Party hasn’t considered removing inheritance tax entirely as in a bunch of countries in the figure above. As we shall see, inheritance tax ain’t popular.

What We Think of Taxing Wealth vs. Income

If you are a subscriber or regular reader of these Substacks you’ll recall, possibly in feverish nightmares, that I have been running a series of polls through YouGov to look at housing and wealth in the UK and engaging in lengthy brain-dumps of that data here. If you like that, you’re in luck again. If not… um go buy my book, which is refreshingly dataviz-free.

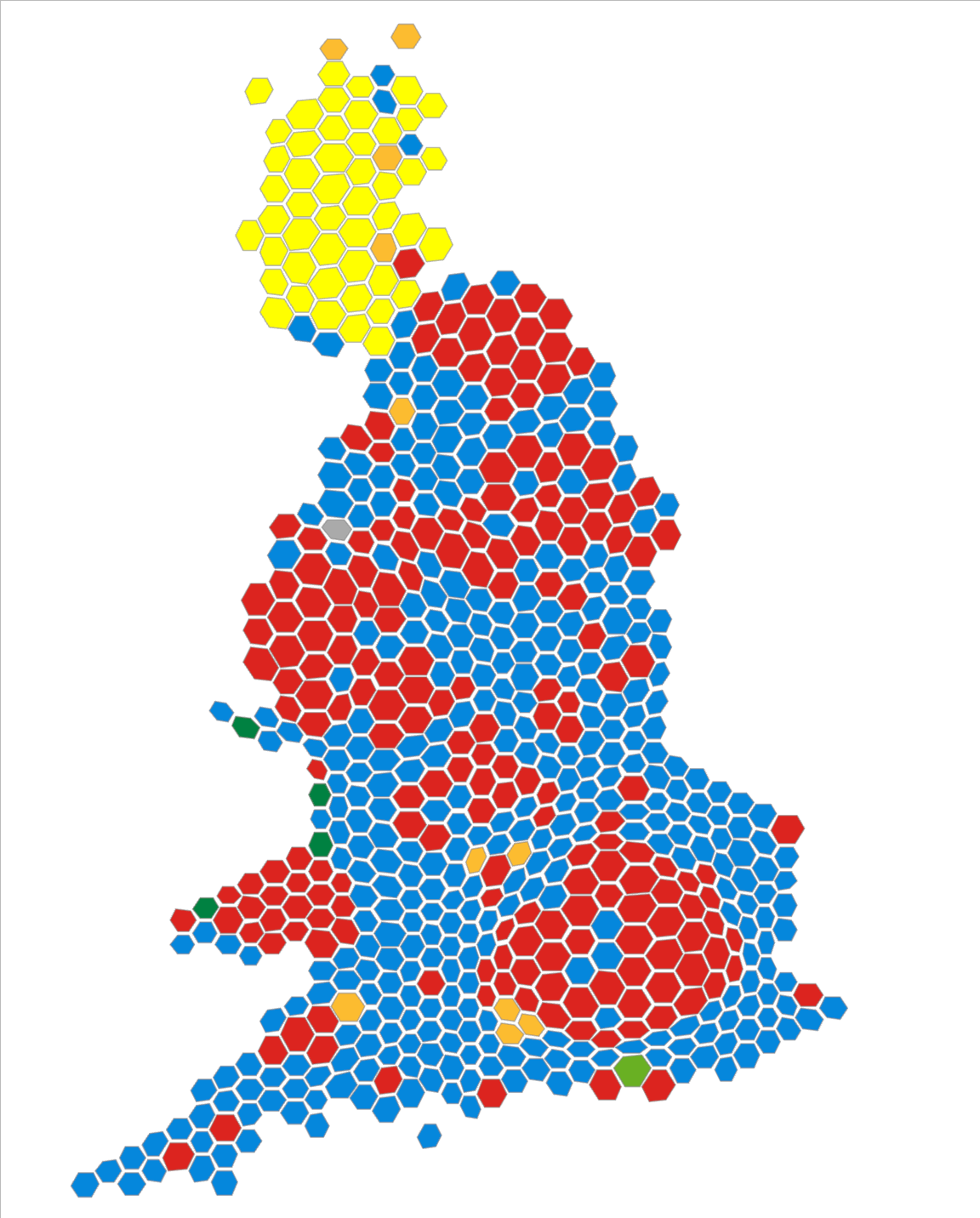

Last time round, I showed the results of an MRP poll that predicted support for building new houses in each constituency in the UK (ex-NI). If you want to know what an MRP is and how it works, knock yourself out on that post. Here, I’ll just prefix it by saying, I am using three polls with 10,165 respondents in total from 2021 and 2022, where I have information on respondent's’ demographics, where they live, and what they think about taxing wealth. I can match that to demographic data at the constituency level to come up with a ‘best guess’ for support for taxing wealth in each constituency. See, that wasn't so bad.

In each poll we asked people the following: “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents a tax system that concentrates on taxing people’s wealth (their property, savings, and inheritances) and 10 concentrates on taxing people’s income from work, what would be your preference?”. And then they got to pull a slider to their preferred point. And afterwards we asked them to enter a sentence explaining their choice. We’ll come back to that. But for now, we’ll use a simpler version of the question, coding people who favoured taxing wealth (0 to 4) as one and those who were indifferent (5) or favoured taxing income (6 to 10) as zero.

The basic take-home is that preferring to tax wealth is a minority pastime. The percentage of people in the survey who prefer to tax wealth is 35.8.%. To provide context, 39.7% of people preferred to tax income and 24.5% of people were indifferent. There is NOT some great silent majority of Brits out there who think we should lay off people’s income, and go after their wealth. If anything, it’s the opposite.

If you’re interested in looking in greater depth at the data from this new MRP, or indeed downloading it, head here. If you’re not, have a look at this pretty map. This is a cartogram of the UK, where each constituency is a hexagon, sized according to how supportive it is of taxing wealth and coloured by who won the seat in the 2019 General Election. If you want to know which constituency is which, you’ll have to go to the link above but you should be able to get a sense of where likes, and dislikes, taxing wealth from the geography of the map.

Broadly it looks pretty similar to what we saw last time around with support for building houses. Labour areas like taxing wealth more than Conservative areas. But there are some interesting differences we’ll see shortly.

Below I have tables of the constituencies with highest and lowest support for taxing wealth. The big-taxers are Northern or Scottish urban districts - classic Labour support bases, plus a smattering of very liberal Southern urban locations. The places that HATE wealth taxation are more Conservative suburbs of London, including my old stomping ground of Orpington (once home of a dry-hill ski slope, where I broke my wrist by crashing into a Coke machine… long story).

This is actually a pretty different mix to those places that wanted to build or opposed building new houses. To remind you of that, the big house-builders were hipster central locations in London and London-like places. This time, the North will rise. And the opposers were in very very Conservative places such as Christchurch and Castle Point. Here we see least support in places that vote Conservative but have very high property prices, i.e. London suburbs.

The cartogram below shows the GAP between supporting taxing wealth and supporting building houses. So big hexes mean you want to tax wealth much more than you want to build houses. And small hexes mean you want to build houses much more than you want to tax wealth. And here we see a really interesting division in Labour constituencies. Those in the North really want to tax wealth, those in the South really want to build houses. Might I suggest that this could be a rather interesting divide in priorities in a future Starmer government…

As I’ve mentioned, if you want to see more of these graphs and to use them interactively to check out your constituency or download the data head here. But now I want to turn, as I did last time, to differences across individuals rather than places.

Below we can see that there a big differences in how people think about taxing wealth by political party (vote in GE19) and in terms of demographics. Broadly speaking the people who dislike taxing wealth voted Conservative (or for Plaid?!?), were over fifty, or owned a house worth over £500k (and hence possibly liable to be taxed under the inheritance tax code). And who liked taxing wealth? Labour voters, SNP voters, young folks, and renters (and owners of cheaper houses). Education and income don’t have especially clear relationships to taxing wealth - maybe people with a lower secondary education are less positive about wealth taxation but I wouldn’t bet my life on it.

We also asked people to justify their choice, as we did last time with housing. Again we get really interesting, well thought through answer in both directions. Here are some word clouds for pairs and triplets of words. You can see some of the themes and differences here: “already tax”, “work hard”, “wealthy people”; and “can afford pay” versus “already pay tax”.

To see the differences in language more clearly we can do a ‘keyness’ analysis where we look at words that are especially associated with particular groups. Here I will do that just for single words. Starting with non-homeowners versus homeowners we can see that non-homeowners use words like ‘hoard’, ‘inequality, ‘everyone’ and my favourite ‘idk’. Homeowners are more likely to use words such as ‘property’, ‘save’, ‘saving’, ‘penalise’ and ‘encourage’. You can get a sense from this about the arguments people made. Non-owners emphasise inequality and the unfairness of ‘hoarding’ wealth. Owners talk about incentives and the unfairness of ‘penalising’ saving.

We can also do this by age. Over fifties use similar words to homeowners (plus ‘retire’). Under fifties use similar words to non-owners.

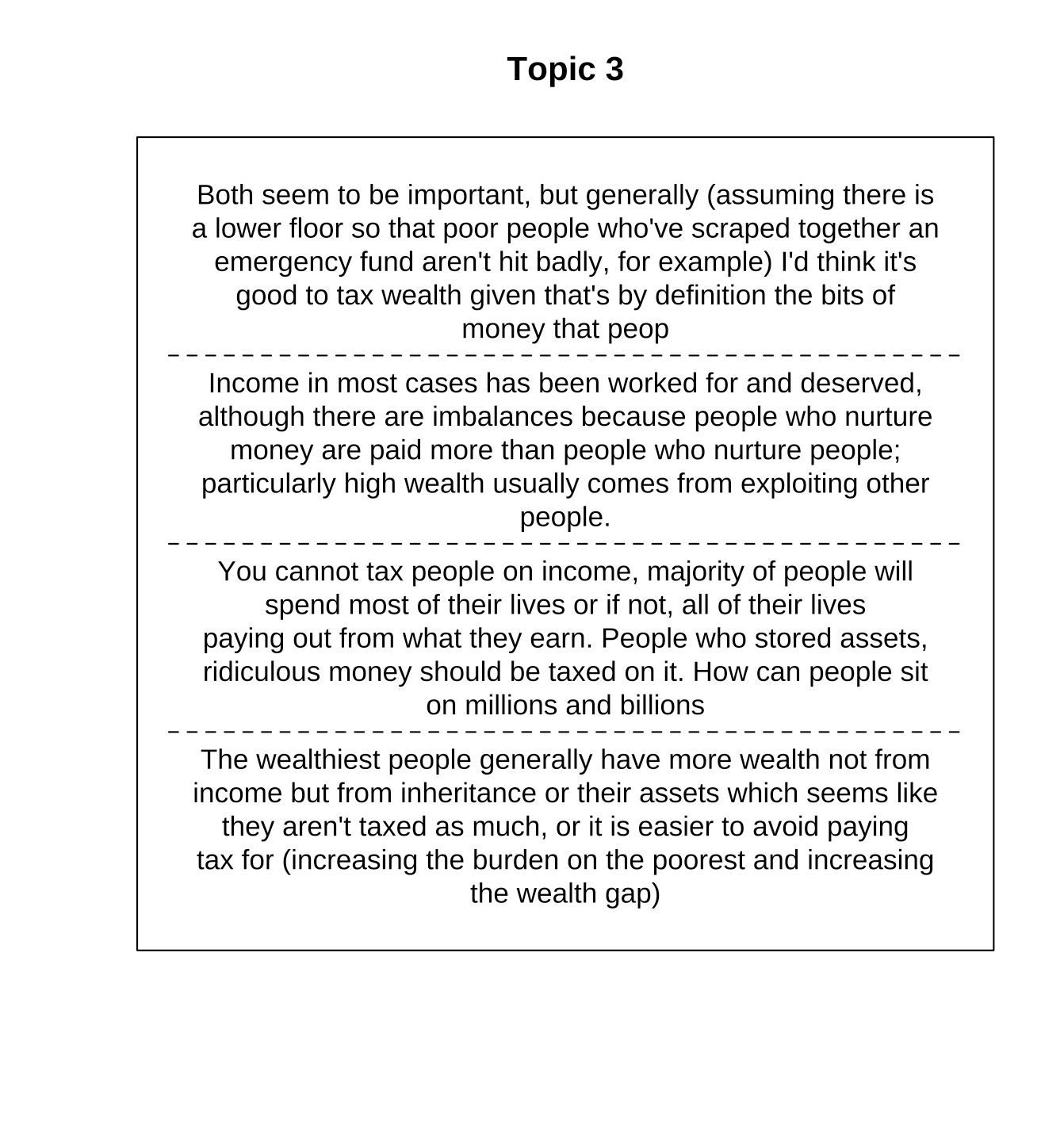

In the case of wealth taxation I find looking at people’s statements even more helpful than just looking at words. Like last time, I conducted a structural topic model analysis where I have the computer sort words into particular ‘topics’ and then pick out statements that are especially good fits for those topics. So Topic 8 here is an anti-wealth tax one. People talk about punishing hard work, the arbitrariness of taxing housing that has appreciated in value, and the challenge of paying taxes on wealth (as opposed to at source).

Topic 3 by contrast is one that is associated with support for taxing wealth. Here people think it’s fairer to tax things that people already have as backup, rather than for day-to-day expenses, and a sense that some people with very high wealth have come about it through unfair means (or not through work).

What’s in common to both, otherwise opposed, positions is that people care about fairness. For some people it’s not fair to ‘double-tax’ income by taxing savings. For others it’s not fair that some people have enormous fortunes. Fairness might be about individual behaviour (the former) or about the structure of society (the latter). Wealth taxation is a microcosm of broader political arguments about the importance of individual agency versus societal structure. But in the UK - and likely elsewhere - the former argument has substantially more purchase. That’s why it so hard to tax wealth.

Types of Taxes

Speaking of fairness, we also asked a question that YouGov had run before, about ‘how fair or unfair’ people thought various types of taxes were. We gave five options from Very Unfair to Very Fair but as before I split them into a binary variable, where ‘Fair’ and ‘Very Fair’ are coded as one and the other three options as zero.

The overall picture of ‘fairness’ across different types of taxes is hardly encouraging for proponents of taxing wealth. The three taxes with the lowest level of perceived fairness were inheritance tax, tax on interest, and stamp duty. In each case only around twenty percent of people thought they were fair. By contrast NI is viewed as fair by sixty percent and income tax is number two at fifty percent. Of slightly more encouragement for wealth tax fans, capital gains and dividends taxes have decent support in terms of ‘fairness’. We’ll come back to this.

The partisan splits are interesting. There are pretty consistent views of the fairness of income taxes across voters for the major parties. But for inheritance taxes we do see some differences. Conservative and Brexit Party voters were much less likely to view inheritance taxes as fair than Labour, Green, and SNP voters. But here’s the deal, EVERYONE likes inheritance taxes much less than income taxes.

We can do this for all the taxes, if you are willing to squint. What we see is that Labour voters not only dislike inheritance taxation. They are also not fans of stamp duty or taxation of interest. They are a bit more excited about taxing dividends than Conservatives but it’s not dramatic. In other words, to the degree that there are partisan differences in views about different taxes in the UK, they tend to be more about overall level (see the Brexit Party vs Greens or SNP) rather than the mix. And even though left-wing voters like actual wealth taxes more than Conservatives, they don’t especially like them either.

Some Paths Forward

OK, so don’t tax houses or interest. Got it. But that doesn’t take away Britain’s high wealth inequality and the fact that taxes on income are reaching historically high levels to pay for the rising demands an ageing population make on the welfare state. And it’s also true that those most aged in the ageing population do have most of the wealth. So, what, if anything, can we do?

In the survey we explored a few ideas that seem to me to be more promising ways of garnering support for wealth taxation if that’s something that you (a proud member of the 35.8%) want to do.

One possibility is a version of the types of ‘net wealth tax’ that have been batted around American politics for the last few years. Now those were targeted at millionaires and billionaires and I’m not dumb - I know anyone asked in a survey if they want to tax millionaires and billionaires will say ‘where do I sign?’

So we asked a slightly vaguer question: ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “There should be an annual tax on the net wealth of the wealthiest households in the UK.” (By net wealth, we mean the total value of houses, stocks, savings, and other wealth).’ We have a five point scale, which once more I convert to one for ‘Strongly Agree’ or ‘Agree’ and zero otherwise.

This kind of tax - on the wealthiest - is MUCH more popular than actually existing taxes. 56.3% of people agree with the statement that we should have net wealth tax on the wealthiest. The facts that (a) this tax doesn’t exist and (b) no-one ever thinks they are the wealthiest, should give us caution. Still, we’ve found a potential candidate.

Who likes it most? Well here we do see partisan differences. Labour, SNP and Plaid voters love it. Conservatives don’t.

By demographics, we see that older people are generally less excited about a net wealth tax, though not uniformly against. Education doesn’t matter at all. But with housing wealth and income we see a very sharp drop off in support among ‘the wealthiest’ - those with the most expensive houses or highest household incomes. I think they can tell who ‘the wealthiest’ might target…

The other type of wealth taxation we find some support for in our surveys is taxing capital gains more - specifically, at the same rate as income. We asked: ‘To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement: “Realized capital gains should be taxed at the same rate as income in the UK.” (By realized capital gains, we mean profits from selling stocks and other assets, and other wealth.’ And we do the same as above creating a binary variable for agreement with the statement.

Here we get really high net support - 62.2%. And while there are partisan differences as before, they are smaller. Indeed, fifty percent of Conservatives agree with the statement.

In terms of demographics - we see fewer differences, except an interesting one. People with higher levels of educational qualifications are more positive towards equalising rates. My suspicion in this case is that the more highly educated were more likely to answer or to be able to interpret the question. Which does raise some risks with using this as a key part of any policy platform.

So You Wanna Tax Inheritances?

We have found some ways of taxing wealth that might be more popular. But what about existing taxes? Is there anything we could do to create more support for what we already have on the books?

I noted above that people have cogent, well-developed arguments against taxing wealth - specifically the emphasis on double taxation. That I think is the core reason that it’s hard to raise taxes in an era of high wealth inequality. There is a moral logic to retaining wealth that is deeply embedded in the way people think about the world.

So perhaps framing matters? In a paper that my WEALTHPOL coauthors and I have produced looking at inheritance taxes in particular (you can read it here), we looked at whether exposing people to information about the very unequal distribution of house prices across the country affected their views about inheritance tax. It didn't. Information doesn’t matter either because people already know or because seeing the level of inequality in abstract terms doesn’t drive behaviour.

To extend our analysis, in a new version of the paper (which we’ll upload soon!) we tried out different framings of the inheritance tax question. We asked people if they the level of inheritance tax was too high. We did so with a series of different types of inheritance tax: the overall level, the tax ‘you’ might pay, the tax ‘your heirs’ might pay, the tax on inheritances under £325k (spoiler, there is no inheritance tax on such bequests!), the tax on inheritances between £325k and £1 million, and the tax on inheritances over a million. The scales are set up so that ‘higher’ answers mean you think the tax is ‘too high’.

We asked the question in four different ways, randomly dividing the respondents into four groups.

First, we had a baseline prompt: “Regarding the level of inheritance tax people pay in United Kingdom, do you think the level is too low, too high, or about right?”.

Second, we emphasised the double taxation frame before we ask the question above: “The inheritance tax is sometimes viewed as a ‘death tax’ or ‘double taxation’ because it taxes money again that was already taxed when it was originally earned”

Third, we emphasised intergenerational fairness: “People who receive an inheritance gain an advantage in life. Taxing inheritances can contribute to levelling the playing field, ensuring that people with similar abilities and levels of effort face similar prospects in life.”

And finally, we emphasised the potential financial benefits to everyone else of taxing inheritances: “Taxes on inheritances contribute to government revenues. By raising inheritance taxes, the government could lower income taxes or increase investments in vital infrastructure such as the NHS, schools, elderly care, and roads and railways.”

What we learned was that framing works. Emphasising double taxation pushes people to become about ten percent points more likely to think inheritances taxes are too high compared to the baseline group. By contrast, emphasising the benefits of lower income taxes and higher public spending led to a decline of just under ten percent points in people thinking inheritance taxes were too high. Societal fairness, on the other hand, doesn’t matter.

This has some quite interesting implications. The moral arguments for lower inheritance tax are much stronger than the moral arguments against it, at least in this experiment. If you want people to support high inheritance taxes you need to get material, not moral. Promising people lower taxes elsewhere or higher public spending - that’s the ticket.

And ultimately that’s why wealth taxation is hard. People don’t want to do it because they don’t believe in it. They don’t think it’s fair. They might be willing to tax the ‘very wealthiest’ or to consider treating capital gains like income as fairer. But when it comes to taxing property or savings, there’s relatively little public support because it gnaws away at many people’s fundamental views of desert, effort, and prudence. There is a reason that successful centre-left politicians such as Blair and Brown, Clinton and Obama, have appealed to these cautious, ‘petty bourgeois’ principles - they are widely held and meaningful to people.

So a word or two of caution for the think tanks, policymakers, and commentators attracted to a wealth tax. Land value taxation and wealth taxation may be more efficient, they may capture unearned rents, they may prevent overbearing power of millionaires and billionaires. All those things may be true. But people think about fairness just as much, probably more, at an individual level as at a societal level.

Invoking the spirit of Henry George and imagining a new era of pamphleting about a single land tax may fundamentally misunderstand how the average voter feels about wealth. They don’t like taxing it that much. The Patriotic Millionaires might have to attend Davos quite a few more times to see their taxes go up.

I always thought of the wealth tax as more of a service charge. Private property is a major government service. Private property, at a minimum, requires a military, a police force, a court system, and a registry system. It needs to be prepared to deal with threats to ownership, domestic and foreign, that have to be met with physical force. It needs a system to keep track of who owns what and a means of resolving disputes between parties. There are other government services as well, but the thing is that the more wealth one has, the more one benefits. Insurance companies know this. They charge more to insure property based on its value.

Most of the wealth we are talking about is government issued money, government allocated land, shares in government chartered collectives and the like. Only a small portion of it is in expensive physical artifacts. Once one stops thinking of it as a tax but rather a service charge, it makes a lot more sense. Income taxes and the like approximate a wealth tax by assuming that the value of an item is in its ability to produce income whether by sale, lease, operation or otherwise.

Very interesting and enlightening read. Thank you!

How do you think a wealth tax that excludes a primary residency, combined with a £500k personal allowance (so first £500k of net wealth outside the family home would be taxed at zero), would be perceived by UK voters? Given 96% of UK housing is a primary residency that would obviously only require the government to value 4% of housing a year for tax purposes.