I have a cursed professorial title. I’m Professor of Comparative Democratic Institutions at Oxford. That’s long. Too long to write, too long to say out loud without a sip of water. In classic Oxford style it reflects the fact that I applied for two jobs - a professorship in Comparative Political Institutions, and another in Democratisation, and when they couldn’t figure out who to give the jobs to, they essentially merged the positions and hence my elaborate title.

But the title does give me one boon - I feel like I am in a strong position to make claims about, well, ‘comparative democratic institutions’. For example, whether Britain currently is, and will be post-election, a ‘democracy’.

As opposed to what you may ask? Ah, my non-Telegraph reading friend, a ‘dictatorship’ of course! The Telegraph columnist Tim Stanley recently penned a column bemoaning how Britain’s First Past the Post (FPTP) electoral system doomed the Conservative Party and hence will ‘create a dictatorship’. You might think I am misquoting. I understand your skepticism. Surely no major broadsheet newspaper would write such a thing. Uh huh… here’s the quote

So I have to say, I do agree with the first clause - it is indeed true that FPTP was never meant to create a dictatorship. Tim and I are on the same page. The bit after the hyphen, though. That is… well, I believe the technical term is ‘nonsense’.

So why is Tim Stanley making this claim? Let’s assume good faith. Perhaps this is a general claim about how decisions are made in Britain’s rather unconstrained Parliament.

In a way, I think Lord Hailsham is to blame for coming up with the famous phrase ‘elective dictatorship’. This was meant to convey that between elections, there are few limits on a British government. Parliament is sovereign. This is the A V Dicey view - parliament can make any law, save for one that binds its successors (because the successors of course can also operate with minimal constraints).

There are some wrinkles - because it was the Treaty of Union between England and Scotland that established the modern UK, there are some pre-existing Scottish laws that cannot be altered. Similarly, many people argued that while Britain was a member of the European Union, Parliament faced real limits on its legislative capacities. The various referendums of 2014 and 2016 mean that the former is still true, the latter very much not. There is also the case of the Human Rights Act and whether this supersedes Parliament’s rights to legislate. So it’s complex.

But the basic gist is that Parliament is indeed fairly unfettered in its ability to legislate.

Here's the crux, though. That is always true if you command a majority in Parliament. It does not matter how big that majority is. Parliament’s decisions are made by majority vote - that is how laws change. Scraping through or land-sliding - doesn’t matter.

And the weird thing is this is exactly what Tim Stanley says straight afterwards - our legislative system does permit quite unfettered lawmaking. And it did for the Tories, when they passed Brexit, apparently. So, wait, was that also a dictatorship? Have we always been living in one? Are we the baddies?

After this, then we have a tonal shift - “a Left-wing government with barely any opposition” (I presume parliamentary opposition, because it feels to me like there will be some quite vocal opposition from entities such as, oh I don’t know, the Daily Telegraph).

That opposition is impotent though is a standard problem with the British system. We don’t have supermajority rules (see last week’s post) that give the opposition power to block things they don’t like if they can command forty percent of the vote, or a third, or some such. In fact, the opposition don’t get much at all - a few questions at PMQs, seventeen-odd ‘opposition days’ to set the parliamentary agenda (but not pass bills), seats on House of Commons select committees, and the right to party political broadcasts at various points. And that’s more or less it.

What the opposition never has in the UK is much ability to block policy, let alone create it. It’s unpleasant being in opposition, I get it.

But that doesn’t make Britain a dictatorship. Because if a big Starmer victory makes it a dictatorship then surely that was true in past such moments over the last century. You see, there were also landslides in the past. In 1931, Stanley Baldwin’s Conservative Party won 470 seats as part of a National coalition with Ramsey McDonald’s National Labour on 13 and TWO breakaway parts of the Liberal party as part of the National coalition with 68 seats between them. Wild days. That meant the National government had 554 seats. This left Labour as the official opposition on 52 seats.

So, did Britain suddenly become a dictatorship? This was clearly a challenging time in global and British politics, at the bottom of the Great Depression. But nothing fundamental changed formally. Let me demonstrate.

Because democracy is a contested concept, political scientists have developed a wide array of indicators for it. Some are minimalist - is the executive elected by a (near)-universal franchise and are elections competitive? This is basically the definition first stated by the economist Joseph Schumpeter - democracies are where “individuals acquire the power to decide by means of a competitive struggle for the people’s vote”. In other words, do you have competitive elections, which matter in terms of actually electing the person who makes decisions, and is it the people who get to vote?

It’s hard for me to come up with a world in which either 1931 or 2024 violate these dictates. We have lots of parties competing fairly in an election for the vote of the general public and whoever wins, assuming they win a parliamentary majority, gets to make decisions.

For the life of me, I can’t see how this changes just because Labour win a lot of seats. Now we could argue I suppose that because FPTP ‘creates’ majorities by turning a large plurality of votes into a huge majority of seats that the people’s vote imperfectly translates into power. But that doesn’t violate our simple definition - there was, after all, a competitive struggle for the people’s vote.

Generalissimo Starmer is only going to change this in the future if he prevents elections from being competitive (by suppressing the vote or banning parties), or if he engages in an auto-golpe - a self-coup a la Alberto Fujimori in Peru, where he decides that he can continue to make decisions without future elections. All things are, I suppose, possible in the multiverse. But…

For good measure, here is what the minimalist history of UK democracy looks like, where we define ‘the people’ as both men and women - and hence female suffrage in 1918 is our core moment. (I’m a stickler, so I would prefer 1928, when women acquire the right to vote at the same age as men but OK). This is data taken from the Our World in Data website using Carles Boix’s binary measure.

This is the most boring graph I have ever put online. Britain’s a not a proper democracy until 1918. Then it is. It’s like a TLDR version of Whiggish history. But what don’t you see? Anything happening in 1931. Or really any point after. Because nothing that seriously affected the core Schumpeterian principles of democracy changed.

Lest you think all countries’ graphs look like this, they don’t. Here, for example, is Argentina.

And here is Turkey.

The British democratic experience since the end of the First World War has been delightfully dull compared to elsewhere. Perhaps that’s one reason why columnists who should know better throw the word ‘dictatorship’ around. Because they don’t, have never, and never will live in one. So they can blithely make blood-curdling claims that demean the actual experience of much of the world’s population. They have become spoiled by stability.

But maybe you find this kind of minimalist take on democracy unsatisfying. Boy do I have a never-ending series of political science articles to recommend to you. But the most developed response to the minimal, formal institutional view of democracy comes from the scholars running the V-DEM project, which uses expert opinions on a whole array of sub-components of democracy.

Here is what the UK looks like for five of their different measures, again using Our World in Data’s excellent website. Each of these picks up slightly different desiderata - so electoral democracy is about formal voting rules, liberal democracy adds freedoms of press and courts etc, deliberative democracy adds some indicators about public voice, egalitarian democracy about social or economic rights or equality (IMO this is an outcome of democracy not a definition but, as I said, I am a boring stickler), and participatory democracy that emphasises things like turnout and referendums.

These lines are smoother than the minimalist version, that’s for sure. And there is some interesting variation - Britain does less ‘well’ on participatory democracy because it has fewer meaningful subnational elections or direct democracy channels than other countries.

But the main story is of a stable and slow rise with a big jump in you guessed it, 1918, a small decline in some indices in 1939 during the war, and another jump afterwards as plural voting was removed.

There has been some bobbing and weaving over the past two or three decades. Some of it is a jump up around the time of devolution. And there is a bit of downward coding in last few years, some I strongly disagree with around the time of Brexit (something about factionalism, which I think this is BS), and some around the time of the prorogation and then the lockdowns, which seems fairer. But this is all super marginal stuff.

So what’s the story here? No declines in democracy during super-majorities and really minimal change overall except around big reforms, usually with the title Representation of the People Act. There is no real evidence of democratic ‘backsliding’ in Britain.

And I think this is really important to get our heads around. Many people on the left acted as if the Boris Johnson government was inches away from declaring a dictatorship. There was lots of panicked writing about prorogation and the use of Henry VIII laws.

But in my view, though I understand the concerns, this was a legitimate debate about the relative powers that the British executive (essentially the PM and Cabinet) should have vis-à-vis the legislature as a whole. Personally, I’m a fan of more checks and balances and so I would rather give the courts or the Commons more powers to restrain the government than fewer. But I do think this is a debate that is occurring within democratic boundaries, and fair-minded people can disagree, as I do for example with Richard Johnson and Yuan Yi-Zhu and their excellent book.

Which brings us back to electoral systems. Like <checks notes> Tim Stanley (?!?), I would prefer a proportional electoral system to our FPTP one. I think that our current system does produce highly disproportionate outcomes, as John Burn-Murdoch’s excellent piece in the FT shows.

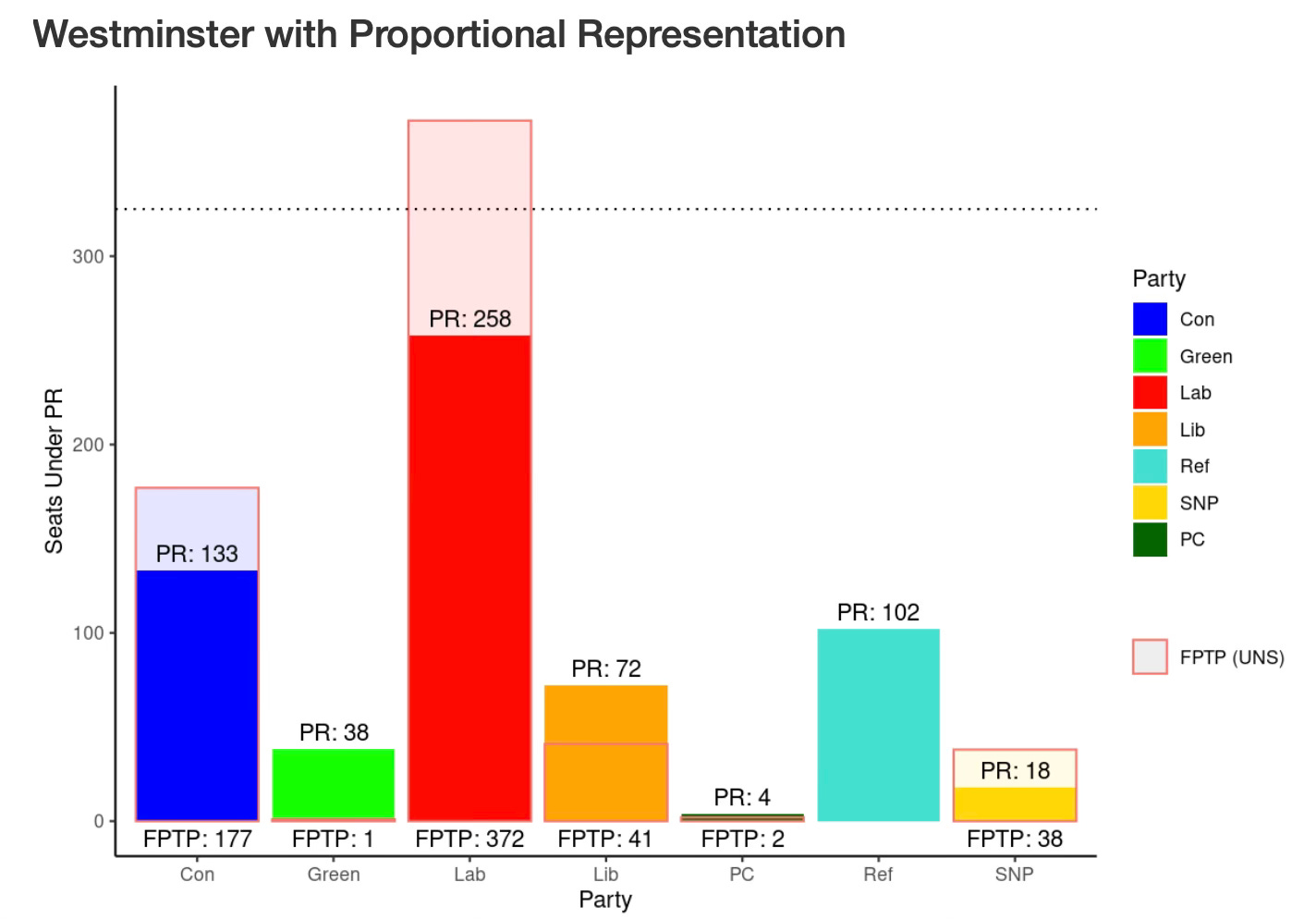

Indeed because I have an app for everything (or more precisely, an app that does everything), you can see just how different the Commons would look under PR vis-a-vis FPTP on current polling averages (which I take from Election Maps’ nowcast).

You can see the enormous unfairness of our system here, even on a rather milquetoast Uniform National Swing projection for FPTP. Labour on course for a huge majority, not because they will have far more seats than the Conservatives won in 2019 (and indeed, Labour’s current polling average is well below the 45% Boris Johnson won), but because of the collapse of the Conservative Party.

That collapse in vote share is heading largely to Reform (and of course some to Labour and the Lib Dems) but third parties do terribly in our system. My model doesn’t even have Reform picking up any seats but that’s because it is based on last election’s results, where the Brexit Party refrained from running in lots of seats, including Clacton, where Nigel Farage is almost certain to win. I suspect Reform will win seats in the mid single digits. Under PR they could have low three digits. The Greens also are massively disfavoured by FPTP and the Lib Dems somewhat so, with the SNP and their regionally concentrated vote, beneficiaries of our current system.

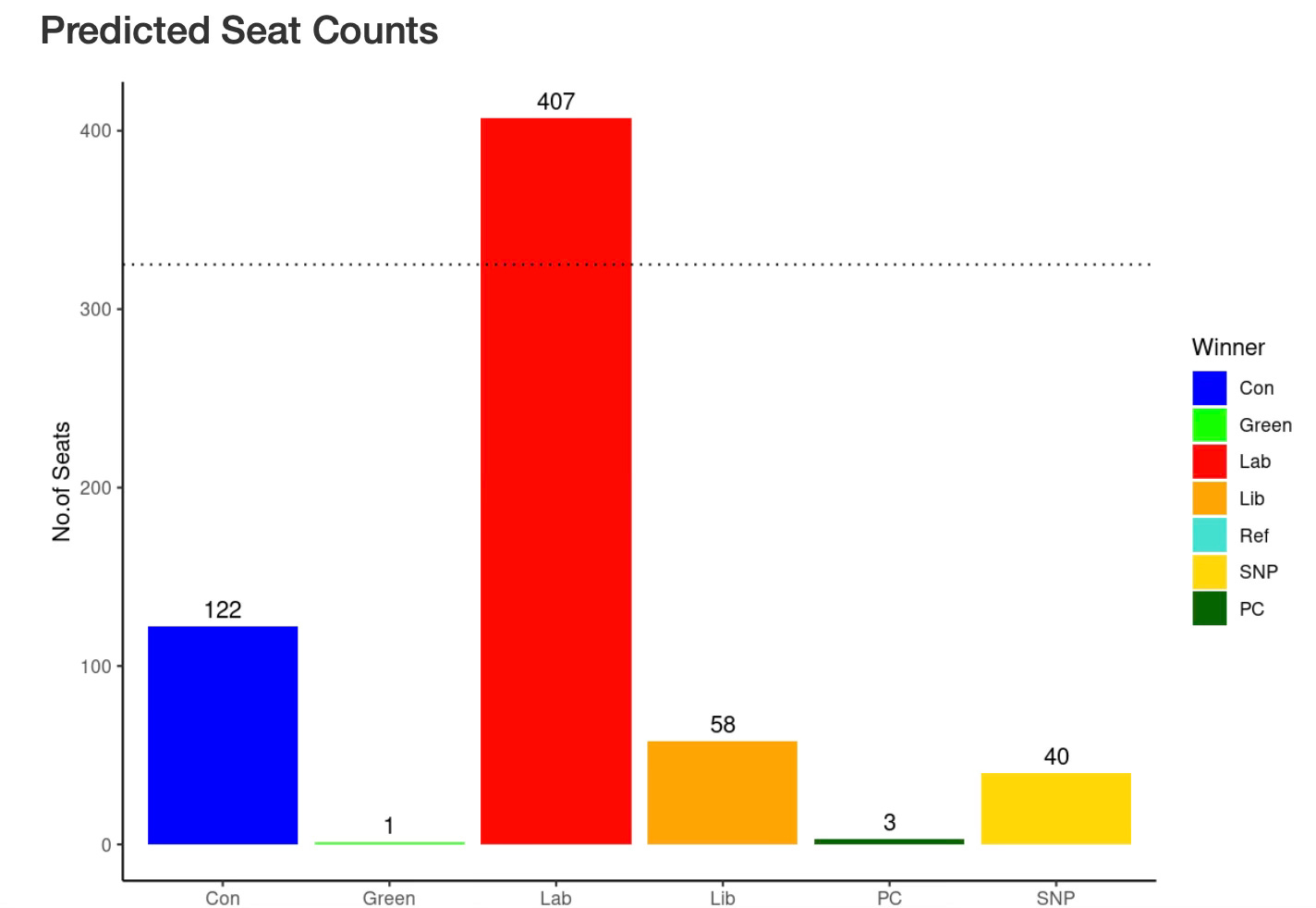

Here by the way, is the even more disproportionate FPTP outcome that we will get on current polling if the swing away from the Conservatives is proportionate rather than uniform (i.e. if Conservatives go down from 45 to 22.5 percent, then instead of substracting 22.5% from their vote share last time in each constituency (UNS), we halve the expected vote share from last time in each constituency (Proportionate Swing)). The Conservatives lose another fifty seats and it is a landslide larger than any since the war.

Other prediction websites give more extreme outcomes. Ones that look like our old friend 1931. But my model is more moderate and also has the benefit of actually having its code available so you can see what I’m doing.

Is this the sign of a healthy electoral system? Not really? Is it undemocratic? No.

This is not hard. There is more-or-less completely free competition for the people’s vote and the legislature is directly produced by that and in turn empowers the executive that acquires ‘the right to decide’. There is no chicanery. It’s just how we turn votes into seats.

And PR is not necessarily more ‘democratic’ even with a much wider or more expansive of what ‘democracy’ means. For example, in PR, the governing party almost always has to govern in coalition with other parties. Which means that there isn’t really a true ‘governing party’ - it by definition cannot make decisions on its own if it relies on other parties in its coalition for a majority in the legislature. Essentially, there are many actors who have acquired ‘the right to decide’ because if they threaten to leave the coalition that can bring down the government.

This means that accountability is hard in PR systems. Who do you blame if you don’t like a government decision? All of the parties in the coalition? The lead one? The one controlling the ministry that made the decision? Another party who you suspect derailed better decisions? <shrug emoji>

Political scientists refer to this as the clarity of responsibility and it’s lower the more veto points you have - be they other parties in a coalition, or other Houses of Parliament, or independent agencies such as central banks. The Westminster system, for all its flaws, does provide clarity of responsibility - as the Conservative Party to their great despair are finding out. We are having an ‘accountability moment’.

I would love it if we could just have arguments about our electoral system and its merits without hysterics - without calling a perfectly legitimate, if disproportionate, result dictatorial.

But I suspect the reason such articles are being written is because the shoe is on the other foot. The Conservatives will do badly from our electoral system on this occasion so suddenly it’s so unfair it’s dictatorial. Was the same system dictatorial in December 2019? Of course not old chum. No, that was fine because… reasons…

We all have, I suppose, lines to take dictated by our jobs. Telegraph columnists are not feted usually for their astutely and ascetically neutral take on political matters. Fair enough.

But the advantage of my insanely long professorial title is that I do feel qualified to try and set the record straight. The next election may produce an outcome that is undesirable - either because you are a Conservative and you are looking down the barrel of being out of office for several years, or perhaps because you find the disproportionate outcomes associated with FPTP to be distasteful.

The outcome may be undesirable - sure - but it is emphatically not undemocratic. And it demeans both public debate in the UK and the lives of the billions of people who still live in dictatorships, to pretend otherwise.

If you got this far, you probably really like debates about democracy. Then boy are you in luck that I have a podcast series with Tortoise, called What’s Wrong With Democracy? And this week, I spoke with Lone Sørensen, Associate Professor of Political Communications at the University of Leeds, about how populists use disruptive language and theatre to win elections, and with Kevin Casas, the Secretary General of IDEA and ex Vice President of Costa Rica about what happens when populists actually win elections. Listen here or here. Go on, do it!

I found this article really helpful in its framing of the arguments between FPTP and PR, but in common with most analyses, it does not define PR. Is it possible/realistic to shown a comparison between the various forms of PR and FPTP and how each performs in relation to the issues that you describe?

I think a wise Keir Starmer would introduce PR for local government in England and Wales first (like STV used in Scotland and NI). Then, once bedded in, offer it for Westminster. We probably wouldn’t then need a second chamber, as policy would be more consensus driven. If need be, we could have a smaller fully appointed second chamber nominated by the devolved nations and regions.