Deluded by a Common Language

The UK General Election is in danger of North America-brain

Once upon a time you could just blame The West Wing. Generations of British centre-left politicians, think-tankers and journalists grew up in the thrall of President Jed Bartlet, the gruff but kind Nobel-prize winning economics professor turned most powerful man in the world. Bartlet could win over voters (maybe) and viewers (definitely) through a mix of moral suasion, good faith arguments, and the sheer power of academic wonkery. This, to a certain type of UK politico, is what American - and hence British - politics should be like.

Strangely, the uber-wonk has not become a staple of contemporary politics. How can this be, cry a million university professors in unison. Why don’t the public understand? But if anything, political leadership has become less wonky, more populist, more erratic, more pandering. Less Bartlet. Maybe there aren’t many Bartlets out there. Or maybe Bartletery doesn’t really compel people politically.

There are some proto-Bartlets out there but they have had negligible success - most obviously Michael Ignatieff with the Liberal Party of Canada, a famous academic whose skillset did not translate smoothly into electoral politics. I think the closest we ever got to a successful Bartlet was Barack Obama - but his professorial tone was not I think core to his charisma, and his good faith debates with Republicans generally produced effective obstruction rather than persuasion. In other words, Bartlet was one of the less important parts of the Obama phenomenon.

In British politics, to differing degrees Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband had some of the West Wing wonkery about them. But actual Prime Ministers: Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Theresa May, Boris Johnson, Liz Truss, Rishi Sunak; not a Bartlet among them. Except sort of if you squint, Rishi Sunak - and well that’s not going brilliantly.

Despite the popularity of The West Wing - I don’t think it translated well to British politics. And its day is done - a relic of the naughties (like so many themes of this Substack it seems). But it has been replaced by new American influences. And, in my view - despite my own lengthy period of studying and working in the States - these aren’t landing all that much better.

Over the course of the General Election campaign - all three weeks of it - we have seen a number of American politics terms creep into British election discourse. The two most prominent have been ‘gerrymander’ and ‘supermajority’. For reasons I’ll come to, I don’t think either of these words is useful in the British context. But they are also a symptom of a bigger disease - the influence of US political social media on British politics, especially on the right.

OK so what’s the problem with these words? Let’s begin with the less harmful example. ‘Gerrymandering’ has been used by Conservatives to refer to Labour giving votes to sixteen and seventeen year olds, which horror of horrors, they might be doing for instrumental political reasons. Contrasted to the ascetic, morally pure politics of the last decade I suppose.

The Telegraph recently had a piece by Will Hazell, their political correspondent, talking about Conservative complaints of “gerrymandering”. I’m not sure who these unidentified Conservatives are. But the Telegraph has previous. In 2019, Tom Welsh, now comment editor at the Telegraph and whose opus includes a series of paeans bridging the vast ideological chasm between Elon Musk and Ayn Rand - wrote a piece titled “Giving 16 and 17-year-olds the vote would be egregiously cynical gerrymandering”. So perhaps Will just walked upstairs for a quote.

In any case, this is not a great use of the term ‘gerrymandering’ - what the term refers to is the drawing of geographical districts that favour particular demographics and hence political parties. The image of the top of this post is that rare thing: a famous political science cartoon. It reflects dissatisfaction with the politicised drawing of Massachusetts Senate districts in the early nineteenth century. The Governor accused of such chicanery was Eldridge Gerry and - stay with me - some of the new districts looked like a salamander. Hence ‘gerrymander’.

Now you absolutely could do this in the UK given we have geographically defined constituencies with borders that could be and are moved about. But… we have a politically neutral Boundary Commission that does this, usually to cross-party satisfaction.

Enfranchising sixteen and seventeen year olds is a contentious and debatable proposition. I can see both sides of the argument (don’t snitch on me to Phil Cowley). But it doesn’t involve geographic boundary drawing. I mean I suppose it could if we started drawing electorally boundaries to sneakily incorporate sixth-form colleges and then forced students to live in them permanently. And perhaps that is the next stage of the Daily Telegraph approved national service plan that the Conservatives have concocted. But I’d imagine not.

Basically, this is an example of people using a word that they don’t really understand to mean something different than it does. It’s true that gerrymandering as a phrase is used outside the US - in particular, in Northern Irish politics. But again that was because of how geographic boundaries were drawn. Its current use is just dumb.

But perhaps harmless. Because we all get what the Daily Telegraph and its Conservative sources are trying to say - they think the change in voting rules advantages a particular party. Fair enough. It probably does and it’s totally appropriate to oppose that. Just as Voter ID seemed to bias towards Conservative constituencies. We can argue the merits of Voter ID as a policy AND note it has a partisan bias. Just as we can with votes for teens.

The more dangerous - for political thinking - misuse of an American concept is the term ‘supermajority’ which has been blasted across the Conservative-leaning press over the past few days. Defence Minister Grant Shapps was one of the key points of origin for the supermajority discourse but it has spread far and wide. The idea seems to be that if Conservative voters abandon the party for the temptations of Reform UK (or indeed the Liberal Democrats, who Conservative strategists appear to be hoping don’t actually exist), this will produce a Parliament where Keir Starmer has a ‘supermajority’.

This appears to confuse the concept of a ‘supermajority’ with a very big majority. And all you need in the House of Commons is a simple majority. Doesn’t matter how big. You can win or lose votes by one vote - just ask Jim Callaghan, who lost a vote of no confidence by a single vote.

Now, it is obviously easier to avoid that kind of terrible outcome if you have a very big majority. And similarly with a very big majority it is simpler to pass controversial or unpopular bills. If your parliamentary whips have any skill at all at herding the cats of Westminster, you are going to be able to pass most bills with a decent working majority of a few dozen. But it very much doesn’t guarantee that your party will all sing from same hymn sheet. Think about the collapse of discipline in the Conservative Party of the last five years, who entered office with a very sizeable majority and spent it on internecine fights, baroque scandals, and rather minimal achievements beyond Getting Brexit Done.

A ‘supermajority’ used correctly refers to the case when things cannot be passed without crossing a threshold some way north of a simple majority. In American politics this includes things like the de facto supermajority of sixty votes in the US Senate thanks to the filibuster. Or for a constitutional amendment - two thirds of both the US House and Senate and then three-quarters of the states. Now those are some pretty high hurdles.

But the House of Commons (save for the brief era of FTPA, where a 2/3 vote could approve an election) operates on a much simpler basis of simple majorities. Keir Starmer isn’t going to get much more bang for his buck if his majority expands from 50 to 100 to 150. Indeed, he may find a very large majority stores up internal troubles in the party since nearly half of his MPs can go rogue with minimal consequences.

And while I get what Shapps and others are trying to say I fear this reflects a basic problem for conservatives in the UK, which is that they are soon going to be in a world where they would really hope to have the kinds of checks and balances that other countries with actual supermajority rules have.

This is a complicated form of copium - it doesn’t help the Conservatives that much if Labour have 350 seats in Parliament vs 400 vs 450. They are not going to have any power to do anything they want to do. That’s what happens when you lose an election in Britain. Supermajorities in America protect losing parties - especially in the Senate. There are no such protections for the Conservatives, they are going to face the harsh winds of political isolation.

And it leads to Conservatives making elementary mathematical mistakes as can be seen in this Telegraph oped by ex Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick.

Looking past the ‘one-party state’ hyperbole (it’s hardly a one-party dictatorship like the CCP in China if it’s democratically elected), the bigger problem I have is the idea that there is a ‘Right-wing common sense majority’. There isn’t. That’s the problem. Conservative plus Reform votes are well under 40% in the polling. Combined they are typically well under Labour’s predicted vote share, without adding the votes that go to other ‘progressive’ parties such as the Greens, Lib Dems, and (if you squint) the nationalist parties. By harping on about super-majorities, the Conservatives are forgetting that they don’t even seem to be able to assemble a simple majority, even if they win back all the votes they have lost to their right.

So where are these largely unhelpful and sometimes harmful terms coming from? I think part of the answer is that the right in the UK has become America-brained in a similar way to centrist dads in the West Wing era.

This can most easily be seen among British who have had some success in America - be they Douglas Murray or Niall Ferguson. In their case it’s not enormously surprising to see them write opeds for British newspapers that seem unusually focused on American campus politics. More surprising is how obsessed British-based conservatives became with saga of say Claudine Gay, erstwhile President of Harvard University, or with pro-Gaza encampments at Emory or Washington Universities, locations I predict very few British journalists could accurately identify on a map. (OK I am advantaged here by studying and teaching in US universities for over a dozen years, but also you don’t see me constantly comparing British politics to student activists at Yale).

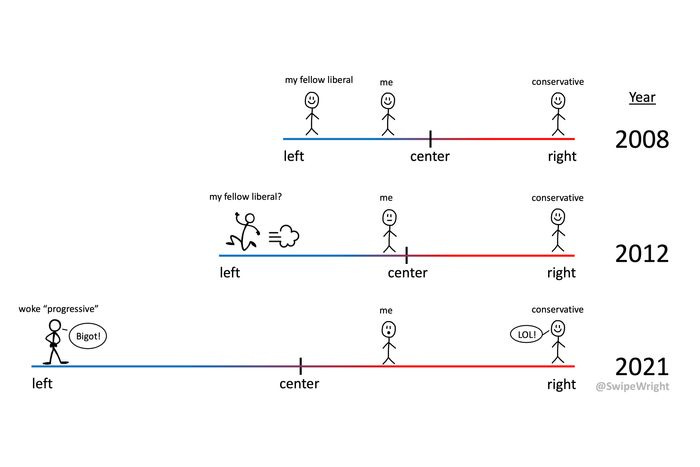

Matthew Goodwin, British political scientist and possible political party founder, recently tweeted a cartoon that was a version of one originally tweeted by Elon Musk, which I copy below.

First off, I for one am excited that a political scientist believes that Labour in the 1980s were similarly left-wing to Labour in the 1990s. It’s a unique re-analysis of Michael Foot and Neil Kinnock that is bound to be a bestseller in the field of counterfactual history. Second, Matt is a little younger than me, and I was born in 1977. My first political memory is the Berlin Wall falling. But perhaps he was a centrist toddler. Who’s to say? Finally, I know David Cameron hugged a hoodie and got interested in ‘green crap’ (as he called it) for a few minutes but I don’t recall Labour and the Conservatives being indistinguishably far left a decade ago.

No I think what’s going on, is that Matt took the Elon Musk approved cartoon drawn by Colin Wright (below) and ran with it. Now maybe the Wright cartoon makes intuitive sense to some Americans offended by ‘woke’ and who have moved from voting for Obama to supporting Trump. This is a large set of people. There is a grand debate among political scientists about polarisation over the past few decades. And the general view is that both parties have moved from the centre but that it’s actually been more pronounced on the right. But as people age they do tend to become more socially conservative so I can see how this initial tweet has appeal. It just doesn’t translate brilliantly to Labour and the Conservatives since the 1980s.

I know Matt is joking. And it’s hardly the end of the world. But it’s all a bit odd and only makes sense if like me you are very online and know the American meme to which he is referring and are then willing to make another series of mental jumps about exactly what the Conservatives and Labour have been up to.

In line with this, there has been a shift among right-leaning folk in the UK, including Conservative MPs, to excitement about the Trump-era Republican Party. The British public remain resolutely opposed to Trump - he has a 71% disapproval score. It’s not like Biden is super-popular, his disapproval in the UK is 43%. But the idea that there is an underlying ‘common-sense majority’ for Trump in the UK is balderdash.

And yet Liz Truss, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees Mogg and others have been banging the Trump drum for years. Maybe this is politically smart - Trump is quite likely to win the next election - but I suspect it is more because they actually just agree with Trump ideologically, not least because they have absorbed so much online US content.

Think about the weird Ron De Santis boomlet in the UK press. For a time, a year or so ago, The Times and The Telegraph were constantly running puff pieces about the Florida Governor, and then lead candidate for the Republican Party nomination for President. But who in Britain is that excited about the idea of punishing theme parks for protesting anti-gay laws, or creating new anti-woke campuses and syllabi (as with what happened to New College in Florida), or with banning abortion, or with banning lab-grown meat, or whatever new thing De Santis has come up with? I’ll answer that question for you - a few Telegraph columnists who spend too much time online.

Now the British left are not immune from America-brain. Defund the Police and ACAB crossed the Atlantic. The Democratic Socialists of America have their connections here. Obviously some of the Gaza encampments on UK campuses have followed tactics developed by their US equivalents. But in a post Jeremy Corbyn world that has not fed over into the current Labour Party.

It’s true that Bidenomics and the Green New Deal have had more effect in the mainstream party - the former in Rachel Reeves’ ‘securonomics’ and the latter in Ed Miliband’s climate plan. And Labour will need to be careful not to mistake Britain’s industrial prowess and ability to get away with loose fiscal policy with that which prevails in America. The dollar truly does provide America with ‘exorbitant privilege’ in fiscal and monetary matters that other countries lack. But these are policy similarities not meme-based too-online stuff. When Labour spends all of its time producing cartoons of Keir Starmer with lasers coming out of his eyes, then I’ll complain.

There’s one final form of America-brain, or should I say North America-brain, that I think pervades the current campaign and that’s the Canada analogy. As most readers of this wonky politics blog will know, in 1993 the Canadian Progressive Conservative Party managed to collapse from a majority to just two seats under PM Kim Campbell. They had lost much of their vote to the Reform Party (sound familiar?) who outflanked them to the right.

As comparisons go it does feel fairly on the nose. But but but... there is a big difference between the Canadian Reform Party of Preston Manning and Nigel Farage’s Reform UK.

Manning’s party had a clear geographic base in the western resource-rich Canadian provinces, especially Alberta. Canada often appears to violate ‘Duverger’s Law’ - that FPTP leads to two parties, since votes for third parties get wasted. But of course Duverger isn’t wrong - it is a theory about each constituency not the national level. So regional parties can do very well in FPTP - as the SNP show in the UK and the Bloc Quebecois have often shown in Canada. And Reform were a party of the West so were able to be the de facto opposition to the Liberal Party everywhere west of Ontario. So they won 52 seats, largely in Alberta and British Columbia.

Eventually the old Progressive Conservative Party had to merge with Reform to produce today’s Canadian Conservatives. Under sort-of populist sort-of-right-wing leader Stephen Harper, they had won back a majority by 2006.

Lots of political wags have been telling a similar story, with Nigel Farage replacing Preston Manning and Rishi Sunak cast as the unfortunate Kim Campbell. And, she rather hopes, Suella Braverman playing Stephen Harper.

But there is a big difference. Reform UK’s support is spread across the country fairly uniformly. They are unlikely to win seats in the double digits. Perhaps they could make a play for England’s Alberta - Essex? Lincolnshire? - but I suspect that will be hard to do. Outside of Scotland, Wales and NI, it is hard to sustain a regional party in the UK. Just ask the intrepid members of the Yorkshire Party.

So in my view, this type of analysis is Canada-brained. Like it’s national counterpart, cooler, more reasonable, more agreeable than mad online America-brained stuff. But also wrong.

All throughout writing this piece I have had to control my inner comparative politics scholar urge to shout - but we can compare countries! Politics is universal! It’s not completely idiosyncratic and best left to national experts! Yes. But also, you do have to get the concepts right.

And remember, other countries mostly aren’t sitting there looking at the UK, saying what does this tell us about our election? There are a couple of read-throughs, sure. Like don’t govern poorly for over a decade. Don’t leave a large trade zone without a plan on how to beforehand. It’s not that elections elsewhere are meaningless.

But mostly, our political challenges are our own. Twitter is not Britain, sure I agree. But American Twitter, that’s really not Britain.

Thanks for reading Political Calculus and helping me edge closer to the magic number of 5000 subscribers. I don’t know what kind of achievement I will unlock if and when that occurs but go on, help me find out. And please do listen to the latest episode of What’s Wrong With Democracy? In the most recent one I talk to Sacha Hilhorst from Common Wealth, Polly Curtis from Demos, and Richard Wike from Pew about declining trust in Britain and worldwide. There are some great stories about dog theft - go on have a listen.

No gerrymandering in the UK? Clearly you're too young to remember Westminster in the 1980s. True the Tory Party didn't shift the boundaries to suit their voters but they did it by changing politically marginal wards estates housing tenures to attract Tory voters and moving potential Labour voters to already safe wards or out of the authority altogether, The District Auditor wrote "I have found that the electoral advantage of the majority party was the driving force behind the policy of increased designated sales ... My view is that the Council was engaged in gerrymandering, which I have found is a disgraceful and improper purpose, and not a purpose for which a local authority may act." See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homes_for_votes_scandal.

Interesting as ever. But I wonder whether you have passed too easily over Gordon Brown as a 'Bartlet' - 1st in History and then a PhD in political history, and a lecturer in politics, who became a bit of an economics 'nerd' as well ("Post neoclassical endogenous growth theory", ok, Ed B. wrote it - but still). Chris Grey