Now You Have to Run the Museum...

Keir Starmer carried the Ming vase successfully to its plinth. Now he should be less cautious.

This Substack is back from holiday. As is What’s Wrong With Democracy?, where we have just begun a three part mini-series on the US Presidential Election. You can listen to the first episode on voting demographics, with Chris Towler, Kira Sanbonmatsu, and Mark Hugo Lopez, here.

Consider a comparison. Two Labour Prime Ministers. Both elected in landslides with over four hundred parliamentary seats. Both crushing the Conservative Party into a remnant of its past glory. Both buoyed up on the centre-left by a large Liberal Democrat contingent in Parliament. Both telegenic lawyers with self-styled prudent Chancellors. And.. um… that’s about it…

Tony Blair’s first one hundred days marked a sprint of legislation that fundamentally upended Britain’s constitutional order - an independent Bank of England, starting the process of devolution, banning handguns. Things could, as they say, only get better.

By contrast, Keir Stamer’s first sixty or so days, have been less dramatic. Largely, we have just seen the ending of Conservative policies such as the Rwanda scheme and the Free Speech Bill. Merits or demerits of those policies aside, that’s fine - Starmer is not a dramatic figure. But more problematically, his first sixty days have also been dour.

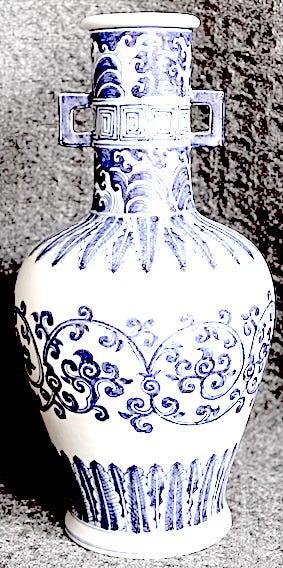

During the General Election campaign, Keir Starmer was often depicted as following a ‘Ming vase strategy’. This slightly rococo description, which feels like something someone who has watched too many Pink Panther movies would come up with, was meant to symbolise Starmer very slowly and painstakingly carrying a fragile electoral strategy to victory. One false move, one risk-acceptant moment and the whole election plan would apparently shatter into a thousand pieces on the floor. So, no sudden moves, get the vase to its plinth, and breath a sigh of relief as you become Prime Minister with a nice fat majority.

Well I guess the strategy worked. Labour does indeed have an enormous majority. Though since Labour’s ultimate vote share was rather disappointing and certainly below the polling expectations, one wonders if it worked quite as intended.

But here’s the part they don’t mention about the ‘Ming vase strategy’ - once the vase is on its plinth you have to run the actual museum. And suddenly an incredibly risk-averse strategy and the mindset it creates may not in fact be optimal.

Starmer and Rachel Reeves have been characterised as ‘securocrats’ - people who emphasise a very steady, austere, mildly authoritarian kind of leadership that frankly is quite successful with the British voting public who generally don’t like the idea of any sudden moves. So the electoral strategy of emphasising security and creating policies that appeal to the many many Brits who are socially authoritarian and quite fond of big government economic policy was likely wise.

But it has also locked the new government into a rather meagre, defensive, dare-I-say depressing vision, that I fear will work less well as a governing strategy than it did as an electoral one. In particular, Britain runs a risk of becoming caught in a doom-loop. Low economic growth means less of a boost to the Treasury in taxes, which means less public investment, which in turn holds back economic growth. A low-public investment equilibrium.

Now to be clear, not all public investment boosts growth. In particular, investing in higher pensions through a triple-lock set of increases - to name a certain recent policy - does very little to change incentives in the actual workforce, except possibly have people leave it earlier. Similarly, investing in expensive new customs buildings and staff because you decide to create large new trade barriers may be essential but is unlikely to be growth-creating.

But other investments really would help. An obvious example is better transport infrastructure - trams, trains, roads - in the North of England. Britain has far too many cities that underperform their continental rivals pound for euro because their local economies are disconnected and travel around them is hard. Investment in education might also be growth-enhancing. It’s likely over-played by some - we know that higher teacher pay, smaller class sizes, etc don’t always directly ‘pay for themselves’ (though they might be worth doing anyway). But letting continued under-funding continue, and in particular, letting universities collapse in lieu of a bailout, will almost certainly harm the growth prospects of many smaller cities.

More contentiously, low public sector salaries and poor job conditions can create new political problems. Not just in term of strikes - and it’s in this area that Labour have bitten the bullet - but also in requiring much higher levels of immigration to staff the services - witness the huge increase in health and social care visas. Obviously rising immigration is something that Conservative and Reform voters care about much more than Labour ones - but it remains a salient election issue and will almost certainly be one that the next Conservative leader campaigns on.

The problem of course with responding to all of this by raising public investment is that it is expensive and Labour have, perhaps unwisely, ruled out raising the main types of taxation governments usually rely on - income tax, national insurance, and VAT. And that produces three potential scenarios.

First, Labour simply fail to increase public investment and the country remains in its doom loop. I suspect that is what would have happened had the Conservatives won the election - not least because I don’t think their heart was really in Liz Truss’s appeal to increase growth through some pretty ‘striking’ supply-side policies.

Second, Labour find the revenues from elsewhere, albeit having abandoned increases in the main tax sources. And this means, yes, VAT on private school fees and an end to non-dom status. But bluntly, that’s peanuts. More likely it means looking at some form of wealth tax. And boy is that going to be hated. My own polling has found that wealth taxes are really not very popular - especially ones that are specific rather than vague and general. The three taxes found least ‘fair’ in my survey? Inheritance tax, stamp duty, and tax on interest.

Now there are less unpopular forms of wealth taxation - equalising capital gains rates or capping tax-free pensions contributions (a sort of future wealth tax). But these both have pretty sizeable ‘tax incidence’ effects - that is, they alter people’s behaviour in ways that we might not want - having them invest less, or save less for their retirement. So they aren’t cost free either.

IMO the best move with regard to raising taxes would be some kind of replacement for council tax that better reflected the underlying value of property than a set of ‘bands’ from 1991. Council tax is highly regressive - a flat tax on assessed value (perhaps capped at a certain amount) would be fairer (though even then not actually progressive) and in line with how our friends in America and Canada do property taxation. But but but. It would be a hellish political process to do - screams of grannies priced out of their six bedroom detached houses in North Oxford - and so, I imagine Labour would balk.

Which leaves scenario three. Cut not. Tax not. Borrow. And hope economic growth means that the borrowing is sustainable. That’s not new. Britain has run budget deficits almost every year in the past few decades save a couple of early Blair government years. The problem is that the deficits during both the Great Recession and especially Covid were much larger than standard. Meaning a much higher national debt and hence interest payments. So borrowing is not risk free as an economic or indeed political strategy.

Fun choices right? And that probably explains the dourness of Starmer’s recent speeches which are like a bizarro Tony Bennett - ‘The Worst is Yet to Come’.

Having placed the Ming vase on the plinth, the man running the museum is now shushing the visitors and glaring at them. The policies on offer are currently - tax rises in the autumn, no smoking in public, and no youth mobility program.

Shut up, stop complaining, and look at the lovely intact Ming vase.

Starmer’s sternness may have worked decently when it came to locking up racist rioters - something far more popular among the general public than on alt-right social media. These idiots had broken the law and are paying the consequences - in similarly draconian fashion as the 2011 rioters.

But the rest of the public deserves some joy. Indeed, I suspect many were rather anticipating it. The end of fourteen years of Conservative-led government was greatly enjoyed by many younger or more liberal voters. I imagine they would have hoped to feel just a bit better about what came next. To have a government that showed a little glee. A little vim. A little hope. Instead, they are being asked to stand at the bedside of a very ill nation while the doctor looks on, shakes their head, and pronounces that things were worse than they had ever thought.

In some ways, it feels like the concerns of the old era are still making the political hay. Labour, for understandable electoral reasons, have got locked into a defensive crouch, worried about offending every last socially authoritarian Labour Leave voter. But as John Curtice has argued, that is actually a very small group of Labour’s current voting base (or indeed of the Lib Dems and Greens who were another almost twenty percent of the vote in July). And so that’s why we can’t have nice things.

I never anticipated that Labour would move quickly away from their No Single Market, No Customs Union line. It will take lobbying by business, unions, and yes citizens to make that happen. But the rapprochement, such as it has been, with Europe has still been pretty mealy-mouthed. Politicians often lag changes in public opinion and then find themselves running to catch up - something regular readers will know I wrote about in my comparison of Brexit and the Prohibition. I do hope at least part of the Labour Party is keeping an eye on this - otherwise it is going to have a very disappointed base who may opt to stay at home next election when they don’t have the Tories to throw out.

And more generally, Parliaments are short. I totally understand the need to get the bad stuff out of the way at the beginning. Generations of political scientists can tell you that it’s growth in the last year, maybe two, before an election that matters. But you do need that growth. You need a plan for that. The pain now has to lead to gain later. And people won’t thank you for preannouncing the pain if there’s never any upside. You can’t make people eat their greens and then forget to serve dessert.

The comparison is perhaps a little unfair but honestly look at the contrast with Kamala Harris and Tim Walz. Yes, the joy stuff is overdone. But their vision is relentlessly positive. They too are denouncing the previous conservative administration (amazingly from being in the actual position of the current incumbent… wild) with a ‘we’re not going back’ line. But the mantra is much more forward looking - all about ‘future’ and ‘freedom’.

You may find it all terribly American and wooly. But it is making Democratic voters feel good about themselves. And I think there is an element of self-fulfilling prophecy here - when you feel good and you win, you feel positive about the economy, you spend and invest more, and so on and so forth. That’s how Republican and Democratic voters tend to behave when their party wins office. But the winners of the UK’s General Election are not being encouraged to feel good, go out and spend, seek exciting new investment opportunities, etc etc. They are being asked to prepare for tough times. That may be honest. But it’s also pretty depressing. And I suspect might produce a self-fulling outcome of its own - the doom-loop.

So Prime Minister, well done on the vase. It’s uncracked, pristine, and admired by all. But the vase was only the beginning. You have to keep it in one piece to get to run the museum. But that’s not the main job.

The job is to set a policy agenda and vision that allows you to preside over a content, optimistic, galvanised nation. To make the museum’s visitors happy. That won’t be accomplished through stern lectures and proverbial punishment beatings. Those are more likely to lead people to look to another leader who can promise the earth, where even if they know he’s lying, people can pretend otherwise and still feel good about themselves. And, well, we just had that guy run the museum, and the exhibits were torn down, the museum shop ransacked, and the music was still blaring at 3am.

I hope the people in Downing Street read your Substack. This is spot on.

The 1997 General Election took place on 1st May; the 2024 General Election on 4th July. Blair had well over two months before the Summer recess; Starmer, just over a week after the King's Speech. It's pretty difficult to make changes that require legislation when Parliament is not sitting. And even when they do return from the Summer recess, they will be quickly into another recess for the Party conferences. Focusing on the chronological first 100 days as if it were a US Presidential election is misleading; we should be looking at the first 100 days on which Parliament is sitting to give a fair comparison.