Move Fast and Break People

Are we entering a new era of disruptive politics? How should we feel about it?

Quick tip. Never write an opinion piece during the first week of a new administration, at least not one that predicts the global long term implications of a regime that’s been in power for just hours. A tip that might have been useful for a certain, Simon Case CVO, previously the top civil servant in Britain, under the premierships of Boris Johnson, Liz Truss (‘memba her, eh?) and Rishi Sunak. Just a few days into Trump 2.0, Case wrote the following piece for that fount of reasonable op-eds, the Daily Telegraph:

A headline that has aged like fine milk, or indeed like the legacy of Case’s benighted time running the civil service. Now, let’s be fair. Case did use a conditional phrasing - a standard go-to of Telegraph opinion pieces (“if the blob just goes away, Brexit Britain can soar like an eagle” etc etc).

If, indeed, Trump is successful in his plan to reinvent government it could be the global blueprint - not least for other strong-men leaders who want to ignore laws and norms, I suppose. But I think it’s fair for me to take issue with the ‘if’ clause here. Because the last week has seen ‘reinventing government’ through the form of arbitrarily turning spending on and off, shutting down an entire department without Congressional approval, and seizing control of the US Treasury’s computer systems for ends not entirely clear.

Now perhaps, that’s what Simon Case meant. He did, very briefly, overlap with Britain’s very own government disruptor - Dominic Cummings. Cummings, for all the critiques made of him, has long had an effective disruption strategy - he disrupted the Northeast devolution referendum, the Department of Education under Michael Gove, and of course Britain’s membership of the European Union. He then had plans under Boris Johnson to further disrupt the civil service, science policy, and procurement - some of which were quite successful (and indeed some were salutary - say on skilled visas). Say what you will, but that’s actually a blueprint.

What’s going on in the US right now is rather more inchoate. Yes, it sort of follows some of the ideas in Project 2025, a Heritage Foundation backed plan that Trump decried during the campaign but has - psych - nonetheless re-animated in his actual Presidency. You can see this in some of the early executive orders - say on migration, birthright citizenship, LGBTQ rights etc - and other actions emanating from the White House and Stephen Miller in particular.

But there is also an entire wing of disruption under the lead of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (with the lol-brained acronym of DOGE). Musk over the weekend has decided that USAID, the world’s largest distributor of development funds and founded - through, you know, laws - during the Kennedy administration is ‘evil’ and a ‘criminal organization’. USAID employees found themselves unable to return to work on Monday and by close of day, various Democratic lawmakers - roused from a soporific first week of opposition - were trying and failing to enter, and then making speeches outside, USAID buildings.

Musk has not stopped there. The exact reporting on this is hard to follow - in particular about the young people involved - but Wired has the most extensive coverage. The long and short of it is that a small group of twenty-something men, with various connections to Musk’s enterprises, appear to be working for DOGE, along with other Musk and Peter Thiel associates, in taking control of the Office for Personnel Management and Government Services Administration. These are the core HR functions of government. Most importantly, DOGE appears to have been given access to the US Treasury’s databases and the federal payment systems by Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. This means that a new group of not-obviously vetted Musk associates may have access to every American taxpayer’s Social Security number and to every payment made to an entity that contracts with the US government. A leak of payments made to various Lutheran charities to General Mike Flynn (remember him) suggests that this data is not entirely secure. Musk is vowing to cancel entire grants - with exactly what powers unclear.

And then we have Trump himself and his tariff-lust. In a way this is comfortably familiar stuff. Trump loves tariffs so his threats are plausible. But what he loves even more is other leaders kissing the ring. And so, so far of four countries that have had tariffs threatened - Colombia, Canada, Mexico, and China - only China has actually received them. The others all made promises that apparently satisfied the President’s demands. Colombia to let American planes return deportees, Mexico and Canada to prevent the flow of fentanyl into America. Reporters quickly noticed that in all these cases, the leaders of those targeted countries simply rebranded things they were already doing (accepting deportees, placing troops on the border) as being done in response to Trump’s threats. Kabuki theatre at its finest.

Trump’s own foreign-policy disruption so far - with the exception of the actually-existing (at time of writing) tariffs on China - seems to be rhetorical rather than in reality. But that doesn’t mean it won’t have real-world effects. Every time Trump threatens Canada with tariffs, business owners with cross-border activities will think, is this really worth the effort? For a recent example, think of the British government’s ceaseless flirting with a no-deal Brexit they were never going to be able to sustain and the deleterious effect this had on investment in the UK over the past half-dozen years.

So let’s assess the disruption so far. The Project 2025-inspired executive orders are what we expected. Probably unconstitutional in many cases, likely stayed by the courts, and soon to enter a years-long judicial fight. Musk’s apparently extra-legal seizure of government data and plan to arbitrarily stop payments, is even more likely to get deep-sixed by the courts or Congress (the Republicans barely hold the House and Social Security payments being under threat is precisely the thing that freaks out Congressional Representatives). And Trump’s foreign threats - ridiculous sounding as they often are - seem so far more sound than fury.

One surprising aspect of this news, to me at least, is how little coverage it has received in the UK. Our mainstream newspapers have just about managed to cover the tariffs - which (a) haven’t happened in most cases, (b) were obvious that Trump would do from day one, and (c) are an entirely legal and ‘normal’ (if undesirable) use of Presidential power. The possibly extra-legal access of a bunch of twenty-something guys to the identity details of every American - what’s that mate?

The Times - the UK’s alleged newspaper of record - had HALF A PAGE (page 23 since you asked nicely) on Monday on the events over the weekend - about the same as it had on a French council asking its employees to pretend to be trees. Honestly, there have been more op-eds by credulous opinion writers praising Trump for his ‘decisive action’ than there have been lines of coverage about what these actions actually are. These writers are being paid money for old cope.

Anyway, let’s return to Mr Case and his ilk. What exactly is the Trump strategy they are so excited about? Disruption, yes. Flooding the zone, yes. But what will it all add up to? And is disruption worthwhile even if it doesn’t have clear targets?

Maybe. But since these writers don’t have a theory of disruption, they just assume it’s good for the sake of it. Move fast and break… people, I guess.

This is not going to be a piece that says all disruption is pointless flimflam. Nor, as you can probably tell from my description above, do I think this really could amount to a ‘global blueprint’ at all. But I do think - and since you foolishly subscribe to a Substack called Political Calculus, written by a bona fide Professor, perhaps you agree - that it’s worth setting out what we know from social science about the merits and demerits of disruption.

When Disruption Works

You might have wondered about the image at the top of this post. Regular readers will know I love shout outs to social science classics (James C Scott, Lea Ypi, William Riker, Thorstein Veblen). This time I’m going with the American political economist Mancur Olson.

Olson is most famous for his Logic of Collective Action - the book that first formalised the idea that groups having the ability to act as one - a pretty fundamental tenet of, say, Marxism - was not entirely obvious. Olson argued that even when a whole bunch of people shared the same objective, each of them would prefer to free-ride on the efforts of others, provided they couldn’t be excluded from the objective, should it be achieved. Since everyone wants to free-ride, no-one will end up contributing, and the objective is never attained. Hence the logic of collective action is: it won’t happen. Unless, that is, either the costs are actually worth paying for a single actor, or if people can be cajoled to contribute through what Olson called ‘selective incentives’ but what we might call sticks and carrots. Trade unions, business organisations, political parties - all of them need to use sticks and carrots to keep their members in line.

Banger of a book but not precisely the one I want to focus on here - though it is indeed relevant to the argument made in Olson’s other well-known book - The Rise and Decline of Nations. You see, Olson was no fool - he saw that groups did indeed exist; that collective action did indeed happen. But it would happen through smaller, highly disciplined groups. The general public? That is not a well-organised group. It is diffuse and disorganised. Things that might benefit all of us collectively but that hurt small, concentrated groups won’t happen. The public can’t act as a group but the special interests can. And that’s why you get things like, oh I don’t know, tariffs.

Olson’s Rise and Decline came out in 1982. You can see from the subtitle what his concerns at that time were: economic growth, stagflation, and social rigidities. Sound familiar? Message for Rachel Reeves. Message for Rachel Reeves. The 1970s, like today, was an era of lower economic growth, high inflation, and a discontented public. And the blame for that, per not only Olson but many (neo)liberal thinkers of the era, lay with organised interest groups - specifically trade unions, but also business organisations, desiccated corporate bureaucracies, and ‘cartel’ political parties.

Olson’s argument was that these more concentrated actors were better at organising than the general public. So naturally policymaking would end up reflecting their interests ever more. Regulators would be captured by the businesses they were intended to regulate. Political parties would be captured by party elites and trade unions or business organisations. Monetary and fiscal policy would be set on behalf of ‘corporate’ actors - be they from labour or capital. And this meant, for Olson, endemic rent-seeking. This is economese for actors receiving higher profits or wages than they would in a competitive market.

So the solution to this Olsonian dilemma of special interest stagnation was disruption. It required political actors to break down some of the monopoly rents of business and labour. This was very much in the spirit of the Volcker monetary shock, of Thatcher’s Big Bang, of Reaganite deregulation, of the European single market. All attempts to undermine existing groups that had lodged themselves in the gullet of the economy. I realise my more left-leaning leaders might be cursing and spitting at this juncture but whether one agrees or disagrees with the 1980s political revolution, Olson at least applies a theoretical lens to understand why some people thought it crucial in order to return economies to growth. And if you don’t like this take by Olson, well don’t worry, he has another we will return to shortly.

I think the Olsonian framework is helpful for understanding the rhetoric accompanying today’s age of disruption. Listening to Donald Trump, Marco Rubio, Elon Musk, J D Vance and more, their argument is that they are performing a necessary brush-clearing of both bureaucratic stodge and corporate rent-seeking - where they define rent-seeking as DEI, stakeholder engagement, HR, and other enemies of the new populist right. You will note that they seem rather less excited - currently - about disturbing the monopolists of big tech, though I suppose I should note that Vance, at least in the past, has played footsie with restraining big tech, along the lines promoted by previous FTC chair Lina Khan.

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves have also been breathing the bracing air of deregulatory fervour, inspired not a little by the reality of a new Trump administration. When Reeves asked Britain’s regulators for their plans for growth this was about removing, not adding regulations. When Starmer talked about the civil service being in the ‘tepid bath’ of managed decline, he was implicitly making an Olsonian argument. And of course Dominic Cummings saw disruption in a similar light - as removing unnecessary impediments and undermining lazy rent-seekers.

This is not completely bonkers. Anyone who has worked in an organisation with more than fifty employees will have a trove of horror stories about superfluous rules and regulations. Most academics, who display abject horror about Musk and Trump, are rather less generous to their own employers and their rules about reimbursement, procurement, and form-filling.

Order can be stultifying. In Why Politics Fails, I have a section called ‘The Problem of Order’ where I talk about how too much security can be malign. I write about the famous Danish Law of Jante - a social norm that no member of your community should be seen to excel in any way, lest they be viewed as stepping out of line (the actor Alexander Skarsgård, when on Stephen Colbert’s show, once mentioned he could not accept his compliments about winning an award lest he violate the Law of Jante).

And an absence of disruption can lead to technological or cultural stagnation. The Nobelists Daron Acemoglu and Jim Robinson have a great paper arguing that elite rent-seeking by government and actors close to it can block important technological change. Bob Putnam argued in Bowling Alone that there can be a ‘dark side’ of social capital - very high trust communities can be completely conformist and suffocating. And in case anyone thinks that highly ordered and norm-based institutions are always good, let me introduce you to German academia.

Disruption is what shakes stagnating countries out of their torpor. It is what derails monopolists; destroys sacred cows; weakens embedded elites. It can be - often is - a force for good.

When Disruption Fails

But just because disruption is sometimes worthwhile, doesn’t mean it always is. Marxists often talk about the idea of ‘heightening the contradictions’ - pursuing crises and disruption to galvanise the fall of capitalism and the coming of socialism. Maybe. But in my view, what you normally just end up with is higher contradictions.

Sometimes, when we want everything to be different we end up like this…

That cartoon got a lot of play in the era following the Brexit vote, usually by Remainers, followed by Leavers calling them conceited and patronising. Plus ça change.

Changing things need not be chaotic. But I don’t think we want to forget the Second Law of Thermodynamics - things do tend towards entropy. The chance of any random change being better than the current situation is not enormously high unless the status quo is completely intolerable. I know some people do really think the status quo is unbearable - but quite often they seem to be doing so from behind laptops in heated detached homes in pretty provincial towns. So I suspect they don’t really mean it and are cosplaying anarchists.

And stability can be good. I know, boring right. But this is a message that I wanted to convey in Why Politics Fails - if you want long-run prosperity you tend to need a stable environment to get there because people will only make costly investments in situations of fairly clear risk/reward tradeoffs. If your policy making is completely chaotic then many consumers and businesses will withhold investments - they will fear expropriation, or market collapse, or ever-changing taxes or tariffs. As social democrats discovered you can’t force capital to invest - what Adam Przeworski and Michael Wallerstein called the ‘structural dependence of the state on capital’.

What’s quite surprising about the past decade is that politicians of the right seem to have driven into the same obstacle that long blocked their opponents on the left. Brexit has produced - and there is now very little debate over this - an investment environment in Britain that has been stagnant for almost a decade. You can’t command businesses to invest (unless you take them over), you can’t insist that firms export to new markets. You have very little power as a disruptive politician to make people who want certainty feel good about the uncertainty you have created. No wonder you might pout and say ‘fuck business’.

There is ample evidence in political economy that political institutions that create stability are good for investment and for growth. Irfan Nooruddin, for example, shows much higher levels of business investment in countries with lots of institutional veto players and coalition governments. But perhaps the best proponent of the benefits of stability was some guy called… Mancur Olson

In a seminal article called ‘Dictatorship, Democracy and Development’, Olson made the argument that democracy’s killer app is its relative stability compared to dictatorship. Very much not the argument that fans of Communist China or authoritarian Singapore like to make. But let’s follow the logic.

Olson argues that in anarchic, state-of-nature like conditions, people who seize power will know that their hold on power is tenuous and volatile. They will seek to get what they can, while they can. Olson refers to these rulers as ‘roving bandits’. They predate on the people they rule; arbitrarily and rapidly. They have little interest in the economy they rule growing because they are unlikely to be in situ to benefit from it. They disrupt by their very nature but the disruption only benefits them.

Olson contrasts them to ‘stationary bandits’ (not pen thieves, check the spelling). These are dictators who remain in place over the long run. Let’s call them monarchs. Because they know that they, or their heirs, will be in power in the future, they have an incentive to provide a stable legal framework that helps the economy grow. Or more simply they avoid slash and burn expropriation of their subjects. They still, I should note, are bandits. They want their tribute. They just want to maximise their take over the long run. So to be techie, they internalise the externality of their incentive to predated on their subjects. They rationally withhold their avarice.

And then there are democracies. For Olson, these are best because the predation - such as it is - is legalised and from one citizen to another; i.e., it’s the taxation we associate with modern mixed economies. Democracies are more stable still than monarchies and, what’s more, they can use taxed resources for universally productive purposes such as education or infrastructure. This stability produces much higher levels of investment and hence of development.

In this view of the world, democracies are rich precisely because they are NOT disruptive. Development comes from stable expectations, stable expectations come from a rule of law, from constraints on the executive, from a peaceful rotation of power. In my book with David Samuels, we argued that the chief proponents of democratisation in autocratic countries are merchants / the bourgeoisie / the commercial classes, because it’s wealthy people who have the most to fear from the arbitrary grabs of autocrats. Dictatorships’ secret weakness is that they cannot credibly commit not to seize your stuff.

Here disruption is the enemy. It’s not a force that pulls the rug out from those embedded in power. It’s the secret weapon that those in power use to predate on everyone else.

Making the Omelette

Typical bloody social scientist. When asked a simple question like “is disruption good or bad?”, their answer is “both, I guess.” Don’t blame me. Blame Mancur Olson.

But our story about disruption is actually a story about democracy itself. Yes, democracy can be stabilising - anti-disruptive - as compared to the arbitrariness of dictatorship. The rule of law, respected institutions, peaceful rotation in power - all the stuff of stability, certainty, and one hopes, economic growth.

But, democracy is also about self-rule, about changing who is in power - about the ability to self-correct. To go back to Dominic Cummings, inspired by the physicist David Deutsch, he argued that the key reason to support Brexit was ‘error-correction’ - that a sovereign democracy could learn from and correct its mistakes. Whatever one thinks about the reality of Brexit, that’s a consistent viewpoint and one that has a very different, disruptive account of democracy.

My sense is that this is the belief of those people around the world - maybe even Simon Case - who are on the Trump train. That the US has been on the wrong path - certainly the view of the American public when asked in polling - and that the democratic election of Donald Trump was a form of error-correction. It was democratic disruption.

That question, though, is whether that election will also turn out to have been disruptive of democracy.

At this point, I don’t think I want to get into the business of making grand pronouncements on whether there has been actual democratic backsliding in the US. A while back I bemoaned various coders of democracy (Polity, V-DEM) being too quick to downgrade American (and indeed British) democracy in 2016 and 2017. I felt the coders might be eliding their distaste for the policies of these governments and the health of actual formal democratic institutions

Some of what has transpired over the past two weeks is business as usual in America. Presidents usually are given fairly high leeway by their opponents in their Senate in terms of their Cabinet picks - so the very narrow approval of Pete Hegseth as Defence Secretary, for example, is not in itself unusual (even if Hegseth’s relative qualifications for the job are). And indeed, Matt Gaetz didn’t make it to confirmation (though it looks like RFK Jr, Tulsi Gabbard, and probably Kash Patel will all get confirmed).

Similarly, Trump’s tariffs, while destabilising of existing alliances, and also frankly so far ineffective at actually producing anything other than kabuki theatre promises from Colombia, Mexico and Canada, are a Presidential prerogative.

When we come to executive orders it’s slightly more borderline territory. Executive orders have proliferated over the past two decades - from GWB, Obama, Biden, and of course Trump term one. Lots of (conservative) people moaned about Biden cancelling student debt through an executive order - indeed, various federal courts eventually ruled against it. Trump’s executive orders include a variety of commands that are also likely to be ruled unconstitutional - particularly that over birthright citizenship, which would require a complete re-interpretation of the 14th Amendment.

However, the Supreme Court is highly conservative and it’s possible they may decide to go against decades or centuries of legal opinion. Clarence Thomas and Sam Alito absolutely will. But John Roberts, Amy Comey Barrett, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch are less predictable. We will see. Either way, I suspect that nasty or not, these executive orders will live and die in the standard judicial way. It’s only if Trump pulls an Andrew Jackson and says “the court has made its judgment, let’s see them enforce it” that you end up with a proper constitutional crisis and meet the criteria for democratic backsliding. We are not close to that yet.

In my view, the biggest concern - and yet the least covered by the British press - is what is going on with Elon Musk and DOGE. It’s not really clear what Musk’s exact government status or security clearance is, let alone that of the various DOGE interns and employees. But they appear to have shut down an entire department - USAID - that disperses more foreign aid than any other entity, basically on their say-so. The US is not Britain - the executive cannot unilaterally change or remove departments. It needs to be done through the legislature. As the British case shows, it might be disruptive to get rid of government departments but it is not per se anti-democratic - after all, the Conservative government in the UK also got rid of the independent foreign aid ministry and merged it with the foreign ministry - basically exactly what Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, says is going to happen to USAID.

But if the legislature don’t approve of this, that’s a constitutional crisis in the US because it’s Congress’s choice, not the President’s, and certainly not Elon Musk’s. What has happened, then, is plausibly a weakening of democracy. The problem is though that we don’t know what Congress’s position is on this - since both houses are controlled by the Republicans, perhaps their lack of vocal opposition signals approval - in which case it’s not a South Korea style constitutional crisis. But it’s this potential extra-legal set of DOGE activities - with USAID, with control of the Treasury payments system, with the removal of government inspectors - that we should be worried about, if we are worried about US democracy. We shall see.

But there is something else we should worry about. Something that is at the core of disruption and that is so easy to overlook for people writing Telegraph op-eds from the warmth of their expensive London townhouses. Disruption disrupts people’s lives. There is the old adage that you can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs - an adage usually used by people who are very certain they will never be the egg. To paraphrase Mike Tyson, everybody likes the idea of disruption, until disruption punches them in the mouth.

Back in the summer, I wrote a piece inspired by Lea Ypi’s Free and James C Scott’s Seeing Like A State. What I felt underpinned both books was a deep respect for the lives of ordinary people - an understanding that grand ideas and projects of the state have personal human consequences.

That’s just as true of disruptive government. Yes, we cannot make public policy in a world where everyone who could be negatively affected gets a veto - politics has to have losers as well as winners. But blithely smashing through losers for the sake of it is careless, sometimes sociopathic.

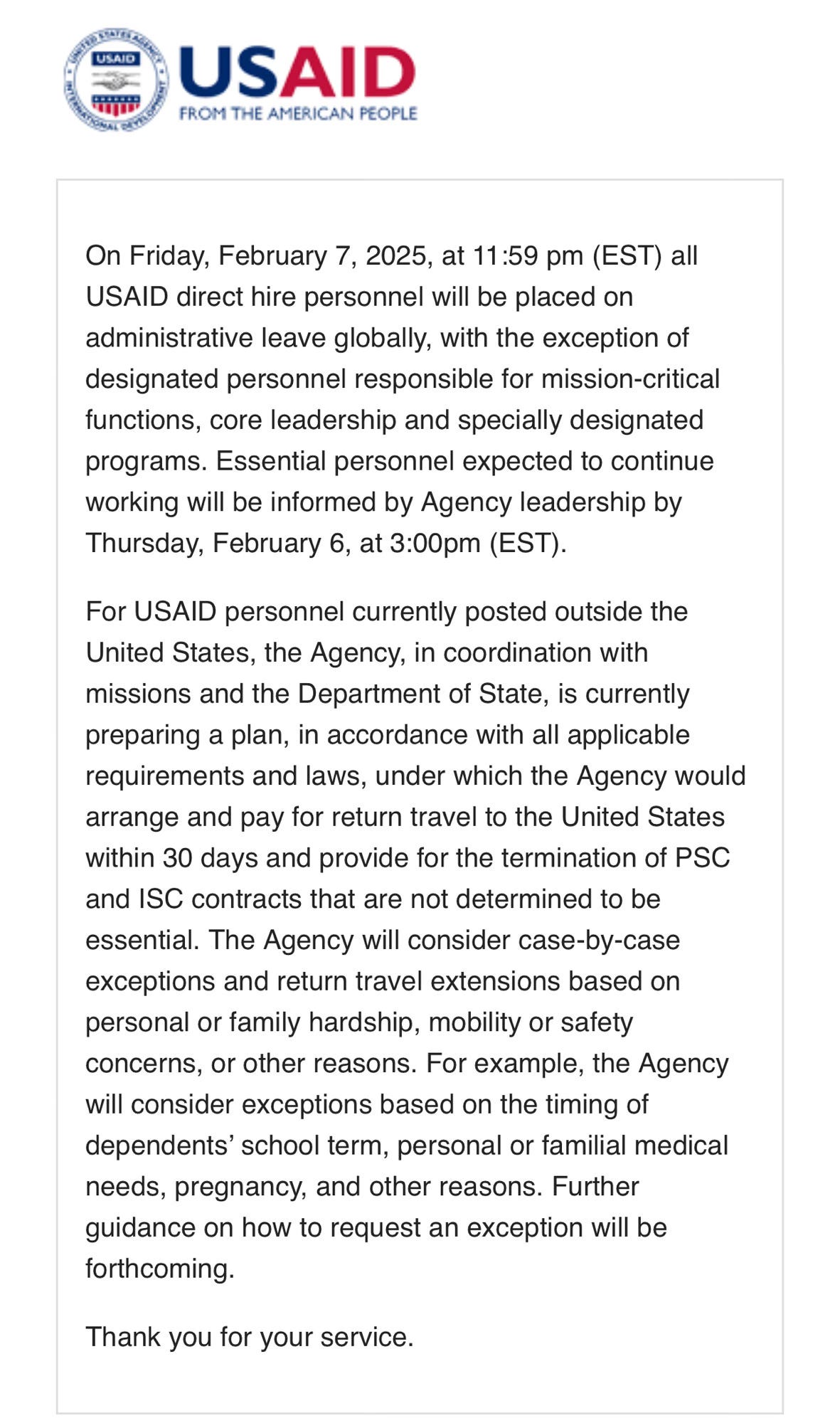

It’s worth looking at the human effects of Elon Musk’s ravaging of USAID. The message below, from the department, was just released. Around ten thousand people, most living abroad, and often performing charitable tasks on behalf of the US state for lower salaries than they’d earn elsewhere, have been told to get out of their host country within thirty days. Yes, there are a few exceptions about school terms etc but this is massively disruptive and aimed squarely at American citizens. And if you care about national security, it may also affect some people embedded in USAID, who have… um… connections to other US agencies.

Or think about Trump’s new ‘plan’ for Gaza, announced overnight - the USA will take sovereign control of Gaza, expelling its previous citizens, and rebuild it into a great piece of seaside real estate. The lives of those living previously in Gaza - too bad, maybe they’ll earn enough in refugee camps in Jordan or Egypt to one day be able to afford to return to Monaco on the Levant.

Many of the policies of the first two weeks of Trump 2.0 have the feel of ideas coming from that bloke at the pub, who is going to think outside the box and put the world to rights. The impact of those ideas on those affected - not my problem, mate.

Ultimately, like the guy down the pub, I don’t think the Trump administration has an actual theory of disruption. I suspect there will be quite a bit fucking about and finding out.

However, they do have a theory of governance, even if no-one wants to say it out loud. It’s an old theory. One that has been with us since at least Thucydides. One familiar to leaders of major countries today from Russia to China. It’s might makes right.

And Britain’s role in all of this? Well it’s Thucydides again - read the Melian dialogue. The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must. The UK can try and become a disruptor in its - possibly vainglorious - plan to become an AI superpower. Disrupt all you want. Just be aware, there’s a bigger disruptor over the pond. And when they choose to disrupt, all your plans might be for naught.

As advertised in my last post, Rethink covered AI and intellectual property last week. This week (4pm Thursday, repeat 8pm next Monday) we’re looking at medical data, next week at crime prediction and prevention, and after that the global economy and finally post liberalism. So lots to come! Do listen in and let me know if you have ideas for future Rethinks.

Thank you for this great piece. One note: as a Hungarian, I love nothing more than bragging about the Hungarian background of great social scientists (John Harsanyi, John von Neumann, etc.), but I think you are mistaken about Mancur Olson. He was US-born to a Norwegian immigrant family, it seems.

Interesting piece. I know it's rude to enter a political science discussion and reframe it through a different disciplinary lens, but I feel I have to. This is a systems problem, not a political problem. In brief, systems are clusters of parts that come together and then break down again. What stops a system from breaking is resilience - or adaptability. This allows a system to continue without breaking down. OK, systems operate at different scales in time and space. The example often given is a forest. This has seeds, saplings, trees, woods and eventually forests (parts coming together). The forest sits in a broader ecosystem still. Seeds and saplings fail a lot. Ecosystems fail very rarely and usually in response to one off big bang type impacts. Imagine an insurance tower in Lloyds. The bottom layer gets blown out pretty often. The top layers - and ultimately the market layer - hardly ever blows. It's a resilient system that can take a lot of pain without breaking the overall structure. So an important lesson here is that systems become resilient when lower levels can blow out (without sinking the vessel). But what if the lower levels are protected? Then you lose modularity in the system. The layers start to become increasingly interconnected. It becomes harder to adapt to change and the only way to change things is to crater the whole system. Again, the goto example here is forest fires. Lots of regular little forest fires are good for forest health. Putting out small fires compromises the system because dead wood builds up on the forest floor and turns into a huge conflagration. Hopefully, some of the very obvious parallels are becoming obvious here. Stewart Brand, a clever MIT chap, has applied some of these ideas to political systems. Instead of a seed / sapling / wood / ecosystem, he frames political systems as follows:

Fashion (changes very rapidly and frequently)

Commerce (changes pretty rapidly and frequently)

Infrastructure (changes every decade or two)

Governance (changes very infrequently)

Culture (changes over centuries)

Nature (changes over geological time)

The point about these layers is that each one represents an adaptive layer. A lot of collapses in the lower layers are healthy for the system. But collapses in the higher layers are pretty critical. Now when these lower level collapses are stopped for whatever socially / politically good reason, then the system becomes more interconnected and harder to change. Although I am sitting in a (sort of) heated house in a pretty market town, I am not alone in sensing that my control of my immediate environment has become increasingly constrained. This is because systems are becoming more and more closely coupled. My sense of being able to affect stuff at the top has diminished. The layers of local politics, special interest groups even Parliamentary democracy have all fused. So it feels like the only way to change anything is to kick out the entire system. In this context, we get to Bannon / Cummings / shock doctrine. Shock doctrine, in systems theory, is a phase shift. In a phase shift, all the old rules / paradigms etc; get collapsed and new stuff gallops into the gap. This is a little abstract and I explain it more deeply in my posts, but the point about a system level collapse is that you often see speciation. So the fossil record will show you lots of slow, incremental change - then bang, the asteroid hits and you see all these new species taking over. It is not, in my opinion, any coincidence that we saw super wealthy people speciating into a billionaire class after 2008. Now, any post on systems thinking has to mention Nicholas Taleb and if he wasn't such a self-regarding iconoclast, he might have written books in a Haynes manual style instead of as sacred texts that need three levels of interpretation. The point is, one of Taleb's big ideas (stolen from systems thinking) is that old things work because they've been around a long time. A jury is a useful thing but who knows why? A book is a useful thing. A knife is a useful thing. AI is not that useful. Maybe 10,000 years from now we'll have a different view. But right now, it's just a *fashionable* thing that hasn't been stress tested through a systems lens. So, back to the topic in hand. How do we know when to stick and when to twist? The answer is that *if* you want a stable, resilient system, you twist a lot at the bottom layer (in this case, this would be lots of experimentation in ways to improve democratic decision making at the level of the citizen) but very LITTLE change among the institutions. In the case of the civil service, you'd let them do all the repetitive, stable, ordered work AND you'd run some taskforces to accelerate & run experiments to keep improving the bottom layer. We have made a pretty good fist of making an adaptive political system with parish councils > local gov > MPs > Parliament etc; But the system has become too interconnected. It's not adaptive at teh local level. Everything is driven from the top. This means the system is fragile and very easy to push over (Cummings / Doge whatever). And mark my words, when you push over a big system like this, something new will emerge. In the UK, we are finding that pushing over the Brexit system is leading to cascades of damage to our economy. Reform is the beast that emerged. In the US you may even get fascism. I have now written so much i should have turned it into a post. Anyway, please read Stewart Brand's paper and, if you can bear the self-satisfied tone, all of Taleb's books. Then top this up with a healthy dose of James C Scott and suddenly, you'll be hit by a blinding light.