I may have been away but the beat went on. There have been a few unmissable episodes of What’s Wrong With Democracy since I last wrote. First off, an episode on the courts featuring my old colleague Kathryn Sikkink from Harvard, Ben Stanley from SWPS, and Fida Hammami from Amnesty in Tunisia. Then an episode on polarisation featuring Noreen Hertz from UCL and Wendy Via from GPAHE (where we talked about Project 2025 before it had hit the news!). And most recently an episode on apathy and youth voting featuring John Burn-Murdoch from the Financial Times, Jake Grumbach from UC Berkeley, and Viktor Valgardsson from Southampton.

Finally, you can catch me to talking to Adam Fleming on BBC Newscast about how the year of elections is going.

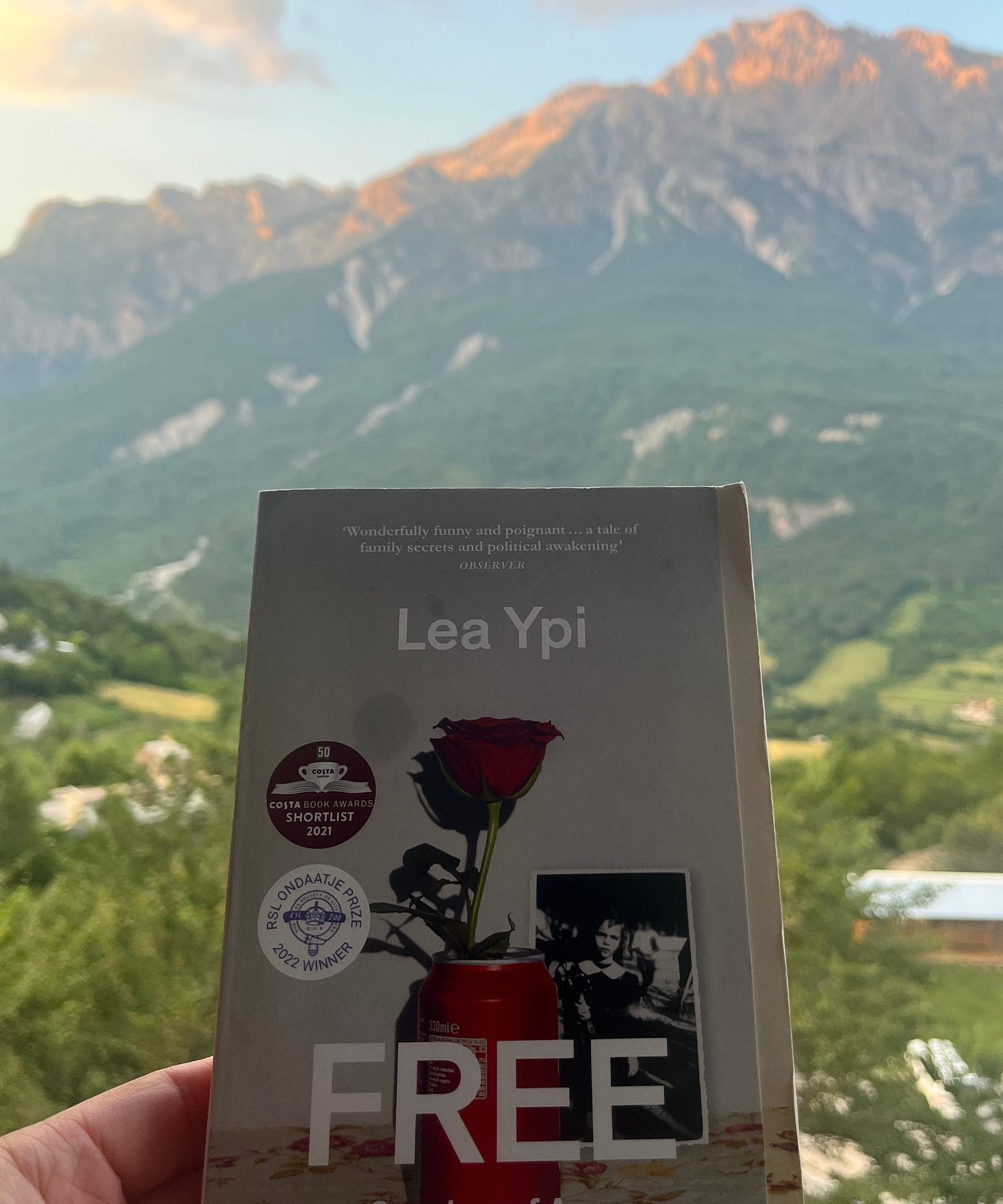

There was an election. And then there was a holiday. To Albania, as it turns out. Because I am an academic, my holiday was spent reading a book by another academic. But in stark variation from my normal practice, it was not an ‘academic book’. It was, instead, the memoir Free by the LSE political philosopher Lea Ypi. As you can see in the photo above, framed by the Albanian Alps, this is the rare book written by an academic that makes the Costa Book awards shortlist. Let’s just say that for all my attempts in Why Politics Fails to speak to a broader audience, I’m not Costa Book award level.

It is an outrageously brilliant book. The book is made up of 22 ‘anecdotes’ from Ypi’s youth, growing up in Albania. As ‘coming of age’ narratives go, this one has a quite stark transition from childhood to adolescence - the fall of Albania’s Communist dictatorship in 1990. The first ten chapters follow Ypi’s childhood under the world’s most isolated regime, save perhaps that of North Korea. Until 1985 this was a regime ruled by the terrifying Enver Hoxha, a Communist leader who systematically murdered every opponent - and ally - both within and outside the Communist Party over his more than forty years in power. Afterwards, little except the leader’s identity changes. Until 1990 and the deluge.

This is a period in which everybody has to watch what they say, how they stand in line, whether they point out to their parents’ friends the absence of a photo of the great leader. And as in so many other Communist regimes, but more so, citizens develop their own languages to describe their political reality, without explicitly stating it. That gives the first half of the book an ‘unreliable narrator’ feel - as ten year old Ypi is told about, and talks about, her relatives ‘graduating university’ after several decades, or about Stalin’s hidden smile underneath that hirsute moustache.

And then 1990 happens - and the ‘hooligans’ causing trouble are revealed to be citizens protesting and eventually bringing down the regime. ‘Graduating university’ is revealed to be ‘leaving political imprisonment’, the true origins of Ypi’s family tree are finally revealed to her, and so forth. I don’t want to spoil the surprises, though of course the writing brilliantly conveys that all is probably not as it seems in the pre-1990 period. But in a sense, there is no surprise - we know that the totalitarian regime of Enver Hoxha and his successors will fall. We know that Ypi and her family will become ‘free’. But ‘free’ how?

The middle of the book marks the transition, as Ypi puts it in the last line of Part I: “Things were one way, and then they were another. I was someone, then I became someone else”.

Part II marks a world of different freedoms. Before transition, the regime defined ‘freedom’ as being made free from having to worry about economic hardship (within reason, Albanians were extremely poor but the government provided work); not having to worry about making political decisions (you couldn’t); and not having to worry about foreign powers (the regime, having sent the fascists packing, then sent the British and Americans packing, then Tito’s Yugoslavs, then the post-Stalin Soviets, and finally Maoist China after Nixon’s overtures to the CCP).

Torturing the concept just a little, freedom in Hoxha’s Albania was a seen as a positive liberty (Isaiah Berlin’s famous term) - the regime empowering its citizens to be free to be good communists, away from the exigencies of capitalism and imperialism, and it also turned out, the cursed ‘revisionism’ of post-Stalin communism.

And after communism? A world of ‘negative liberties’ - freedoms from. Freedom from the state telling you what you could say, who you could associate with, what you could buy, where you could go (in Albania or elsewhere), what you could earn, who you could vote for. The freedoms of liberal democracy.

The course to freedom in liberal democracy is not smooth. It involves structural adjustment to the economy. As Ypi’s family learns, it means letting people down, firing them, exposing them to the sometimes harsh realities of economic freedom. It means that people can leave. At least while other countries let them arrive. Until they stop and start ramming boats full of fleeing Albanians, condemning them to drown.

It means freedom it invest, in outlandish schemes that promise to double your money every sixth months. And it means freedom to vote for political parties that back these pyramid schemes.

And it culminates in a new disaster - the year of 1997 - when Albania descends into anarchy, not long after the end of decades of Hoxha’s tyranny. That particular chapter in Ypi’s book is written as a diary. A journal of chaos and families torn asunder. Where disorder reigns in a land habituated to a terrible order.

Ypi herself faces the tragicomic challenge of trying to complete her high school exams during utter collapse. And soon after she moves to study in Italy, then eventually to a postdoc in Britain (at, but of course, Nuffield College), and then to her position as a Professor at LSE. She was recently elected as a Fellow of the British Academy, the first Albania to receive that honour - a reflection of her pathbreaking work more broadly in political philosophy.

I am not a philosopher. I can’t speak with expertise to Ypi’s philosophical work on cosmopolitanism or Kant. But I am an empirical political scientist interested in how people make sense of politics, how they engage with it, and how politicians engage with them. To paraphrase Leon Trotsky - you may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you. The human experience of government - both totalitarian and anarchic - is the core theme of Free. How do you get by day to day under arbitrary but draconian rules? What do you do when someone just removes them all? Are you still the same person?

And that leads me to James C Scott, the Yale anthropologist and political scientist, who died recently. Scott was, to my mind, one of the two or three greatest minds in the social sciences of the past half century. It’s impossible to do justice to his long career, perhaps even to a single of his books, in a post - so I won’t try. But I do want to give you a sense of why you should read him, and what to get out of his books.

The core Jim Scott vision is one of states imposing order on people and people resisting that order. That might not sound profound. But the way that Scott analysed it was. For Scott, the central state uses knowledge, information, reason, and of course force to discipline citizens. And in their attempts to push back, citizens lie, misrepresent, follow the letter not the spirit of the law, and generally employ what he referred to as the ‘weapons of the weak’.

If possible, and as in Hoxha’s Albania it wasn’t always, citizens would physically escape the machinations of the central state. They might emigrate, but they might also simply retreat to the ungovernable parts of the state’s territory - to the mountains, the swamps, the deserts - to the periphery. As Scott put it in another classic, they would employ ‘the art of not being governed’.

Scott’s best known book, at least outside academia, is probably Seeing Like a State. Its subtitle, unlike almost every other academic subtitle ever written, is perfection: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. That gives a sense of Scott’s underlying politics - a deep distrust of the ambitions of central states, of technocrats, or market-makers, of the architects of what he called ‘High Modernism’.

Seeing Like a State spans quite a territory - from forestry to urban design, from the creation of censuses to the layout of Brasilia, from Lenin’s theory of the revolutionary vanguard to Julius Nyerere’s villagisation scheme in Tanzania. It is an account of language and culture - the origins for example of surnames in the desperate attempt of state tax collectors to figure out who owed them what in the village. And it is an account of physical geography - why Prussian modernising forestry initially produced ample timber for the Prussian war machine before destabilising the ecology of forests and provoking environmental collapse.

Most of all it is an analysis of how abstract human ideas and designs fare when they meet the messiness of nature and of humanity. As Scott notes, the original centres of Old World cities, from Delhi to Bruges, reflect an organic, unplanned but deeply human structure. Paths are set for human purposes: this lane bends because that latrine got in the way; this is a sneaky path through to save you five minutes gathering firewood. New World cities, and the designs of Old World reformers such as Baron Haussman, replaced curves with straight lines, alleys with boulevards, local knowledge and custom with the needs and desires of central government.

Every central designer - be they a Stalinist collectiviser, or an imperial conqueror, or a progressive lawmaker, or, yes really, a Hayekian market-maker - will fall afoul of facts on the ground, or simply smash those facts into dust. Scott then is writing in the tradition of Karl Polanyi and those other thinkers who see social life as organic and as the other parts of social science - government, the market, organised data - as imposed and artificial. Useful perhaps. But also unnatural.

I don’t want to push that too far. There is a danger in some readings of Scott and Polanyi that they applaud custom for the sake of it, that they revere ‘backwardness’, that they ignore ‘progress’. As Scott himself notes, the organic design of pre-modern cities made them ‘literally pestilential’. The past has its horrors. But the proponents of what Scott calls ‘authoritarian high modernism’ - dictatorships of left and of right - were often willing to inflict even greater tragedies in the name of re-ordering space, language, and people.

And here is the parallel with Ypi’s Free. Albanians were shifted from one high modernist vision to another. From Hoxha’s brand of (post?-)Stalinism to a Milton-Friedman-on-steroids neoliberalism. Citizens were flotsam on the ideological waves. As the forced solidarity of Hoxha’s communism ended, they reached out for old, once-banned, forms of communal solidarity - in Albania, that meant the church and the mosque. But those alone couldn’t prevent the chaos of 1997.

We are now almost three decades on from Albania’s nadir. When I went there a few weeks ago, it felt, well not that different from the poorer parts of Greece, or Sicily, or Portugal. Most everything worked well. Save the roads. The roads aren’t great.

But the country is now in the middle of an unprecedented wave of tourism and one that for now Albanians seem excited about. The lek strengthens year on year, as all the foreign currency flows in. The TV news is basically just videos of the (democratically-elected) Prime Minister, Edi Rama, talking about the fifty percent annual rise in tourist numbers and bemoaning hoteliers on the Southern coast pushing room prices too high.

The country is not perfect. But given its… umm… idiosyncratic recent history, it’s remarkably similar to other Southern and Eastern European countries. An unemployment rate of just over ten percent. Real GDP growth of just over three percent a year, fairly consistently. Fair and free elections. And amazing, friendly, helpful people.

In the Western European mind, the country is associated with crime and illegal immigration. You can partly blame the Taken franchise for this. But also Albanians were until recently a major contributor to the Channel crossings and there are of course gangs in London and Paris and elsewhere. But the country as a whole, now no longer swinging between the tyranny of Hoxha and the bracing liberty of structural adjustment post-transition seems normal, peaceful, and getting on with it.

And that says something I think about human resilience. Albanians are still treated like pariahs in much of Europe. Lea Ypi’s own family cannot easily visit her in the UK. There is a hangover in the minds of Western Europe, that somehow the high modern visions of Hoxha have scarred the Albanians perpetually. But like everyone, everywhere, they were always more than the state imagined them to be. They preserved their own secrets, their relationships, their memories, from the harshest winds of political ambition. And in time, as the designs of others were washed away, normal people remained.

This is not a travel blog but… if you’re interested in going to Albania, you absolutely should before it gets even more touristy. The image above is from the unmissable Theth, in the Albanian Alps, taken from Valter and Rita’s guesthouse, just above the valley. We spent time in Shkroda the night before, which is definitely worth a visit. After this we went to the stunning Ottoman-era city Berat, where you have to go to Lili’s Home Cooking (book!), then to the beach town of Himara, where you should take a boat trip around the coast, then to the bonkers stone city of Gjirokaster, and finally to Tirana. You’ll need a car. But as far as striking mountain, beach and valley landscapes go, Albania is peak.

I like to pretend I don’t live in an echo chamber, but I returned from a holiday to Albania 3 days ago and on said holiday also read Ypi’s book. I concur, principally, that the roads are terrible.