As ever, whenever I have what seems to be me to be an intriguing, provocative idea, I discover that smarter people than I also had it, just several years earlier. But maybe a neat idea is worth saying twice, or thrice as it is in this case.

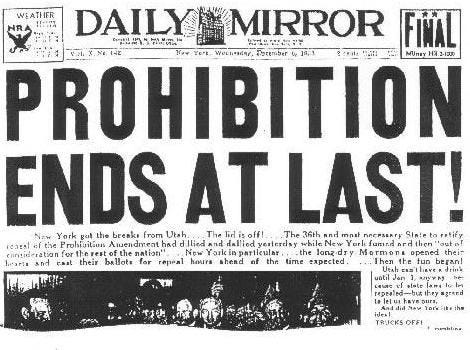

What is this mysterious idea? That there are parallels with the introduction of Prohibition in the 1920s in America and Brexit. I’ve found at least two very informed sources making this comparison a few years back. First off Flip Chart Rick, whose blog is always highly thought provoking, wrote a piece in April 2017, before even the General Election of that year, called Brexit: Britain’s Prohibition.

The second piece was written in 2019 by my Oxford colleague, Steve Fisher, whose insight into British elections is absolutely top-rate. But not just the UK it seems. His piece on the parallels between Brexit and Prohibition, which draws, as I will, on a wonderful book Last Orders by Daniel Okrent, is thoughtful and suggestive.

But here’s where maybe I can add something. Both pieces are now several years old. And while they obviously nod to the end of Prohibition as well as its introduction, even in 2019 Brexit was yet to actually begin. In Prohibition terms, this was like the end of the First World War, where it became clear that anti-German sentiment (ironic, huh?) meant Prohibition was inevitable but the bill had only just passed Congress, being ratified by the states in January 1919 and coming into force in January 1920.

Exactly one hundred years later we went through a similar process. Brexit was likely unavoidable in 2017 (it would have presumably required revoking Article 50, which would have been punchy), on the legislative docket in 2019 (at first failing under May, then passing under Johnson), and Britain formally left the EU in January 2020.1

I know history repeats but exactly one century apart is good going IMO.

It is now 2023. By my American parallel that means the untimely death of the head of state and the outlawing of teaching evolution, so if we could stop the parallels with the UK now that would be grand. In Prohibition terms, in 1923 the banning of alcohol was in full effect, with tens of thousands of people arrested under the draconian Volstead Act.

But just a couple of years later the first cracks started appearing in the edifice. The journalist HL Mencken claimed in 1925 that Prohibition was failing. The ‘wets’ in Congress slowly re-emerged and began a fight-back against the dominant ‘drys’, with the aid of millionaire industrialists. And Prohibition was repealed in 1933, following FDR and the Democratic Party’s overwhelming electoral victories in 1932.

And what of here? Brexit seems to be faring less well than Prohibition, at least on the parallel history timeline. Public opinion has shifted sharply against the merits of having left since 2021. Britain’s chief political opportunist, Nigel Farage, has already denounced ‘this’ Brexit. And most significantly, public support for the idea of actually reversing Brexit - ‘Rejoining’ - has surged.

And ‘Rejoin’ is the closest parallel to the 21st Amendment, the constitutional amendment that reversed Prohibition. Any time you mention the word ‘Rejoin’, the winged harpies of scold Twitter descend to remind you of the difficulties of doing so, from the likelihood of public opinion turning away from the option in any new referendum or election fought over it, to the unwillingness of the European Union to offer Britain the same deal it left. To which my answer is, I know.

But ending Prohibition was also very difficult - it required thirty-six states to ratify the 21st Amendment (which they did, uniquely, in state ratifying conventions, rather than through legislatures). It was also the only time that an amendment to the US Constitution has been repealed. And it happened just over a decade after Prohibition had been introduced on a huge wave of supportive public opinion.

Politics is about change. Our institutions are of course important - I just wrote a book arguing that point! But existing laws and rules should not forever constrain citizens, who have the right to change their minds, or who may not have had voting rights first time round. If public opinion remains set against Brexit we will need to consider the merits of, and challenges to, a Rejoin movement.

So, what do the parallels with Prohibition teach us? I’m not an expert in early 20th century US politics so I will have to put my comparative politics hat on and say let’s not get too hung up on the specific contingencies of US history and instead look for broader, more generalisable lessons. So in that spirit - here are five lessons from the end of Prohibition, which have remarkable parallels to today and then one anti-lesson, where matters are very different.

Lesson One: Chasing the Car is Better than Catching the Car

The crucial force behind Prohibition was the Anti-Saloon League or ASL. Founded in 1893, it is often thought of as America’s first single-issue pressure group. And boy did that pressure pay off - they focused on localities, turning counties dry; on states - by 1913, there were 9 dry states and by the time of Prohibition, 25 states had gone dry; and eventually on the Federal government itself. Prohibition was passed by almost every state - only New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island held out from ratifying. It’s hard to imagine a more effective pressure group.

But then it won. It could of course still fulminate about enforcement of Prohibition, which it did. But like so many successful pressure groups, once the main goal had been achieved it was hard to keep up momentum. And bootlegging was so successful that it often seemed a Pyhrric victory. The editor of the Hutchison News, in dryer than dry Kansas, remarked in 1930, that “there is ten times as much drinking in Kansas as there was ten years ago” (Okrent, p.334). The law alone could not compel obedience with its goals. Gravity remained.

And worse, the leaders of the dry movement were not always pure-as-snow. Mabel Willebrandt was the second woman ever to be appointed assistant attorney general and was the most senior woman in the Federal government during the 1920s. She was a fierce prosecutor, using the Volstead Act to secure almost forty thousand convictions. She developed the strategy of catching bootleggers on income tax evasion, which ultimately did for Al Capone. And she was so unpopular with ‘wet’ politicians that the Democrat’s candidate for President in 1923, Al Smith, nicknamed her Prohibition Portia. In my deep deep research for this piece I have discovered this means Brutus’ wife Portia, not Portia from Merchant of Venice. Don’t tell me this is not a high-brow Substack.

Willebrandt, like Brutus (see what I did there), had her own moment of treachery. She left government in 1928 and moved to private legal practice. Where her major client was the oddly-named ‘Vine-Glo’. What pray tell was this? A block of condensed grapes that you left in a bucket in your basement to ferment. Mmmm… Tempting I know, but not something one would expect a Prohibitionist to support.

And indeed, Willebrandt was not the only dry to have her iron in multiple fires. The Republican Vice President Charles Curtis was sucked into a bizarre controversy involving bootleggers importing Dutch ‘sheep dip’. Makes Vine-Glo sound appetising. And although the Republicans were the ‘dry’ party, they were not beneath purchasing gallons of ‘sacramental wine’ in the hopes of winning the Jewish vote in New York City in the 1928 election.

Of course, some drys remained loyal to the end of Prohibition. But as their dream faded away they became embittered and paranoid. As Daniel Okrent (p.347) remarks, “drys […] found themselves lining up behind hysterics and haters.” The language used by ASL leaders became ever more extreme. The Reverend Ira Landsmith claimed that the wet movement “was a greater danger than open rebellion” and that wet interest groups were “traitors”. Even once loyal supporters were hounded out - Senator George Norris of Nebraska, a staunch dry Republican, was opposed by the ASL because for economic reasons he supported Democrat Al Smith in the 1928 Election.

By 1931, the ASL had run out of supporters and run out of money - it had to stop buying newspapers and couldn’t pay its staff. Its revenues collapsed by ninety-five percent between 1920 and 1933 (Okrent p.348).

So… interesting and all, but what are the parallels? Here are a few. First, like the temperance movement before Prohibition, there was a long prehistory to Brexit. The Bruges Group and fellow travellers in the Conservative Party had decades of position papers and grassroots rallying to fall back on. The rise of UKIP in the decade before Brexit and the threat they posed to Europhile Conservatives looks like the pressure placed on wet Republicans. And as with Prohibition, once the deed was done, life became substantially harder for the Brexit movement.

One problem Brexiteers have faced is that many people still desire the forbidden fruit - not just trade with Europe but immigrants from Europe to fill gaps in the labour market. Just as drinking ended up surging in supposedly dry Kansas during Prohibition, Brexit has produced a large bump, not collapse, in immigration. Obviously much of that is legal immigration because of the way that the Cummings-era skilled immigration bill worked. But ‘illegal’ immigration - at least as we count it in Channel crossings - has increased, not declined with Brexit. There are still jobs, there is still demand, people still want to move. The rules restrict but cannot entirely compel. Gravity still holds.

And the perceived failure of the revolution, as with Prohibition, has produced anger and cries of betrayal from the backers of Brexit. We are, I think, all quite used to the language of ‘traitors’ and the depiction of opponents to Brexit as engaged in something like ‘open rebellion’. Once loyal Brexiteers - the George Norrises de nos jours - whose loyalty becomes suspect are cast out. The long-time Brexit supporter Rishi Sunak becomes ‘not a proper Brexiteer’.

We see too, the proponents of Brexit sometimes less austerely anti-European in their business deals. To wit, the famous investment advice provided by Jacob Rees-Mogg’s Somerset Capital about the dangers of Hard Brexit. Or John Redwood’s advice to avoid investing in Britain. And then we have the European passports acquired by Brexiteers from Farage to Moylan.

But history rhymes rather than repeats. The financial flows supporting Prohibition dried up over the 1920s. By contrast, Brexit-backing donors like Paul Marshall remain major supporters of pro-Brexit media such as GB News. We have not yet, perhaps never shall, reach the stage of the Bruges Group having to cancel its newspaper subscriptions.

Lesson Two: Show me the Money

It’s all fun and games until the money stops. The 1920s boom and the minimal spending of US states and the Federal government in that era meant that one major financial hit - the end of alcohol taxation because of Prohibition - took a while to be felt. And then 1929 happened. Massive demands for public spending loomed over the horizon, particularly as it became clear that Herbert Hoover’s laissez-faire administration would be replaced by FDR’s New Deal.

And that it turn meant the need for tax revenues. In 1913, the passing of the Sixteenth Amendment enabled Congress to pass income taxes without having to apportion them precisely by states’ populations. Before 1913, around forty percent of revenues came from the taxation of liquor. The creation of an income tax system would allow the government to substitute for that revenue stream and hence facilitated Prohibition.

But you know who doesn’t like income taxation? Everyone. Well, especially people with high incomes. It became very clear to America’s millionaires, particularly the vastly wealthy DuPont family, that they were now the goose whose feathers were being plucked - and with a free-spending Democratic Presidency around the corner, the plucking would intensify. The DuPonts and their allies worked with the AAPA - the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment - as their lobby vehicle, with Pierre DuPont serving as its President from 1927.

DuPont was a wet, he wanted legalised alcohol. But he also had ulterior motives. In 1932, he wrote to his brother “The Repeal of the XVIIIth Amendment would permit Federal taxation in the amount of two billion dollars […] Such taxation would almost eliminate the income taxes corporations and individuals” (Okrent, p333). In other words, the rich were being squeezed in the name of Prohibition and its Repeal would lower their taxes.

Savvy politicians knew that the lure of tax cuts might over-ride the puritanism of the dries. When the Repeal Amendment was passed by Congress and awaited ratification by the state conventions, Congress passed temporary income tax surcharges that would be removed if and when enough states had ratified Repeal. Pierre DuPont might have been a bit over-ambitious in his claims that alcohol duties could provide two billion dollars of revenue but experts in 1933 estimated they would raise around half that (Rorabaugh, Prohibition: A Very Short Introduction, p 105).

And the alcohol industry created far more jobs than enforcing Prohibition - around half a million new jobs would follow Repeal. With the Wall Street Crash leading into the Great Depression, the need for both revenues and jobs was paramount. Economic crisis, not caused by, but perhaps not helped by, Prohibition, was the harbinger of Repeal.

So to today once more. Well, the economy isn’t going great. The UK has massive spending commitments, likely rising in the current inflationary environment (that’s different I guess, the 1930s were deflationary). The current British tax take is its highest for over half a century. And conservatives are upset with their own government for the tax pressure on citizens, including the wealthy.

Sadly, this time I don’t think we will make it up with alcohol duties - not least because we already have them and they are already high. But it is, I think, fair to argue that Brexit has placed stress on the public finances if it has reduced the trend rate in growth, as almost all economic analyses suggest (sorry Patrick, mate, but I don’t buy your claims).

And if a Labour government comes in and squeezes high income / wealth individuals or corporations, you can imagine the pressure rising to look for ways to lower the tax burden. The most obvious one being a good healthy dose of economic growth. Now, supply-siders such as Liz Truss thought that the growth could come from lowering taxes themselves, which would indeed be extremely convenient. But, at least in my view, not hugely consistent with existing economic research. More likely, higher growth allows a loosening of the tax burden if tax revenues are boosted by higher activity. TLDR: grow then cut taxes.

So, is there a group of DuPonts demanding the Repeal of Brexit, not because they are true Remainiacs, but rather in the hope it keeps the tax burden at bay? Hard to tell, because business has been so cautious about criticising Brexit while the Conservatives are in power. But, like Stephen Bush of the FT, I suspect things will change on that dimension post-election. And money talks.

Lesson Three: Uneasy Neighbours

Why was Prohibition so ineffective at actually reducing alcohol consumption? No country is an island. Oh, wait that’s wrong. But the USA is indeed not an island and shares a very very very long border with Canada, where alcohol was still legal during Prohibition. What’s more, until 1930, the Canadians did not restrict exports of alcohol to the US. Indeed, they benefited substantially from export duties that they charged on liquor moving to the US.

The most famous beneficiary of this trade was Seagram’s, the Canadian liquor behemoth headed by Samuel Bronfman, who had founded the Distillers Corporation in 1924 and then bought Seagram’s in 1928. Bronfman masterminded a series of complex and murky trade routes shipping liquor into the US and was rather vague about the financial flows generated when called to Parliament. There was little interest in trying to help the enforcement of Prohibition. The Ottawa Journal remarked that “US Enforcement, like Charity, Should Begin at Home” (Okrent, p343). Other Canadian entrepreneurs were more interested in keeping the US dry, but only to encourage liquor tourism in Canada.

In 1930 the Canadian government finally gave into US pressure and passed the Export Act banning the sale of liquor into countries where it was banned. But Bronfman had a plan. He moved his operations to the French possession of Saint Pierre just outside the Gulf of St Lawrence, using it as a halfway house to import liquor from Canada and then sell it back into the American market. Seagram’s profits were boosted 50 percent by this ingenious scam. It turned out that America’s sovereign right to ban alcohol did not really constrain other countries’ sovereign rights to take advantage of it.

Is the European Union today’s Canada? Northern Ireland today’s St Pierre? Well not quite. But the crucial lesson we can draw from Canada in the 1930s is that business owners and politicians in other countries are not compelled to help you make your policy work.

British investors, like American distillers, can invest or locate their premises abroad, to keep revenues up and access traditional markets. Other countries can take tax advantages of your new laws, even as you lose revenue. Recall that the UK still hasn’t placed trade restrictions on EU imports, even as the EU has happily fulfilled its side of the TCA with British exports.

Clever entrepreneurs will find intermediate locations - a la St Pierre - where they can move goods from market to market avoiding the barriers assembled at the border. Just as America couldn’t rely on Canada to make Prohibition work, the United Kingdom cannot rely on the European Union to make Brexit work.

Lesson Four: People Are Fickle

In 1930, the dry Democratic Senator from Texas, Morris Shepherd, infamously remarked that ‘There’s as much chance of repealing the Eighteenth Amendment as there is for a hummingbird to fly to the planet Mars with the Washington Monument tied to its tail”.

It’s not a great prediction as far as these things go. And the aforementioned scolds of Twitter might want to keep that quote in mind when they announce the impossibility of Rejoin.

Mind you, even the wets in 1930 didn’t seriously consider that Prohibition would end for another decade. Huge obstacles stood in its way. No amendment had ever been overturned. This one had initially been voted through with massive support. Repeal would require getting dry, rural states (whose legislatures were dominated by the driest, most rural counties) to ratify an amendment ending Prohibition.

And yet. The politics of Prohibition completely flipped between the late 1910s and the early 1930s.

In 1918 the US Senate had passed the 18th Amendment introducing Prohibition, 65 for to 20 against, and the House then passed it, 282 for to 128 against. Every state save New York, Rhode Island and Connecticut ratified it.

But… In early 1933, when the 21st Amendment repealing Prohibition came to the Senate, it passed 63 for to 23 against, and then passed the House 289 for to 121 against. And the 36 states needing to ratify the amendment had signed off by the end of the year. Before which FDR had already declared low alcohol beer non-intoxicating and hence legal.

It was essentially a complete reversal in political support among politicians. And this corresponded to a dramatic change in public opinion. To be fair, it’s hard to know how accurate public polling was in this era - probably not very, given the famous Dewey Beats Truman headline a decade later. But in as much as we know anything, the Literary Digest did a mail-in survey in 1932, finding that almost three quarters of the nearly 5 million respondents wanted Repeal. An earlier survey by the same magazine in 1930, the hummingbird year, found a slightly different array of public views - thirty percent backed retaining Prohibition, another thirty percent backed bringing back beer and light wine, and forty percent supported Repeal. Hard Prohibition, Soft Prohibition, and Repeal one might say.

So the public shifted and politicians too. Major dry figures like John D Rockefeller, Harvey Firestone, and Alfred P Sloan Jr flipped. As did the ABA, AFL, veterans organisations and so on. Business, labour, finance, the professions. Each flipped in turn. When Herbert Hoover gave a speech to the American Legion in 1931, he was drowned out by cries of ‘We Want Beer’ (take that Just Stop Oil). Drys started losing to wets in the most unlikely places - even Kansas elected a wet Democrat in 1930. Wets started to win primaries in the traditionally dry Republican Party. There were no safe dry seats or politicians left.

Politicians nervous about the public did waffle - FDR most notably. It took until a surprise announcement that he backed Repeal in his Presidential nomination speech at the Democratic Convention in 1932 for FDR to make his views known. He announced “This convention wants repeal. Your candidate wants repeal. And I am confident that the United States of America wants repeal.” FDR had needed wets to win the nomination and he paid them back. And once he had made his mind up, the Party refused to back candidates who were drys in the 1932 election.

Politicians still felt more comfortable passing the buck back to the people. Hence the importance of state conventions on Repeal, which would allow the exercise of popular voice. It’s hard to know a great deal about individual voting behaviour in 1933, you will not be surprised to hear. But broadly speaking, the kinds of people who voted for Repeal were urban, religious minorities (i.e. Catholics), higher income, and Democrats. Ultimately the national popular vote across state conventions for Repeal was 73 percent. Pretty good job Literary Digest!

I think the change in public opinion is where the parallels with Brexit are probably strongest. If anything the public tide has turned faster against Brexit than it did with Prohibition. Below is a chart from UKICE/Redfield and Wilton about support for Rejoining in a referendum. Over the course of the past year, this has shifted quite starkly in the Rejoin direction. YouGov find a similar gap - with Rejoin currently leading Stay Out by around twenty points, once don’t knows are excluded.

So on the one hand, there has been a tangible shift in public sentiment. On the other, like a nation of hummingbird-fanciers, people don’t seem to think Rejoin will actually happen, even if they might vote for it given the chance. Below is a recent poll from YouGov that shows only a third of people think Rejoin is likely in the next TWO decades. Almost half think it unlikely.

Wets were in the same situation in 1930 - public opinion was shifting due to discontent. But actual Repeal? Seemed very unlikely. And yet.

Another parallel is politicians wanting to play both sides - an experience that Labour watchers will recognise. FDR cavilled and vacillated until 1932. It took the public turfing out drys to change minds. Often in unlikely Kansas-esque locations. So the question is, are by-election losses for the Conservatives in Tiverton or North Shropshire, and council collapses in Surrey and Oxfordshire, the equivalent of Kansas? Or do these just reflect discontent with the Conservatives, not their project of Brexit?

There are also some neat similarities with the base for Repeal and the base for Rejoin - a coalition of the rich and urban with minorities - and very much concentrated among supporters of the main centre-left party. What it this base lacks of course is a leader… but we will get to that.

Lesson Five: What Comes After is Not What Came Before

The final parallel is a ‘be careful what you wish for’ one. The Twitter scolds of lore are fond of reminding Rejoiners that the European Union that Britain left would not be the one it rejoins. For two reasons.

First, in Britain’s absence the European Union has already shifted in a more pro-federal direction that in the counterfactual Remain world might not have occurred. We can see this in the post-COVID €2 trillion Recovery Plan, for example.

Second, Britain in the European Union had a wide array of ‘opt-outs’ - from the Euro, from the Schengen zone, from various security measures, and from the Charter of Fundamental Rights - along with its rebate. As a ‘new’ member, Britain would have to adopt the whole acquis, like any other applicant. Now, colour me slightly unconvinced that this would in fact happen. My guess is a rejoining Britain would not in fact join the Euro and other countries wouldn’t push for that. But it also beggars belief to imagine the deal could be as asymmetric as before.

So it can’t happen right? Well, not so fast. The world of Repeal, after all, didn’t look that much like the world pre-Prohibition. Indeed, it included signing up for a whole new series of regulations and rules that might have seemed draconian in 1916.

The 21st Amendment looked concise, with just three simple clauses. The first repealed the original 18th Amendment introducing Prohibition, the third noted the time scale for ratification. But, the second is more interesting. It banned transportation of liquor into, or consumption in, any States, territories, or possessions of the US that banned alcohol. This clause has been the basis for all the byzantine and disparate alcohol regulations that remain in America - and explains why a number of states stayed dry for decades - Kansas for example banned public bars until 1987. So in fact, the 21st Amendment may have re-legalized alcohol in America but it did so in a way that created quite a distinct legal landscape to pre-1920.

Indeed, making things legal might make them harder to get! Okrent argues that the “central irony of Repeal […] across most of the country, the Twenty-First Amendment made it harder, not easier, to get a drink.” Now there were age-limits, Sunday closing, codes on what types of liquor could be served and where it could be purchased, often even in those states that were libertine pre-Prohibition. In fact, regulation spilled over into issues only related to alcohol. States used post-Prohibition regulation of bars to ban nude performances. New York used them to block Billie Holiday from performing.

A Britain that Rejoined might experience a similar tightening. For example, joining the Single Market once more and reviving freedom of movement for EU nationals could be accompanied by new and harsher restrictions on non-EU migrants, along the lines that are common among EU nations. Immigration could decrease rather than increase. And while Rejoin would enable some freedoms - the Four Freedoms of the single market to be precise - it would clearly mean signing back up for restrictive EU regulations in agriculture, AI, etc.

Britain could absolutely end up in a. more regulated environment than pre-2016. Of course that’s reason for Brexiteers to oppose it. But, it’s also possible that there will be more demand from the British public for Europe-style ‘protections’ than some think. Certainly, my experience today with the new Threads app makes me wish that, like EU residents, I had been blocked from using it.

Anti-Lesson One: You Need a Leader

There is one particular place where I don’t think there is a useful parallel with Repeal and that’s the role of leadership. At least as yet.

Now this one is a bit tricky. I am presuming that if there were to be a pro-Rejoin leader of one of the big two parties it would be Keir Starmer. I know the Conservatives are inveterate and impressive shape-shifters but that pivot seems beyond even them. But Keir Starmer has expressed absolutely zero interest in hinting at Rejoin. Indeed, New Starmer is all about Making Brexit Work. As opposed to Old Starmer of 2019, who seemed oddly unconvinced of Brexit’s merits. Who can blame him for changing his mind, given the myriad successes of Brexit electoral incentives he faces. And I doubt this post (hi Keir!) is going to change his mind.

FDR also held out a long time to be fair. Until 1932, even though dries had lost plenty of seats in 1930. Part of the reason might have been personal - Eleanor Roosevelt was a very active dry. But I suspect it was good political timing - wait for the wave to crest and surf at that exact moment.

There are some important differences in internal party politics too. Whereas FDR needed wets to win the nomination in 1932, Starmer in 2019 needed to convince the Corbyn Left - including lots of Lexiteers - that he was one of them. The pro-Rejoin faction of the Labour Party have not been able (and likely will not be able) to discipline the leader in a European direction. And discipline works both ways - FDR’s campaign managers withdrew funding from dries in the 1932 election. It seems unlikely to me that Starmer will do similarly to anti-EU MPs, not least because that is Starmer’s own (current) position!

Once FDR had changed tack and become a wet, he did one thing I suspect will be a long time coming for Labour - he made an explicitly positive case for Repeal. A classic hindsight-is-perfect argument about Brexit was that Remain failed because it didn't make a positive case for the European Union. I am unconvinced that a happy clappy blue-and-yellow-stars campaign would have worked but I take the point.

FDR had a singular positive mission - to save America from the Depression. And Repeal was a key weapon in that arsenal. It would boost employment in the distillery and hospitality industries, it would generate tax revenues, and frankly it gave Americans something to look forward to.

A successful Rejoin campaign would need, I think, to be placed as part of a broader national mission. A mission to regenerate Britain’s social fabric, its fraying public services, its anaemic growth. How European Union membership would help in that challenge would be a crucial part of any Rejoin narrative. And as yet, Labour’s ability to sell a clear positive narrative to the electorate is I think open to question. I don’t really see Rejoin being bolted on to the national mission of a charismatic political entrepreneur at this juncture.

The Conditions for Rejoin

So, Ben, is Britain actually going to Rejoin the European Union? Ah… First rule of political science is don’t make point predictions. So I will remain suitably gnomic.

What I hope I’ve accomplished with this post - other than taking down your email accounts with a magnum opus - is to give a sense of what mattered in a comparable-ish case where a major political decision was made, turned out less positively than expected, and was then repealed. I think there are a few ingredients that make a Repeal / Rejoin.

First, you need the status quo to broadly appear to be failing and for its supporters to be despondent, desperate or paranoid. Check.

Second, you need an economic crisis that forces you to re-open dormant markets and promises a bump in tax revenues. Check.

Third, you need a major change in public opinion, that manifests in politicians associated with the status quo policy losing office en masse. Check now (by-elections and local elections) and likely in the future (General Election).

And fourth, you need the leader of a major political party to back changing horses; to do so publicly and definitively; and to punish members of their party who disagree. Yeh, not so much.

Still, call me back in 2033.

If you enjoyed today’s post, you’ll be delighted to know I have a book out. Why Politics Fails was selected as an ‘unmissable’ politics book in Waterstones’ April monthly newsletter. So, don’t miss it! You can order from Waterstones here. Or a signed copy from Topping here. Or at the behemoth here. North Americans head here.

And if you don’t subscribe - my Substack is free so please click below.

Brexit did not actually come into proper force until mid 2021, when the Trade and Cooperation Act was applied fully (with some parts, particularly Britain’s import checks still not actually operating even at this point).

I think if we are to get the economic growth we need, we will need to join, or become an associate of, the EEA single market. I doubt we will ever rejoin, sadly. Our political parties are too scared of the media reaction. If we got electoral reform, a stable majority coalition might be bolder.

I loved the history of prohibition analogy. The GOP certainly seem to like going down these dogmatic cul de sacs.

Hi Ben I would love to have you on my show some time if you would be up for it