The Red Tightrope

Labour are in a stronger electoral position than it might appear but their red lines may end up hurting them

Lots of things to announce today. First off, and most immediately urgent, my new show Rethink drops on BBC Radio 4 at 4pm UK time today (as in a few minutes from now!). Fear not if you failed to read this email immediately on sending - it will be available on BBC Sounds for your nonlinear listening pleasure. The first episode is on internet enshittification, which somehow, I managed to convince Radio 4 that we could say pre-watershed. Wish. Me. Luck. The episode has an interview with Cory Doctorow and a panel with Gina Neff, Marie Le Conte, and Cristina Caffara. It is, as the kids say, a banger.

But there’s more! This week’s What’s Wrong With Democracy? has us focus on corruption with my Nuffield colleague Ezequiel Gonzalez Ocantos and the FT columnist Simon Kuper. We’ll discuss, among other things, whether British politicians are particularly prone to wanting to live the lives of the rich and famous by, oh I don’t know, accepting freebies…

And yes there’s even more! Because the app is back. What app you say? Read on

I am about to do something dangerous, which is to annoy the FT’s Stephen Bush, who has been arguing on BlueSky (possibly also at the bad place) that too many people are focusing on the possible precocity of the incumbent Labour government’s polling position. Stephen rightly notes that the next election is five years away - a LOOOONG time - and that perhaps we might spend our time better discussing the policy challenges that the government is facing right now. I agree, that would probably be a more wholesome use of our time.

But the thing is, I have an election app. And I just updated it to reflect the election held a couple of months back. And I must let the app speak. So, Stephen, sorry.

In part I’m writing this in response to recent interventions by Peter Kellner and James Kanagasooriam, the latter of whom coined the ‘sandcastle’ theory of Labour’s victory. The idea is that Labour’s huge parliamentary majority of two thirds hangs on a rather thin plurality of votes of cast of one third. Labour barely got a higher percentage of the vote this time around than in 2019. But from 200 odd seats it now has over 400. What an electoral system! <chef’s kiss>

Sandcastles are notoriously prone to the tide coming in, washing away their flimsy bulwarks (although filling the hard-dug moats in the sand very satisfactorily, IMO). The idea is that Labour’s victory is very marginal. That small shifts in the vote could fatally undermine their position in Westminster. That’s what I thought too.

But not so fast. Because 2024’s Election was so fundamentally split, with the Conservatives also flatlining, it’s not actually clear that small changes in Labour’s vote share really will have that effect, as we shall see. It will basically require a much much stronger Conservative comeback than currently looks on the cards to take the sandcastle down. But… and we’ll come to this, if Britain’s economy and public services continue to degrade - in part because of Labour’s ‘red lines’ over both taxation and Europe, that’s exactly what might happen. The red lines mean that Labour could be walking a red tightrope to the next election. Let’s find out why.

Return of the App

Regular readers will know about my election prediction app. I would say it did ‘OK’ with the pre-July 2024 election polls in figuring out what the new Parliament would look like, though like many other estimates, the app under-predicted the Conservatives and over-predicted Labour seats (it did well with the Lib Dems though). This was mostly an issue with the polls under-estimating the Conservative vote and overestimating the Labour one - so garbage in, garbage out.

But now we have the real 2024 results we can go again! The nice thing about the app is it gives a useful baseline in terms of how votes convert into seats in any given Parliament. So first off, why don’t you click through to the new app right now and have a look. It is of course named the 2029 Predictor App because that’s when the next election is most likely to be.

Regular users will know there’s lots of things you can do with the app. Most simply you can see how changes in national vote numbers convert into seats given the last election, using either a Uniform National Swing or Proportional Swing assumption - more on this momentarily.

You can also twiddle various knobs and see what happens when there is more tactical voting - shifting Labour, Lib Dem and Green voters to each others’ candidates or shifting Reform voters to the Conservatives.

And then with all this in hand you can plot the expected outcomes on a map or against various demographic characteristics at the constituency level, or see which the most marginal seats are, or download all the data. Lots of buttons for you to press.

But I’ll keep it simple here. How does Labour’s victory compare to what might happen under current polling - whether that’s really meaningful in any way (don’t shoot me Stephen) - and to more extreme examples of recovery for the Conservative Party? When I began re-working the app, I’ll be honest, I thought things would be very precarious for Labour. But! That’s not the case at all. And that is a political fact really worth getting our heads around and the kind of thing you really need an app to simulate, IMO.

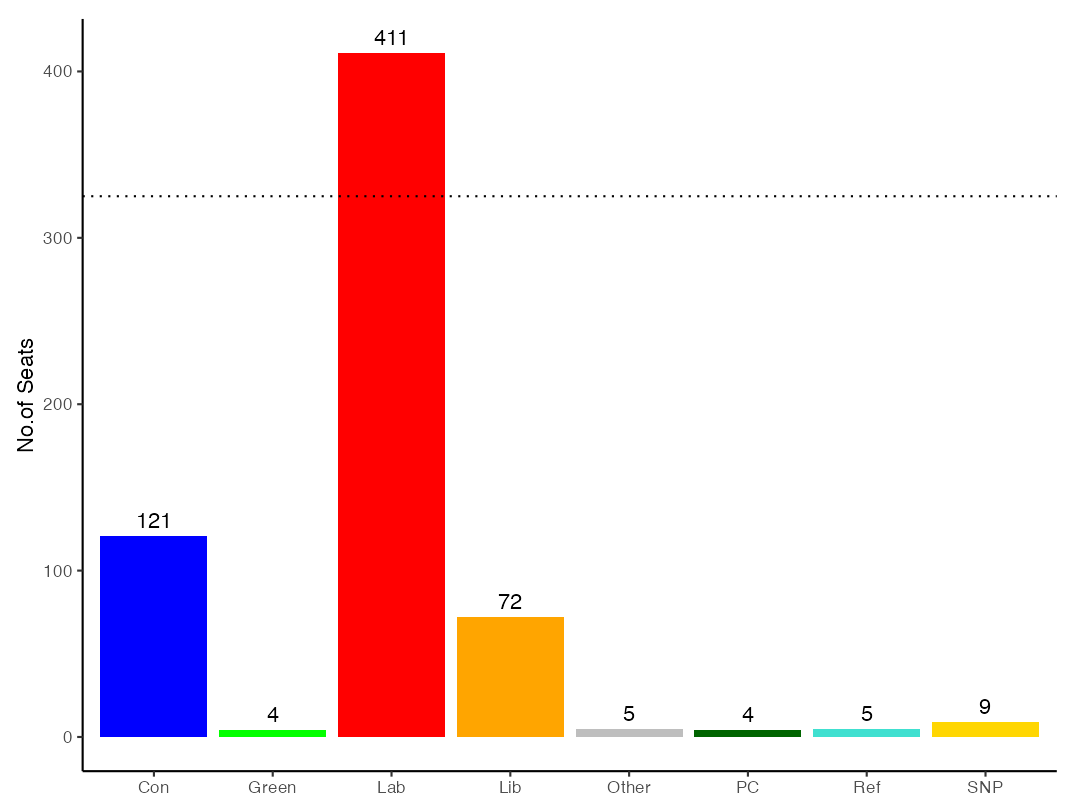

So, here is the current split in Westminster, which my app spits out when you load it up or refresh it and reflects the GB only polling (i.e. I take the actual UK wide results and adjust it to remove the Northern Irish share plus that going to the Speaker, and recalculate each party’s average). So this is Westminster as of July 5th. The adjusted results are L 34.6, C 24.3, LD 12.5, Reform 14.7, Greens 6.7, SNP 2.6, Plaid 0.7.

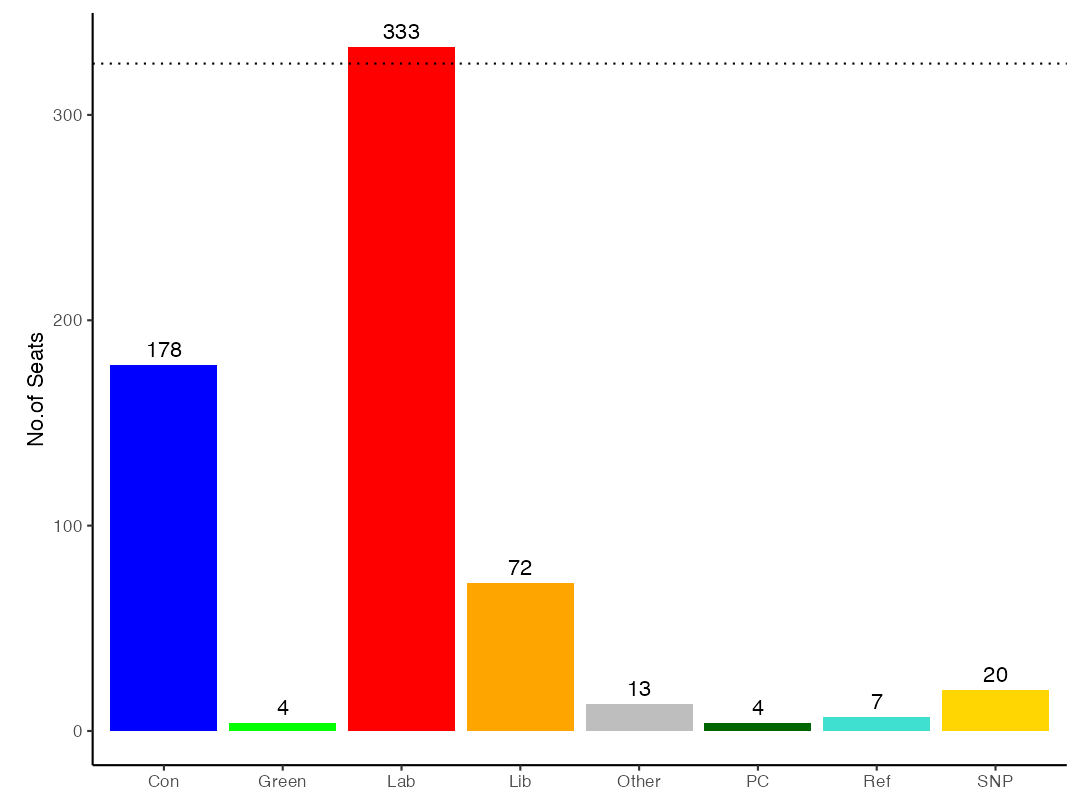

Recently the think tank More in Common released a voting intention poll that showed L 29, C 25, LD 14, Ref 18, G 8, SNP 3, PC 1. So basically Labour losing about six points to everyone else. That’s bad right? I mean it’s not great but here is what my app says is the likely result, assuming that swing is proportional for Labour and the Conservatives (which as we shall see fits 2024 well). Labour still have a smallish majority. And the Conservatives are miles away from a comeback. Largely because the small parties are mostly unaffected (except the SNP who have a jump up).

Do I think it’s great to have an electoral system where a party with under 30 percent of the vote can have a majority. No. That’s bad. But it is the system we have.

Now let’s assume that Labour will not in fact collapse to under 30 percent of the vote - which does seem quite harsh. And instead let’s imagine the Conservative Party makes a comeback. Right now they are going through a leadership election so interminable it makes Game of Thrones seem perfunctory. It may even end up being bloodier. But at the heart of this Blue Wedding is a decision for the Conservatives to make: go right and try to win back the hearts of Reform voters, or go left and appeal to Liberal Democrats.

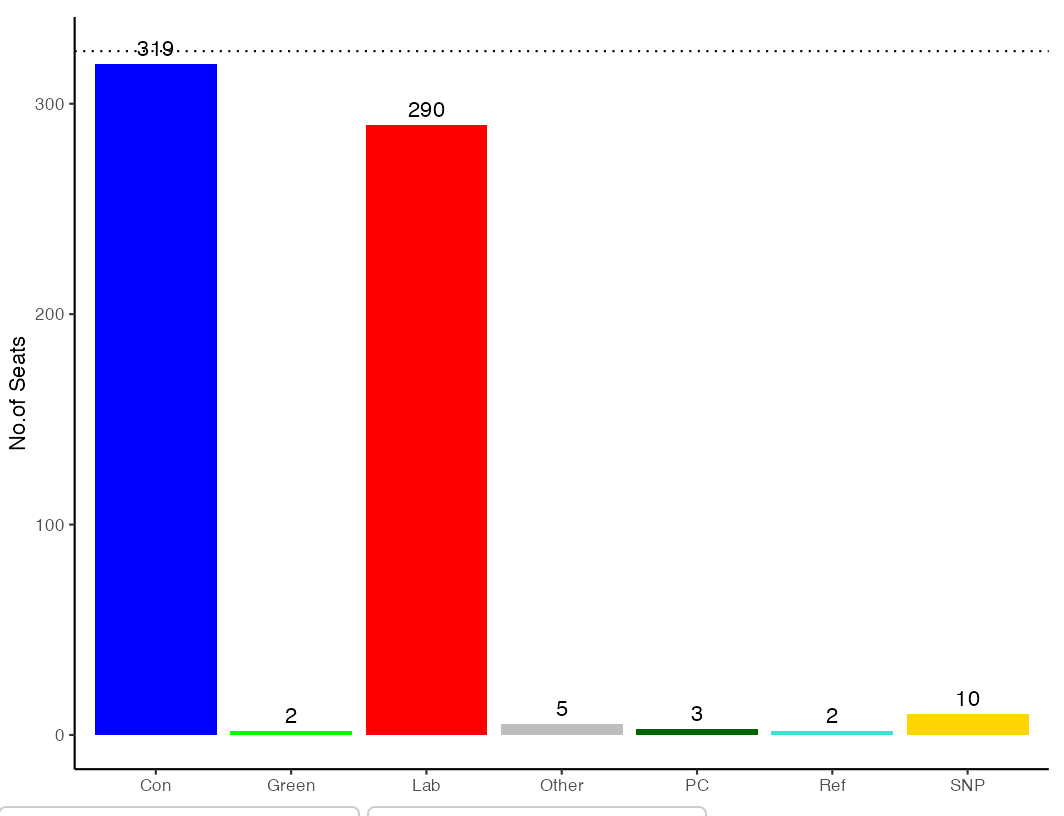

Let’s see what happens if Labour stay stable at their 2024 34.6% of the GB vote but we assign ALL Reform UK voters to the Conservatives.

Oh… We end up with a hung parliament. Albeit without Nigel Farage in Westminster, so I suppose there’s that. In fact, you know what this looks very much like? 2010. So Ed Davey and Kemi Badenoch strolling hand in hand through the rose garden… You can see why this might not, in fact, work. But Labour also can’t form a majority, even with a coalition with Ed Davey. Even the Northern Irish parties - excluded from the graph above - aren’t going to help. So, basically who knows? It would be febrile and mad.

What about the alternative Tory strategy - the 2015 model where you eat the Lib Dems alive? To get this I did something very funny to my model which is set the Lib Dem vote to -100. The thrill of it. Because the Lib Dems are always modelled using UNS, I need to do this to remove all their seats. Anyway, here’s what you get.

Another hung parliament! However, this is one that might just work for the Conservatives because it looks rather like 2017, except with Labour doing better and the SNP worse. Another deal with the DUP in the offing!

A few things to note then. First off, I don’t fully follow the Jenrick / Badenoch philosophy of veering right because, as we see above, you are better off as the Tories winning all of the 12.5% of Lib Dem voters than you are winning all of the 14.7% of Reform voters. That is, of course, because the Lib Dems have lots more seats that you could win off them.

Second, even in these extreme scenarios, Labour is still hovering there or thereabouts. And I have allowed for no tactical voting among centre-left voters here.

So broadly speaking, I think the Conservatives are in a worse position than the current media consensus has them, and Labour in a better position. And really that should not be surprising, given that the Conservatives had THEIR WORST RESULT EVER.

The thing we all need to remember from the 2024 election is that it superimposed the kind of voting patterns you regularly see in European countries with proportional representation on top of an FPTP electoral system that spits on the do-gooding representativeness of PR. Here is what a Dutch style PR electoral system would have produced from the voting outcomes of the 2024 election. Schmooth.

In the current Parliament, Labour are in the catbird seat - what was implicit but I didn't say out loud in the graphs above is that even when I gave the Conservatives a moderate to large lead on Labour by adding 12.5 or 14.7 to the Conservative vote, they still couldn’t get a majority.

Swingers

But but but. Here’s why I am a little less confident than my app. The last election was super-swingy. Not just in terms of the enormous loss that the Conservative Party experienced but in the way that played out.

Now here’s the boring technical bit. There is a longstanding debate, that I have previously written about on this Substack - when parties lose or gain votes does that happen in the same way across all constituencies (so if you lose ten points in national vote you can uniformly subtract that from each constituency) or do you lose more votes where you had more to begin with (so that the size of the loss is proportional to the initial vote share)? In other words do we have Uniform National Swing or Proportional Swing?

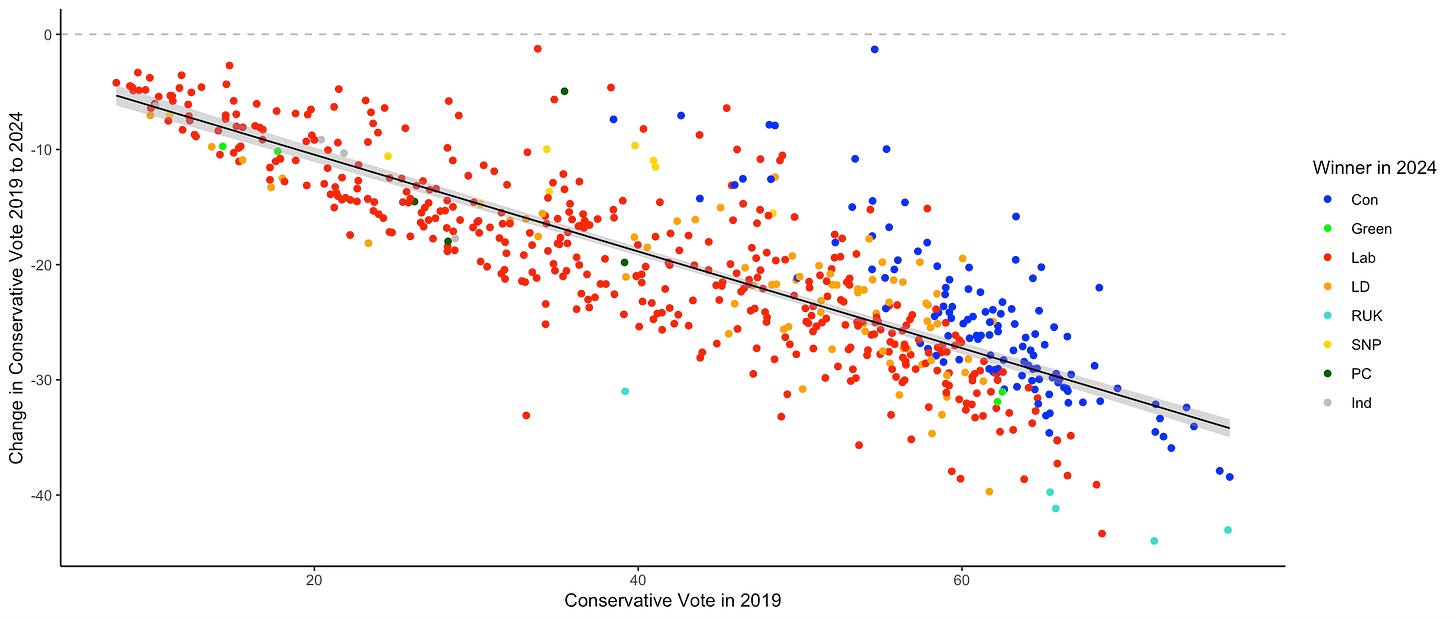

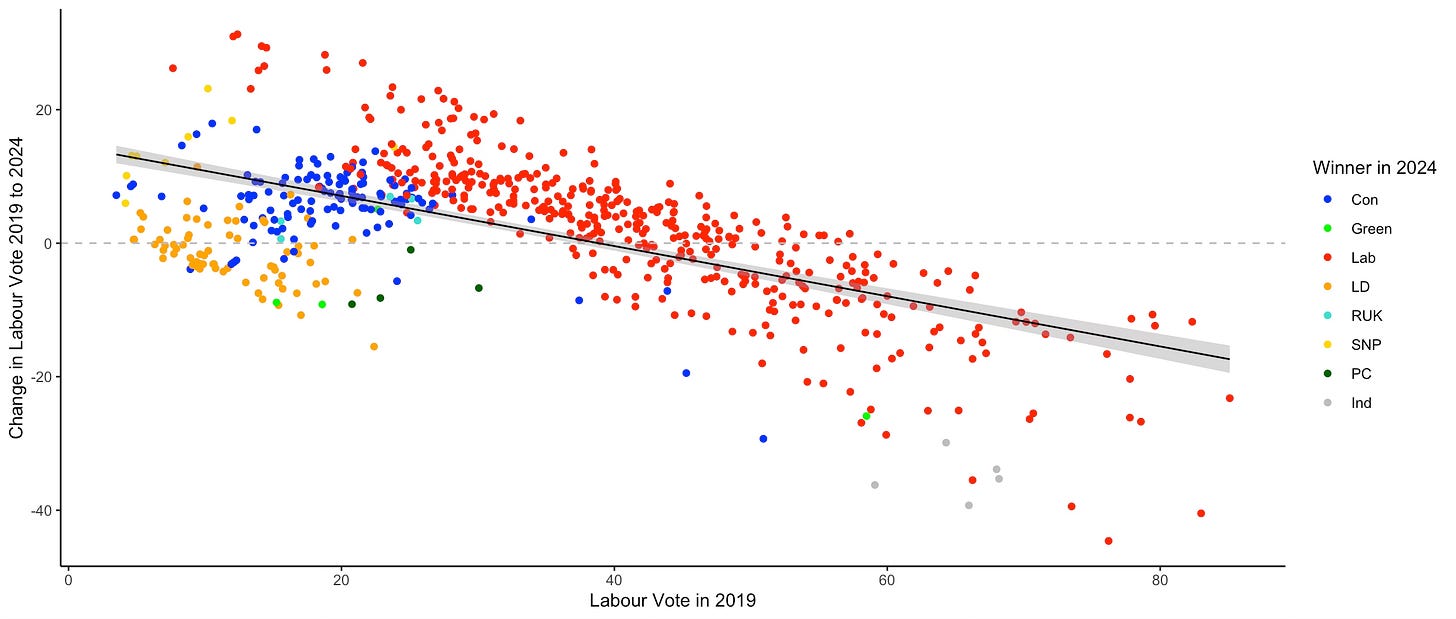

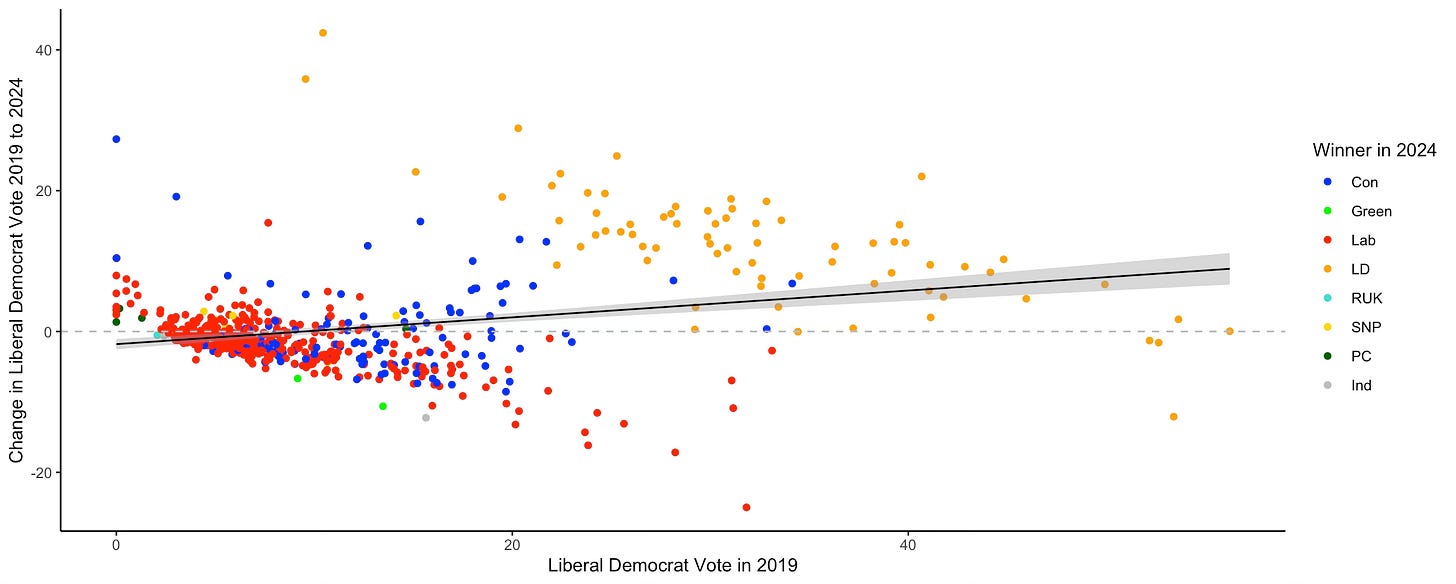

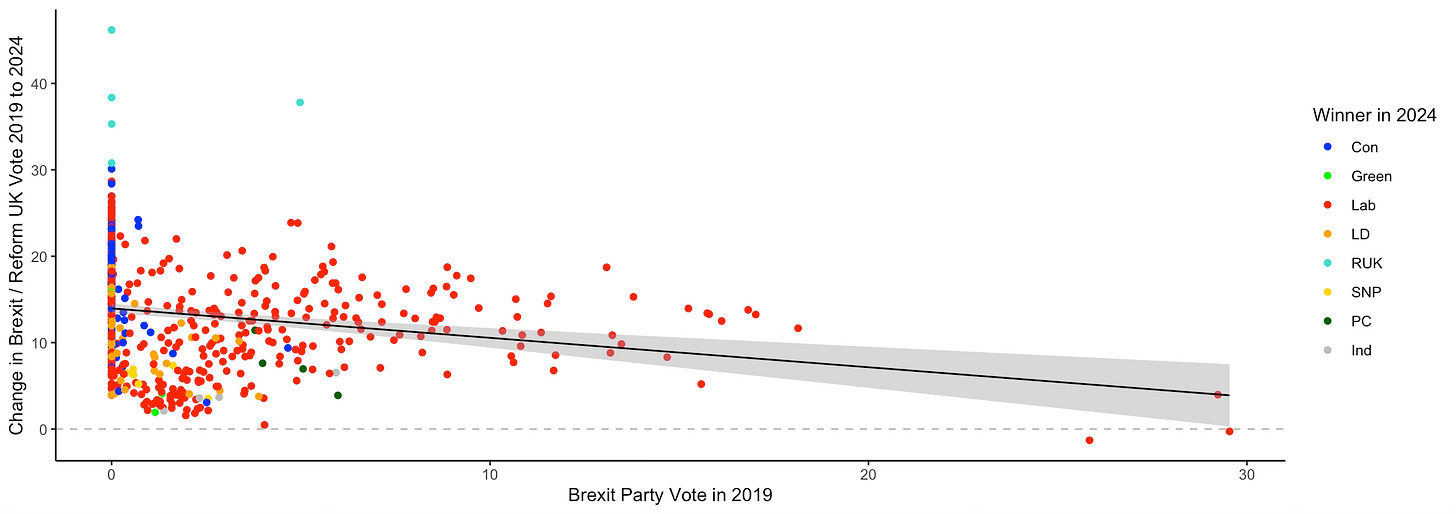

The easiest way to check is when an election has happened. You can then simply plot the previous vote share against the change in vote share. If it’s a flat line - that is, if the change is the same no matter what the initial vote share was - then you have UNS. But if the line is negatively sloping, then things are proportional.

Here is what we see with the Conservative Party. This is pretty dang proportional!

When the Conservatives had around sixty percent of the 2019 vote they lost around 25% whereas when they had about thirty percent of the vote they lost about 12.5%. The overall decline in Conservative vote share across the election of just under twenty percent points, comes more from where they were doing well. Or equivalently, they lost just under half of the vote they had in most constituencies.

What about Labour?

OK this is weird. The thing is, Labour didn’t swing in the opposite direction. Recall they only gained a couple of percent in the national vote. And they did that by losing votes where they had lots already and gaining where they didn’t. And that turned 200 odd seats into 400. Wild stuff! This is the efficient strategy at work. In any case, there is a negative slope here and some proportionality.

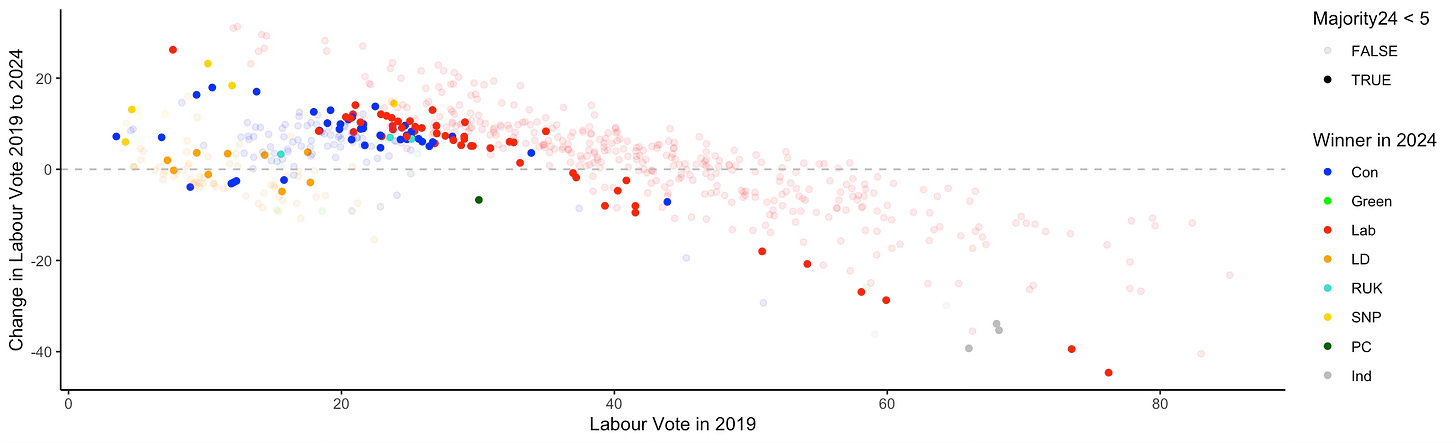

But it does suggest some inherent challenges. If we just look at marginal seats in the graph below (seats with under five percent margin are highlighted) we see that yes there are a bunch of Labour seats that it just won, having started with high 20s or low 30s of the vote. But there are also a bunch of really marginal seats that should be safe Labour (and indeed this is where Independent candidates won 5 seats off them). So there’s a risk for Labour in focusing on classic swing seats - that they keep losing votes in safe areas - we’ll come back to that.

What about the smaller parties? With the Lib Dems and Reform it’s a little tricky because both are obviously much stronger in a smaller number of constituencies - so don’t read too much into the slopes of the fitted lines. To me, to be honest this actually looks like a fairly flat relationship but one where the Lib Dems actually gained most where they were already strong - the Mark Pack master targeting strategy - and where Reform pulled back from where they (well the Brexit Party) were strongest in 2019, largely because the Brexit Party famously didn't stand in Conservative seats then.

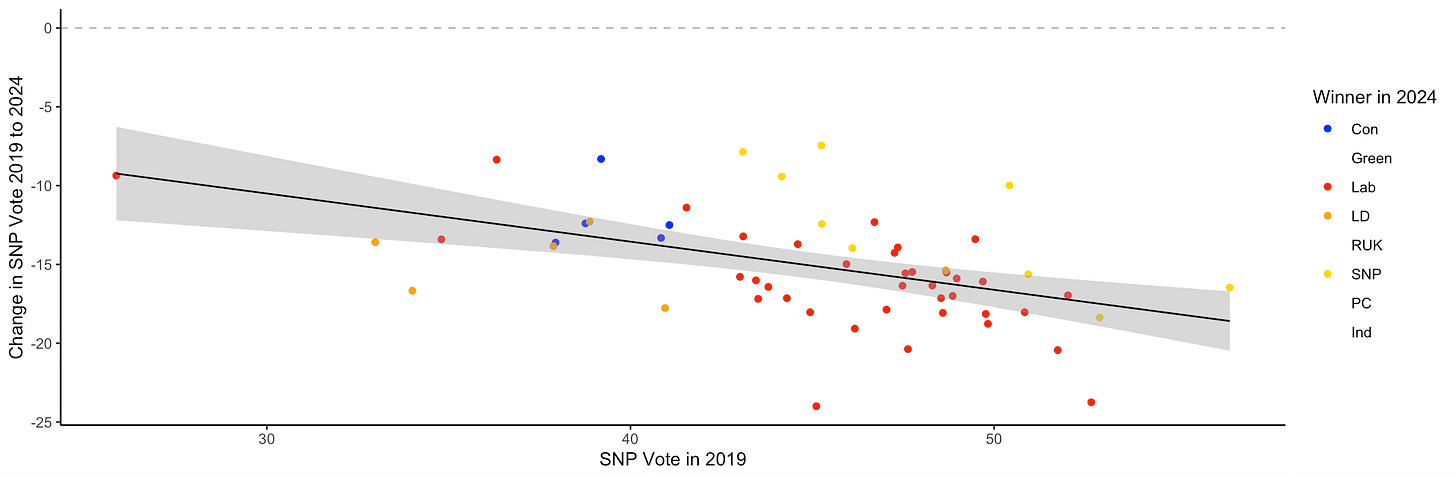

Finally, here’s the SNP. I actually expected this to be a much steeper line but actually UNS is not a terrible fit here. It was fairly universally rubbish performance for them.

The End of the Education Divide

Before I come to some final thoughts about Labour, I hope you will bear with me for four more graphs. We have got used to talking at great length about the educational divide in British elections, where in 2019 the Conservatives dominated among people with fewer educational qualifications and Labour with those with degrees. Actually when you cast out to constituency level it was never that strong a relationship. But, now? There is no relationship at all. The Conservatives, it’s true, don’t have many seats with lots of people with degrees - but there’s no relationship at all between degree-holding at the constituency level and the Conservative vote.

And that’s also true for Labour! Labour has lots of seats without many graduates and lots of seats full of graduates. War is over! The educational divide has been healed!

Well almost… Because it’s still there among the smaller parties. Here are the Lib Dems. A strong positive relationship with graduate numbers and Lib Dem votes. Ten percent more grads gets you about five percent more Liberal voters.

And then there’s Reform UK. Loooooool. Yeh that’s a tight fit. In places where only twenty percent of people are grads, Reform were getting over 25% of the vote. Just look at their five seats in the top left of the graph. Where over fifty percent were grads, they were getting under 10% of the vote. It’s not quite a one to one relationship but it ain’t far off. So good luck to Nige winning Oxford West and Abingdon.

Red Lines to Red Tightrope

And so to some broader policy conclusions (see, Stephen, I’m trying!). First off, I think it’s a good thing the educational divide is weakening. I don’t think it was good for creating a sense of common solidarity. And frankly I also don’t think it was good for universities. But it does feel to me that a Conservative Party that goes on a dash for Reform might end up leaning ever more into uni-bashing - a skillset they have been assiduously developing for the past five years. Similarly were I the Lib Dems I would be leaning into my ‘party of the graduates’ brand since demographically grads will be an ever larger proportion.

But I want to come as I promised to Labour’s ‘red lines’. Labour have promised not to raise income taxes, NI, or VAT - the three ways that you might easily raise taxes. Instead they seem to be proceeding with a plan to hike lots of smaller taxes that affect specific groups. I fear that plucking lots of small feathers one after the other will offend the goose more than hoiking out one big feather quickly, but that’s the choice they made.

Beyond the political risk of lots of mini taxes that produce a death by a thousand cuts, there is also the risk that small taxes won’t add up to big revenues (and indeed some might have growth-harming incidence effects). And if that’s the case, Labour won’t be able to fix public services. And if that is the case, Labour will be in real trouble for the next election. Yes, the Conservatives have royally screwed up in the past election - in such a manner that even taking ALL the Reform voters back or ALL the Lib Dem voters back still can’t get them into a majority. That is a stunning failure. Well done lads.

But we saw above that Labour have already lost lots of support where they were already most popular - to me, that is a very dangerous sign for the future because once it’s gone, it may not come back. See the socialist parties of France, Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, and maybe Germany, for reference. In European countries with multi-party systems, disaffected left-wing voters flock to the Greens or urban liberal parties. And that’s basically what already happened to Labour this election - they were saved by the electoral system. Similarly right-wing populist voters go to those parties. The last decade of British politics has been a story of the Conservatives madly trying to plug up their leak to the right. There is nothing preventing the next decade being the reverse story of Labour trying to shore up losses to their left (or of centrist graduates to the Lib Dems).

And so red lines over taxation might lose voters to the Greens and left-leaning independents. And red lines over the Single Market and Customs Union risks losing graduates to the Lib Dems. And that’s Labour’s main coalition! If it gets stuck only holding constituencies it marginally won off the Conservatives this year it’s in real trouble. Just as flirting with the Red Wall and forgetting the Tory Shires killed the Conservatives. Labour will have to walk carefully along this red tightrope.

So I began by noting there’s a current debate about whether we should ignore electoral politics for five years and focus on policy instead. I don’t think they are, or can be, disconnected. I think the policy decisions Labour makes - has made - will be about securing their new base. I fear for them that those same policy decisions might lose their old base. Labour will have to make choices over policy that will ultimately be choices about where they lose or win votes and seats. But you know what’s good news? There’s an app for that.

A very interesting read; thank you! Though I should add that if you're going to put one name on our targeting strategy, it's much more Dave McCobb than me.

Presumably the pre Coalition LDs were also very grad centric, at least in the cities.