Video games and I go back a long way. In the early 1980s I was a third generation Sinclair power user, which doesn’t really seem like it should be possible. But while seven year old me was reading Crash and Sinclair User, I was following a family tradition. Indeed, my grandfather Eric, a retired shipwright from Cowes on the Isle of Wight, was a Sinclair mini-celebrity. Below is one of my favourite family photos - my grandad on the front cover of Sinclair User in 1983, holding a birthday cake in the shape of a ZX Spectrum.

All of which is to say that ‘gamification’ is a bit of a family tradition. Born in 1977, I’ve had a personal computer or console in the house since my very first memories. I think that makes me not atypical for a young Gen Xer and certainly not for a ‘geriatric millennial’, to use the delightful term employed to describe those a few years younger than me.

And of course as a late forty something I am now old enough to be part of the generation currently running the show in many countries. I have already had to deal with a British Prime Minister younger than me - thanks for nothing, Rishi - along with a French President and Irish Prime Minister. Terrible stuff. Should be banned.

Silicon Valley has always been youthful and so even more unsurprisingly, whole swathes of tech billionaires are younger than me, which perhaps explains their terrible music taste. These titans of our postindustrial world also grew up in a gamified world, ears ringing to the sounds of the Super Mario Bros theme. And people a little older than me would have been at arcades in the late 1970s and early 1980s so perhaps the legions of the gamified can be traced even earlier.

Something then we all share - at least those of us who were Nintendo-pilled - is a great swathe of our leisure time (possibly also studying time) devoted to the particular infernal logic of the video game. Early video games had a particularly linear structure. Platform games required you to complete fiendishly difficult rooms in a precise order. Shoot-em-ups forced you to decimate fixed waves of enemies.

But even non-linear games - the sandbox games that emerged in the early twenty-first century - had an underlying linearity in that progress, however exactly it was completed, was ultimately measured on a single dimension, often captured in three simple letters: EXP.

Your ‘experience points’, or equivalent (money in GTA, levelling up in Dark Souls etc), defined how powerful you were in the late game. Progress through the game could ultimately be boiled down to a simple numeric quantity. A quantity that made once strong enemies weak; that made once-challenging areas of the game a cakewalk; that reflected the gamer’s prowess, skills, and ability to follow the rules of the game.

Wouldn’t it be convenient were life itself so simple?

Apparently a lot of people - sorry, I meant men - think so.

It won’t have escaped anyone’s attention that Silicon Valley billionaires have garnered enormous political power in recent months. Which is not to say they were not massively powerful beforehand. It just… well it didn’t quite feel like it to some of them. Because their gargantuan wealth did not translate into the respect they felt was their due.

You see the problem is that you can accrue unprecedented riches and people can still be mean to you on Twitter. Your employees can still insist that if you sexually harass someone you can be fired. Or that you moderate your language around the workplace. And your kid still might not get into Stanford or Harvard.

But how can this be? You have levelled all the way up, right? You’re in New Game Plus Plus Plus. What else could you have done? Did you miss a hidden chest that had some kind of Godkilling weapon?

And worse, there are all these newbs - no let’s be real about it, NPCs - out there mocking you on social media. Achievement very much not unlocked.

I barely need to name the examples of this kind of surly winnerdom. Elon Musk bought a whole social network and he still couldn’t make it love him.

The venture capitalist Marc Andreessen argued about new Zennial hires that “They’re professional activists in their own minds, first and foremost. And it just turns out the way to exercise professional activism right now, most effectively, is to go and destroy a company from the inside.” His techno-optimist manifesto has an intriguing enemies list, including Friederich Nietzsche’s “Last Man”.

A fascinating article in Semafor about their group chats shows how infuriated the tech elite had become with liberal conventions and elites over the past few decades. And that despite a self-declared love of free speech, many of them had a tendency to simply quit the group chat when faced with someone opposing their consensus that Trump was the saviour of Western Civ.

Reading between the lines, a lot of very wealthy people who talk big game about the ‘battle of ideas’ do not in fact like their ideas to be challenged, especially not by pointy-heads such as me and my academic colleagues. After all, we haven’t accumulated the EXP - sorry money - that should make you important and deserving of being listened to and convinced by.

This disbelief among the Silicon Valley elite that money cannot buy you respect or ideological obedience is a distilled version of a much wider set of beliefs you can find people holding on social media - that there is one way of succeeding in life - some combination of money, muscle, and coding skills. Do you even for-loop bro?

The meme of the week is a twitter thread about British singer Olly Murs, famous among most people for rocketing to stardom through the British X-Factor, though famous to me for live-tweeting phantom gun shots in the storied British department store, Selfridges. Shame they don’t actually, as the old joke goes, sell fridges, since then he could have hid in one.

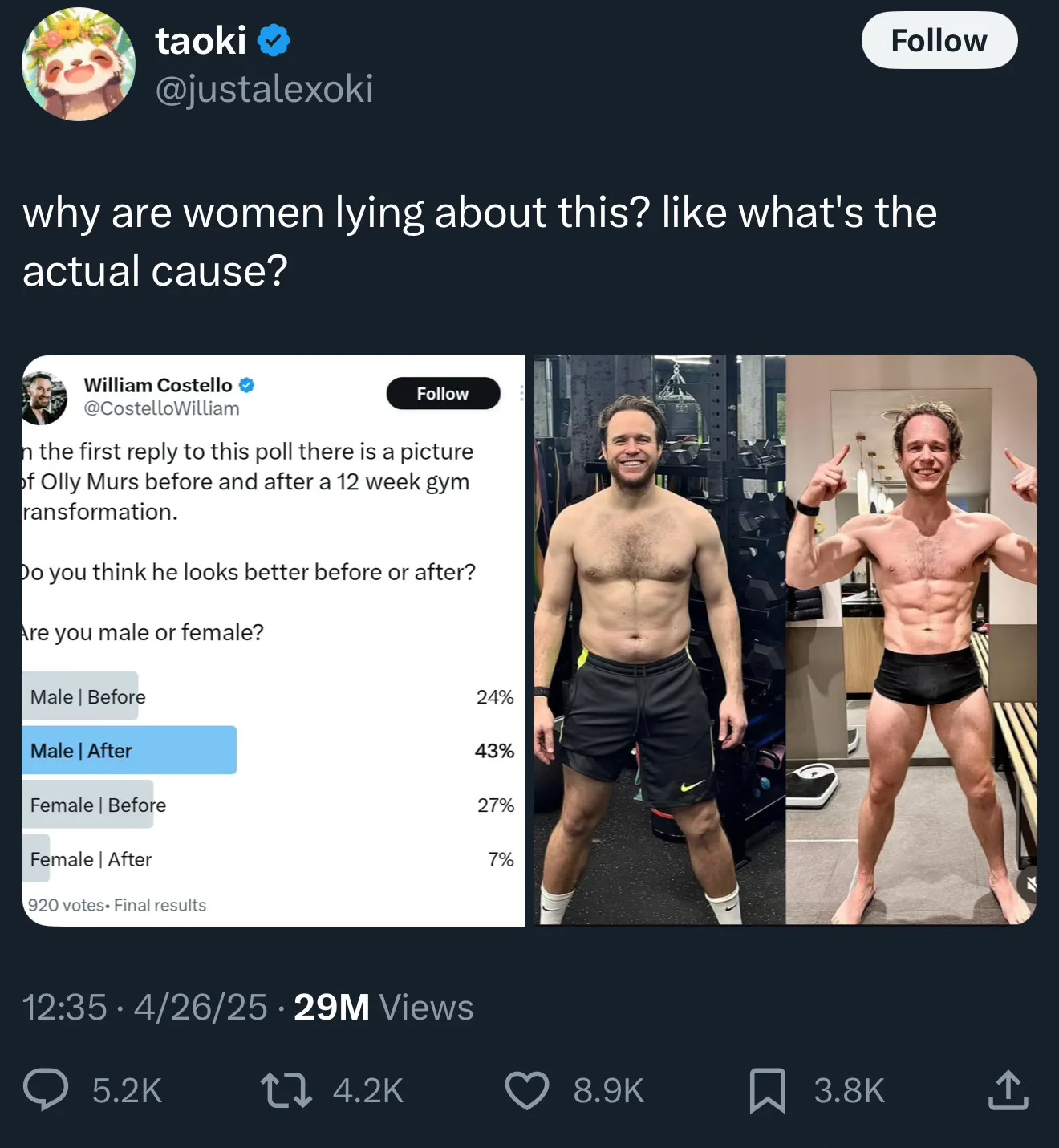

Anyway, Olly Murs has got ripped. He used to have a dad bod but now he is a gym rat. A researcher, William Costello, at the University of Texas posted before and after shots of Murs, interested in which people thought looked better. Oh and his Twitter poll allowed you to say if you were a man or a woman, when you made your choice between Olly Before and Olly After.

The results came in… and Twitter was not happy. Because while men thought ripped Olly looked best, women seemed to prefer dad-bod Olly by a large margin. Here is the outraged screenshot:

Liars! Liars! How dare they? Olly had done all the physical things that gamified bros think are the route to success - worked out, lost weight. And yet the women of Twitter gave him no credit. They must be misstating things.

Another place you see this is with the great AI Art debate. Ted Chiang’s piece in The New Yorker set off a great wave of very angry comments that prompt-engineering was real effort and should not be denigrated. Here’s a great example - the effort is now in the ‘idea’ of the AI art not in the production.

What’s kind of weird about this is that the justification for AI art is not about the output. It’s perfectly reasonable, I suppose, to say that if you like AI art, who cares how it was produced. But there is a new brand of argument that the ‘work’ put into coming up with the prompt to DALL-E should be commended. That all effort should be respected and lauded by everyone else, no matter how minimal it was.

The common theme in all of this is of course ‘respect’. That most desired and desirable commodity.

And herein lies the problem. You cannot directly purchase respect. You can of course purchase lots of things that might invoke respect from others - be it cars, clothes, housing, weird golden sprayed trophies. But the thing you really want, you cannot buy wholesale.

Respect is a by-product of other things. And what’s especially frustrating is there is no guarantee that those other things will provide you with respect even if they bequeath it to other people.

This will not shock anyone aware of Britain’s class system. The two cruellest words in the English language are actually French - nouveau riche. A time honoured theme of British shows about class - which is all British shows - is the character who has made a fortune but cannot buy the respect of those born into the upper class. Whether this makes the nouveau riche character a figure of fun (Hyacinth Bucket or Alan Partridge) or a lovable protagonist (Danny Dyer in the must-see Rivals) the key plot device is the unbreachable gap between the perceived means for acquiring respect and its actual attainment.

The political philosopher Jon Elster has a lovely section of his Explaining Social Behaviour (one of the great books of social science) where he talks about by-products.

A factor that complicates the wish-want distinction is that in some cases I can get X by doing A, but only if I do A in order to get Y. If I work hard to explain the neurophysiological basis of emotion and succeed, I may earn a high reputation. If I throw myself into work for a political cause, I may discover at the end of the process that I have also acquired a ‘‘character.’’ If I play the piano well, I may impress others. (p.86)

Elster’s distinction is interesting here. I pursue one goal directly and honestly (studying emotions) and it in turn has an indirect benefit (scholarly reputation). Sounds great! I’m a scholar - I’d love to have a good reputation! But wait…

These indirect benefits are parasitic on the main goal of the activity. If my motivation as a scholar is to earn a reputation, I’m less likely to earn one. (p.86)

Oh…

Elster’s paradox is that if I try and aim at the desired by-product directly I actually make it harder to achieve. Here is how he describes it.

Musical glory or social success falls in the category of states that are essentially by-products – states that cannot be realized by actions motivated only by the desire to realize them. These are states that may come about, but not be brought about intentionally by a simple decision. They include the desire to forget, the desire to believe, the desire to desire (such as the desire to overcome sexual impotence), the desire to sleep, the desire to laugh (one cannot tickle oneself ), and the desire to overcome stuttering. Attempts to realize these desires are likely to be ineffectual and can even make matters worse. (p.86)

This is one of my favourite pages in social science. It tells us something deep that I think we all suspected might be true but rather hoped wasn’t: there are some things in life over which we really have no direct control.

And worse, the more we want them, the less likely we are to get them. We cannot make someone love us, we cannot make bad thoughts go away, we cannot make ourselves aroused or sleepy. These are states of living that cannot be viewed as achievable targets that we simply and methodically work towards.

Real life cannot be gamified.

I’m not sure I blame people for believing otherwise. It feels in many ways as if it can be. We live in what Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy call an ‘ordinal society’ - a world in which the market, the government, and increasingly our peers, understand us as datapoints. We have credit scores, we have follower counts, we have employers that assign us KPIs. Social control is about assigning these numbers - creating a ‘meritocracy’ that relies on its participants believing that the numbers are meaningful both extrinsically and intrinsically.

So it is no surprise that gamification is such an attractive possibility for many people. It provides a clear set of rules and procedures for success and a single number - our individual EXP - that in turn opens access to goodies such as better jobs, better credit, and more online interactions.

But this ‘levelling up’ is a phantom. Nobody is forced to really take it seriously. Others are not condemned to love us or respect us because we have succeeded in the game of life. Indeed, per Elster, they might just hate us more. We, the winners, think of them as newbs and NPCs, because we cannot countenance that real humans don’t respect our fake achievements.

And it is this deeply human problem that haunts our broligarch friends. They cannot make others like them, respect them, laugh at their jokes. And the harder they try to achieve this - by buying social media sites, funding preferred political candidates, lambasting their workforces - the further away they get.

It’s a Geek Tragedy.

Worth staying for the punchline.

The Elster book is great. The phenomenon reminds me of undergraduates who ask what do I need to do to get a first class degree or early career colleagues who ask what do I need to do to get a Full Professorship by 40. The answer is never what they want to hear…