Some desk-clearing up front. I’m delighted to announce that I am now Prospect’s monthly columnist, taking over from Substack’s finest Sam Freedman (who is writing an excellent column for The Observer). My first column is just out and looks at whatever happened to the Rejoin campaign and its beautiful blue berets. And also, as I mentioned in my last post, Rethink is back for its second season with me as host. This week’s episode is on the Civil Service, where I am joined by an all-star cast: Gus O’Donnell, Jen Pahlka, Hannah White, Aaron Maniam, and Joe Hill. It will be up from tomorrow at 4pm on Radio 4 or here.

I’m not aware of that many social scientists who have played the muse for Oscar-winning film directors. Perhaps that day will yet come for me. But for Thomas Schelling this fantasy came true, as well as winning the Nobel Prize in Economics, and creating the entire field of game theory in international relations. So, perhaps not in fact for me.

The Oscar-winning director in question was Stanley Kubrick, who actually only won for cinematography for 2001 A Space Odyssey, losing out on Best Director four times. Should you think life is fair, I will simply note that this places him behind Mel Gibson on that particular list.

Anyway enough kvetching about Oscar injustices. The film in question that brought Thomas Schelling and Stanley Kubrick together was of course, Dr Strangelove, the cold-war satire featuring the eponymous mad scientist, played by Peter Sellers and modelled on some mix of the (err… controversial) rocket-scientist Wernher von Braun and the nuclear physicist Edward Teller.

Far from being the wacky professor, Schelling was actually an advisor to Kubrick about the game theory of nuclear warfare - aka Mutually Assured Destruction. Kubrick had bought the rights to the thriller Red Alert, which Schelling had reviewed for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. So as part of Kubrick’s adaptation he chatted with Schelling in 1960, the same year that Schelling published his classic The Strategy of Conflict.

That book was Schelling’s first lengthy treatment of the game theory of international conflict - and in particular it focused on bargaining in the Cold War. The key question for the two nuclear superpowers was how to deter one another from launching nuclear missiles. And this compelled both sides to signal resolve and credibility if threatened. One might simply do that through a ‘costly signal’ - spending more resources than you would if you didn’t really care how the conflict was resolved - hence the need for arms races.

But you might also do some really costly things to signal credibility. Anyone who has taken an intro to game theory will know about the idea of making a credible commitment by reducing your options. If you burn your bridges behind you, you have to stand and fight. What looks like a worse outcomes (fewer options, including retreat) actually makes you stronger because your opponent will intuit that you would only burn your bridges if you are really committed to the fight. And then hopefully your opponent will simply back down.

We can get more costly still. Sometimes we might not only want to make firm commitments, we might want to signal high levels of uncertainty. Our opponent is always trying to guess something unknown about us - how much do we really care about what we are bargaining over. We could do that definitively by tying our hands or making very costly choices. But we could also do that by behaving more randomly.

Schelling argued that sometimes making retaliation uncertain rather than certain, improves your bargaining position. Schelling pithily titled his chapter on this strategy “The Threat That Leaves Something to Chance”. Schelling notes that this shouldn’t really work - if you say you are going to retaliate if someone does something you don’t like and then you fail to retaliate, that seems a rather poor deterrent. As Schelling notes:

As a rule, one must threaten that he will act, not that he may act, if the threat fails. To say that one may act is to say that one may not, and to say this is to confess that one has kept the power of decision — that one is not committed. (p.187)

So, how can uncertainty actually help you in bargaining? Here is Schelling again:

The key to these threats is that, though one may or may not carry them out if the threatened party fails to comply, the final decision is not altogether under the threatener's control. The threat is not quite of the form “I may or may not, according as I choose,” but, has an element of, “I may or may not, and even I can't be altogether sure.” (p.188)

What Schelling is getting at here is the idea of ‘brinksmanship’ - escalating your retaliation and keeping open the option that things may get even worse. And that means opening up the possibility - but not certainty - that things might get really out of hand. Like nuclear war for example. Or let’s take a rather less apocalyptic outcome, again from Schelling.

“Rocking the boat” is a good example. If I say, “Row, or I'll tip the boat over and drown us both,” you'll say you don't believe me. But if I rock the boat so that it may tip over, you'll be more impressed. If I can't administer pain short of death for the two of us, a “little bit” of death, in the form of a small probability that the boat will tip over, is a near equivalent. But, to make it work, I must really put the boat in jeopardy; just saying that I may turn us both over is unconvincing. (p.196)

Well, that concerns me about getting in a boat with unreliable people ever again.

And this is where we approach Dr Strangelove. Bargaining through brinksmanship means creating uncertainty about whether you are going to do something really really crazy. This is why people often credit Schelling with the ‘madman’ theory of bargaining, though he doesn’t use this phrase himself.

You know who did? That delightful old devil, Richard Milhous Nixon. Nixon coined the ‘Madman Theory’ and his idea was that his bargaining position in Vietnam would be strengthened if he created massive amounts of uncertainty about whether he would do something crazy, like launch nuclear weapons at North Vietnam.

Oh and there’s someone else who likes this theory. Someone you were probably expecting would have made an appearance in this post by now. But I do love the long open.

That is of course Donald J Trump. Trump has regularly claimed to be using the madman theory - in his first term over the never-ending conflict in Korea, and during the 2024 Presidential campaign about Russia and China. Trump believes his unpredictability is what makes him so good at crafting and winning deals.

To which I say, what deals?

President Deals seems to have rather few so far. Trump was quite insistent that he would end the Ukraine War on day one, and after eventually noting that day one was just a bit of hyperbole, he seems further than ever away from a deal to end the war.

It seems the types of deals Trump was looking for were ones where the US would insert itself into the negotiations by demanding perennial control over Ukraine’s minerals and guaranteeing nothing in return. That was not a deal Ukraine felt that had to except. And nor has Vladimir Putin been swayed by Trump’s ‘madman’ strategy, whereby he occasionally sends all caps tweets out demanding that Putin STOP doing something or other, and then not doing anything in response.

When it comes to trade deals, this week the Trump administration was reduced to asking other countries to come with their last best offers for deals, ahead of the June resumption of Liberation Day. Strangely, America’s trading partners have not in fact been rushing to bend the knee and make Trump the kind of asymmetrical trade deal he clearly wants. Indeed, per the over-used Michael Corleone line, their offer to Trump is nothing.

Well… there is one country that has already cut a deal with the US. Trusty old Britain, whose special relationship appears to have garnered a promise to limit the flat tariff to ten percent (now also the deal that almost everyone else currently has) and to reduce the steel and aluminium tariffs from 25% to zero. Unfortunately, this does not actually appear to have been come into force and Trump decided to raise his universal steel and aluminium tariff for everyone to 50% but let Britain have its 25% discount. Which means the grand sum of Britain’s deal with Trump is that it has the same flat tariff as everyone else and the initial 25% steel and aluminium tariff that it was trying to bargain down.

And that’s what negotiating with Donald Trump gets you. Any special deal you think you might be getting to avoid the punishment beatings given elsewhere might just be removed. Look at Columbia University - it originally bent the knee and Trump appeared to turn his attention to destroying Harvard University, including by removing all its federal funding and trying to stop it from having any foreign students at all, both new and existing. That was very bad for Harvard and in the case of student visa was fortunately legally postponed.

But it hasn’t really worked out for Columbia to have cut a deal. They are still having almost all their federal grants withdrawn and the State Department has decided to delay issuing any student visas (or visiting scholar visas) to all US universities. So Columbia has ended up in basically the same situation as Harvard after making a deal.

In turn that has put universities off more generally from trying to cut a deal. Trump’s attempt to make an example of Harvard has indeed caused enormous grief for Harvard but it has not brought other universities to the table. Partly because of sympathy for Harvard (just imagine…) and partly because the case of Columbia demonstrates that deals will just be reneged upon.

Even Elon Musk has discovered that there is no way of guaranteeing that Trump won’t undercut any promise. Musk’s preferred candidate for head of NASA, Jared Isaacman, has been canned by the Trump administration (and will almost certainly be replaced by someone worse…). Musk is of course now in full warfare with Trump about his deficit-busting Big Beautiful Bill. Now, almost no-one in the world feels sorry for Musk, who has truly made his own bed (for the two hours a day he appears to sleep). But it goes to show that no-one can depend on a deal with Donald Trump.

And that’s because they are not deals. A deal is when you bargain over some political position or some economic price - blustering, escalating and playing brinksmanship as you go - and then you decide on a final contract.

The classic madman strategy may or may not be effective - political scientists tend to be skeptical - but it is what you do before you strike a deal. You act crazy like you will only accept some outrageous outcome and that you might blow it all up in a fit of pique if you don’t get what you want. But once you have struck the deal, it sticks.

By contrast, Donald Trump is playing the madman strategy after he cuts deals with people. An agreement with Trump is just a temporary prelude to further chaos. To go back to the old Schelling analysis, it’s as if John F Kennedy had waited until after Khrushchev had decided to back down and withdraw missiles from Cuba to go full on madman and threaten to nuke Moscow.

The classic madman strategy works like this: you convince your bargaining partner that you are willing to do crazy things while bargaining so that they give you a better deal in order to avoid the small probability of an apocalypse during the bargaining process. People are comparing the expected utility of a certain slightly-unfavourable outcome to playing a lottery with nuclear weapons, whose outcome could be really really unfavourable. They accordingly take the sure thing. So madness works.

It does not work if you cut a deal and then start behaving like a madman. Taking the deal is now not taking the sure thing. It is opting into the madness. Perhaps better to take the crappy sure thing outcome - higher tariffs - then entering into a deal where whatever advantages you get might be pulled out from underneath you any second and you are humiliated.

Or in the case of universities, better to suck up a few years of having federal funding cut than give into a deal where next week Steven Miller might ask to personally approve your syllabi or insist that College Republicans get given A’s or whatever other arbitrary stunt might get pulled.

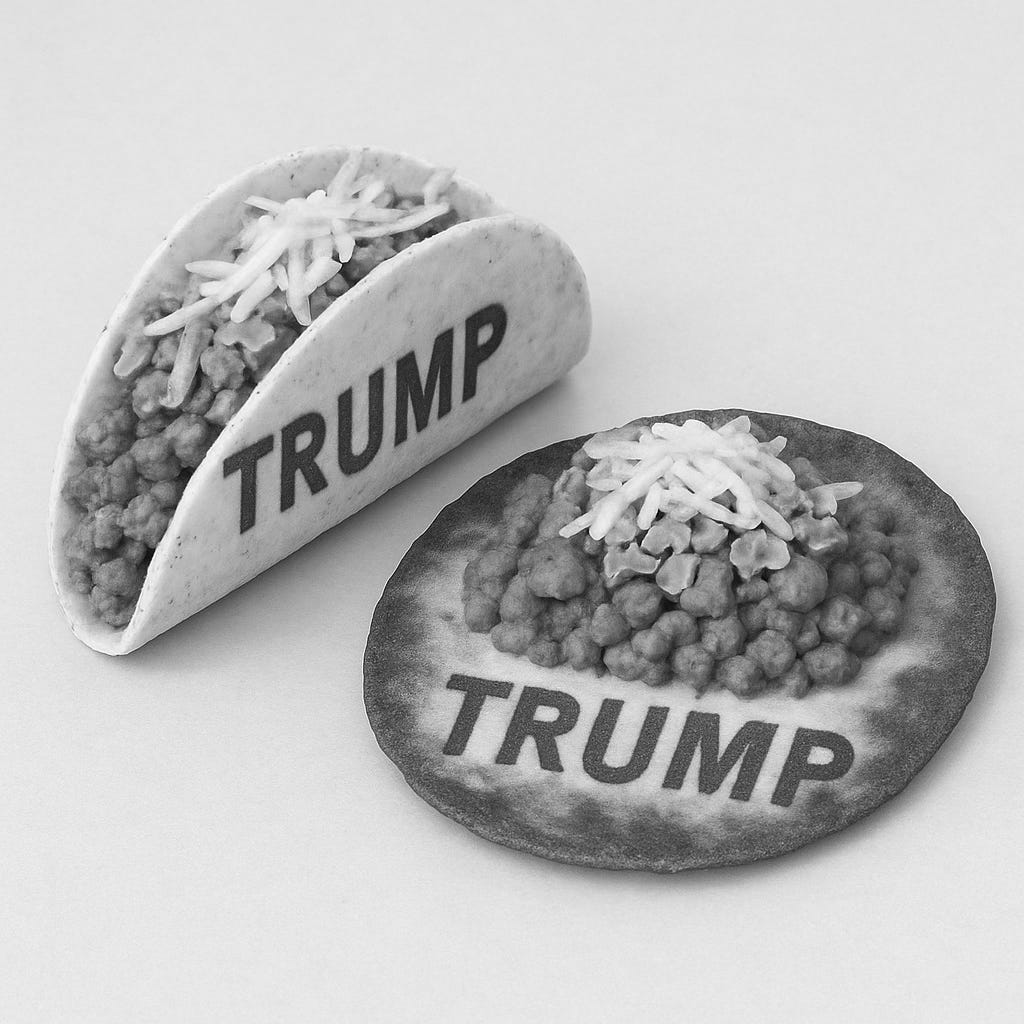

This is why I don’t think the TACO designation for Trump quite works, or at least that that’s the full story. For those who have somehow missed the last two weeks of online discourse, TACO stands for Trump Always Chickens Out, and was coined by the brilliantly acerbic FT markets columnist Robert Armstrong. The TACO trade relies on not taking Trump’s threats seriously and assuming he will always back down when push comes to shove.

So I agree that Trump does often back down after making a threat. But that is all part of the pre-deal world of escalation, and maybe even a part of what Trump believes is his madman strategy. It doesn’t really work now because people know that Trump’s plan is to pretend to be mad and make insane threats and then back off them. Trump keeps announcing that he is a ‘crazy guy’ and his bargaining partners now just pat him on the back and say ‘gosh, aren’t you just’ and then wait for the wind to change.

But TACO is only half the story. As I’ve argued, Trump is equally erratic after he signs deals. He is playing the madman before and playing the madman after. So you can’t rest easy once you have got through the TACO period. Let’s say you wait for Trump to ‘chicken out’ and then you cut a deal with him that isn’t so bad after all. Sounds great! Except, as Keir Starmer now knows, days after the deal is struck, Trump undermines it, tries it on, asks for impossible new changes, etc etc.

And that’s why I don’t think markets should be so sanguine. Yes, the initial threats and escalation are often BS. But let’s say Trump does finally sign some not so terrible looking trade deals over the next few months. What on earth makes anyone think he is going to stand by them?

The problem is not just TACO, it is TOSTADA.

Trump Often Signs Then Abandons Deals Anyway

And look we all love tostadas. But compared to tacos, they are messier and prone to getting burned. Much like accepting a deal with Donald Trump.

Well written and thought out .....

well put - and why i argue you can't analyse Trump using traditional policy wonk tools, you really need a psychiatrist