OK summer break over, alas… Have you missed me? Despite not writing any Substacks for a couple of months I have been busy. I have written a couple of pieces in my new role as Prospect’s UK politics columnist, including this month’s cover story on whether ‘left populism’ might work for Labour. And the new season of Rethink has just started with an episode on that highly consensual topic - the meaning of terrorism. Knock yourselves out.

But before I left you all, I did promise a little something…

I began this three part series of migration and the UK thinking, oh I’ll write something about my issues with Labour’s immigration white paper and a few suggestions about alternate policies and then I’ll be done.

Ho ho ho.

Instead, in my first post I felt compelled to write about the concerning trend towards ethnonationalist (or, in some less extreme cases, let’s call it ‘ethno-curious’) rhetoric in the UK. Sam Freedman followed up on that with a tough j’accuse piece, which I strongly recommend. But to those who perhaps misread my piece - or read the piece they wanted to read - it wasn’t really about immigration; it was about people defining white British as an ur-category of British ethnicity which implicitly downgraded other British citizens. I remain deeply skeptical of people doing this.

It is also a distinct debate from talking about the merits or demerits of recent high levels of immigration. Yes of course the parents of some of those non-white British citizens might indeed have been immigrants in the past. But I don’t understand why non-white British citizens today should apologise for immigration over the past few years. And I suspect that my detractors will struggle on that point too.

In any case I have apparently been labelled as ‘left-liberal’ for my temerity - something that might shock people who know my views on the merits of say wealth taxation, policing, or deregulation. But in our new ‘post-liberal’ era, all politics seems defined on one’s views about the merits of immigration and previous left-right categories have dissolved into thin air.

My second piece lost about half my audience by moving to data analysis. Don’t worry, won’t make that mistake today ;) But Political Calculus is a data-friendly zone and I think it’s important to try and unknot some of the varied strands of British public opinion about immigration, which I think have created a great deal of confusion.

To recap, these are that (a) attitudes to immigration are thermostatic and so the average Brit has become more opposed to immigration in the last few years of the ‘Boriswave’ of migrants; (b) that places in Britain with more immigrants are more positive towards immigration (including just among white British people in these places); and (c) that there is some evidence that people in places with unusually high increases in local immigration become less supportive of immigration.

TLDR - high levels of immigration are associated with positive attitudes towards immigrants; big changes (increases) in immigration produce more negative attitudes. Hence we can have the paradox of an ever more diverse Britain being both more overall supportive of migrants and more concerned about reducing migration.

OK Professor, what do we do with all this? Glad you asked.

In this third piece I want to build on the previous two pieces - the first normative, the second empirical - and suggest an immigration policy framework that can reconcile these contradictions. Oh, and I am doing so during a summer of political convulsions over hotels holding asylum seekers. Wish me luck. Actually, wish yourselves luck because this won’t be short…

Immigration is Politics

Immigration is an inherently political issue. I firmly disagree with the idea that immigration policy can be left entirely with a technocratic group who decide what level or type of immigration is best for the country and that the ‘hoi polloi’ should be ignored. I also am amply aware that immigration is recklessly manipulated by malign actors who seek to inflame the public and are quietly - indeed, apparently now not so quietly - quite content about violent riots outside hotels.

There is no consensual way through Britain’s immigration debate. First because there are legitimate disagreements. And second, because there are illegitimate disagreements.

So we need to think about tradeoffs. But not in a bloodless, ‘what’s best for GDP?’ manner. There are tradeoffs in people’s preferences. Some people really do value lower immigration in ways that don’t correspond to its economics benefits or costs. These people can vote. And it is elected politicians who resolve tradeoffs. So this cannot be reduced to an economic calculus.

But nor can we wish away the economic impacts of immigration. If you are an immigration-skeptic you might read the previous sentence and think, oh good he agrees with me that immigration takes jobs and lowers wages. And you would, I’m afraid, be wrong - I don’t agree with you.

Instead I agree with the broad consensus among economists (basically everyone except George Borjas) that immigration has a net positive impact on the economy. And that’s certainly what the OBR thinks too. You should feel welcome to disagree with me and I look forward to your lengthy, data-driven response paper…

In my view the basic tradeoff among existing British citizens is that many people think immigration is too high - whether this is motivated by cultural concerns, a sense that change is too fast, ethno-nationalism, concerns about housing affordability, reading the front page of newspapers, whatever - but the economic impact of immigration is broadly positive.

So, we can have lower numbers and make some voters happier but potentially poorer (in aggregate); or higher numbers and make some voters unhappier but potentially richer.

This gives us two groups of people so far who are core to the immigration tradeoff - people who are anti-immigration (typically a plurality of the country but it depends) and people who either have pro-immigration preferences, again for whatever reason, or who clearly benefit economically from immigration - many businesses and HMT at a minimum.

And there is a third group to consider - immigrants themselves.

The core of my argument is that we need an immigration policy that respects all three groups.

That means understanding that overall public opinion is thermostatic and that immigration has indeed been unprecedentedly high over the past few years and hence a majority of people think immigration needs to be cut. I think liberals are kidding themselves if they think these people are somehow misled or don’t know the real numbers etc. Immigration will need to be (likely substantially) lower than half a million net immigrants a year if public opinion is to be respected. This is the part that pro-immigration people don’t really want to hear.

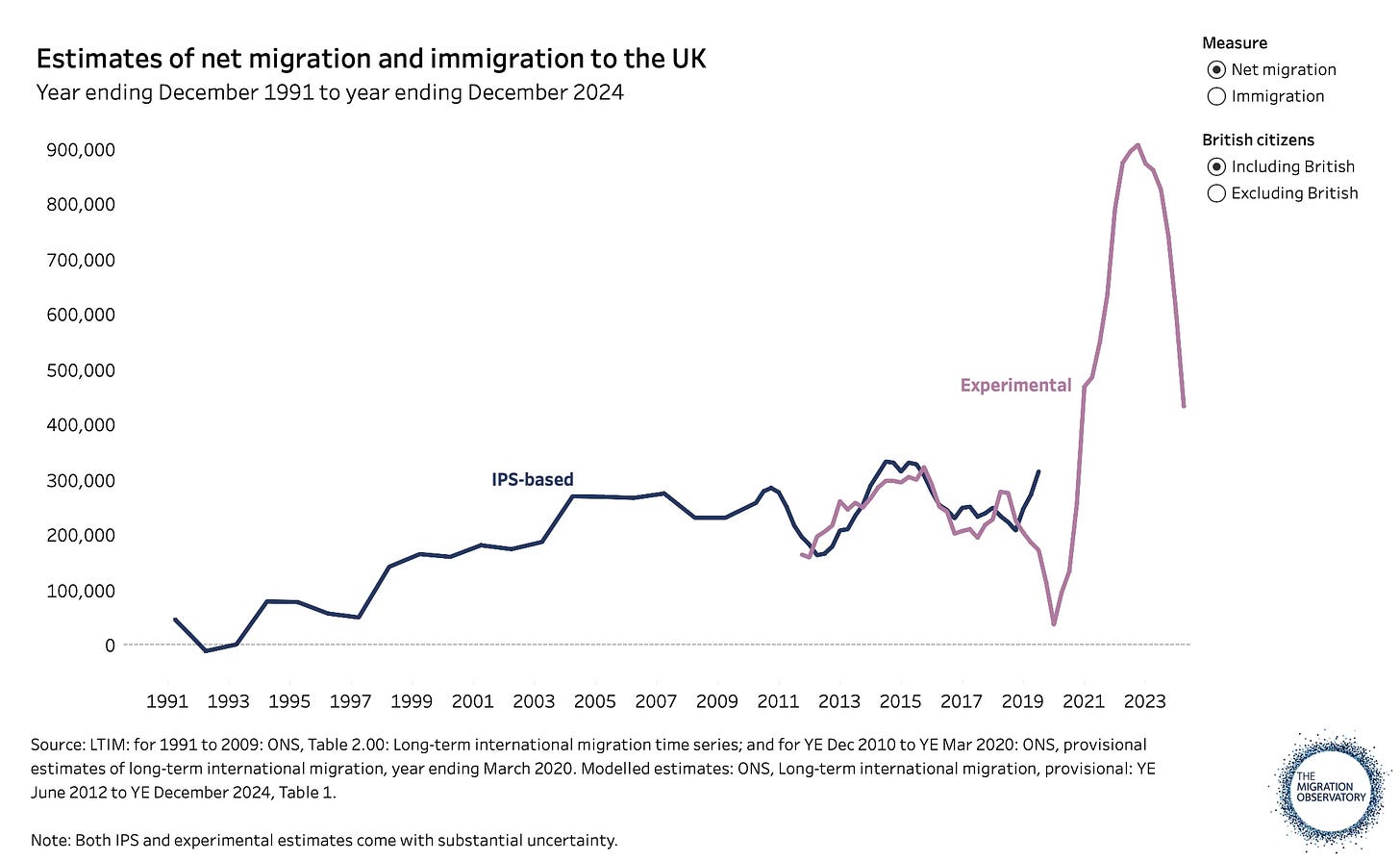

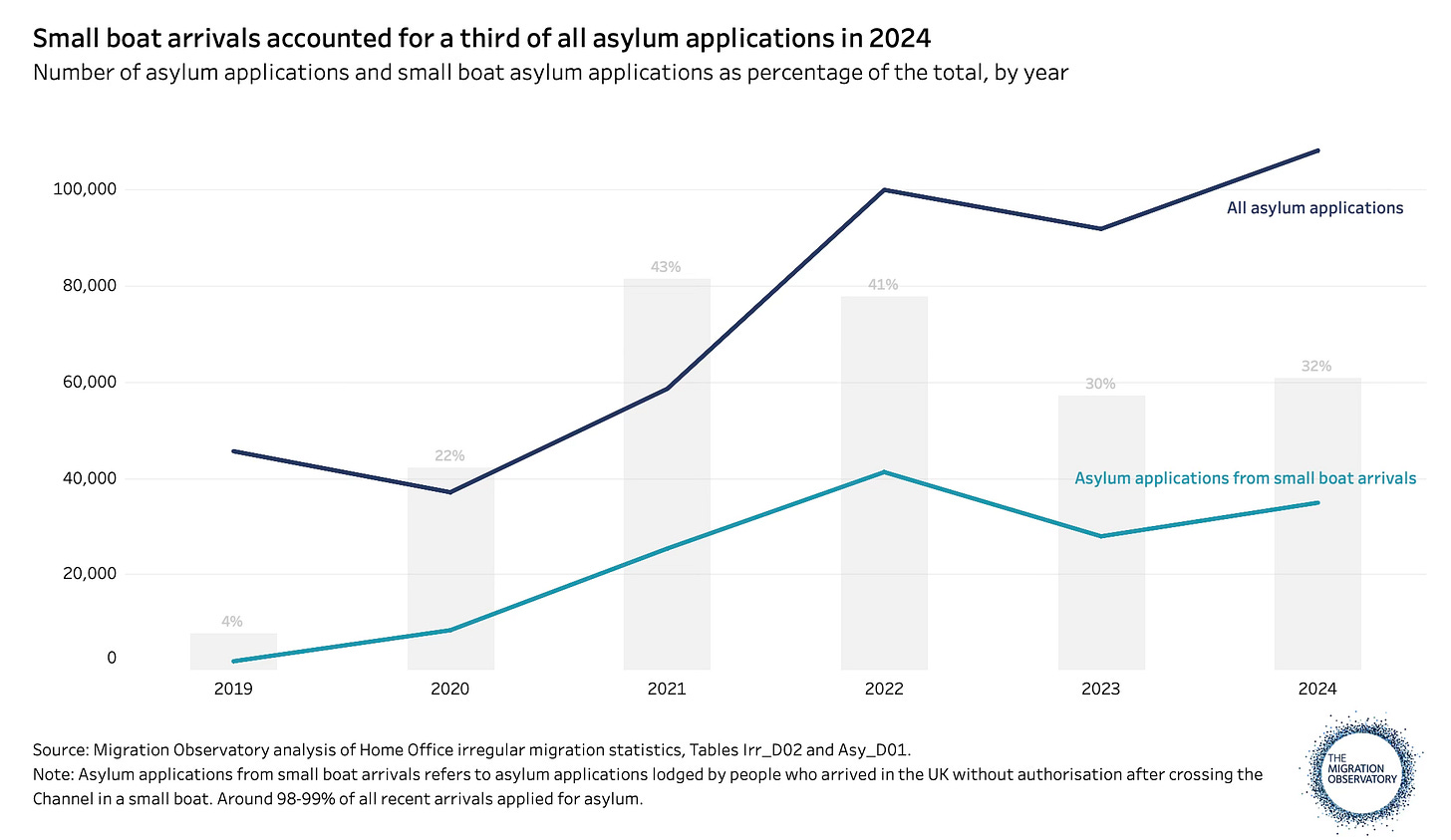

To wit, look at this figure from Oxford’s Migration Observatory and tell me that you are remotely surprised that (a) people who are immigration-skeptics are upset, or (b) that the average voter is now more concerned about immigration than they were a few years ago.

However, thinking through the politics of immigration also means understanding that cutting immigration can have serious economic costs and that while British people want lower immigration in general terms, when asked about specific groups (except asylum seekers) they tend to be OK with keeping numbers steady. The care sector, the university sector, the construction sector, the financial sector, the NHS - to a greater or lesser degree, they are all very reliant on access to immigrants. This is the part anti-immigration people don’t really want to hear.

Then finally we have the issue of treating those immigrants who currently live, or will live, in the UK with the respect we would want shown to us if we lived or worked abroad. That means rhetorically - no more talking about ‘islands of strangers’ or ‘incalculable damage’. And it means in policy terms - having clear, consistent, and affordable criteria for settlement and citizenship; not only emphasising but also aiding integration. And it means avoiding creating ‘two-tier’ legal systems, where different people permanently resident in the UK have fundamentally different legal rights.

In other words, this means treating everyone like an adult and behaving like an adult. Current immigration has been at likely unsustainable levels. It will have to come down and it almost certainly will. But we also cannot function as an economy without immigrants, not only because our birth rates are extremely low, but also because, even though it might not be fashionable to say so, the global economy remains highly integrated and Britain is a service-exporter, which means lots of people flying in and out of Heathrow and bringing in skills from abroad. Finally, it also means treating others who we have granted entry as we would wish to be treated.

How to Select

OK, that was all quite general and grandiloquent. What does it actually mean in terms of immigration policies? Who are we selecting and how well are we doing that? Let’s start with the easy stuff.

Skilled Worker Visas: in a post-Brexit world, the UK has been in the position to regulate quite stringently the types of people who can move to Britain to take on paid employment. Before Brexit anyone from the EU could come and take any kind of work. Indeed, arguably they could also come and not work, though Britain did retain the right to remove them in that case (which seems not to have been exercised to any great deal). Non-EU citizens always had to acquire a work visa and in recent times that has been a so called Tier 2 visa, now renamed the Skilled Worker visa.

A number of people thought that after Brexit we would move to an Australian-style visa system since that is what Boris Johnson regularly advocated. And there are indeed points as part of the new British system. But it’s not quite Australian since for the UK you have to have a job offer (except in one case I will come to), whereas it is possible to acquire enough points in Australia from education, experience, age etc to acquire the visa without a job offer.

For the UK you acquire points to get the skilled worker visa but 50 of these are mandatory and come from having a job offer (20), at an appropriate skill level (20), and being able to speak English (10). You then need twenty more points which come from being paid more than £25k, or having a PhD, or being in a shortage occupation. In reality, those last twenty are almost certainly going to happen by virtue of the fact that applicants must also be paid the ‘going rate’ for their profession, which is bottoms out at £33,400 and going to rise. That is true for every job except health and social work, or where you are already on a skilled worker visa, where £25,000 is about the lowest salary you can have.

The going rate can also be very high for particular skilled workers. Chief execs have to be paid more than £88,000. Social scientists £40,400. Electrical engineers £58,700. And so on. I am currently hiring for a centre manager position and the salary for that to meet the criteria for visa sponsorship would be £54,400. That latter figure is around the 85th percentile of the income distribution among taxpayers. Even the £33,400 number is above the 60th percentile among taxpayers.

So, excluding health and social care workers, it seems to me that the skilled worker visa program is working as advertised. It is not easy to get one. You already have to have a job offer and that job has to pay substantially more than the median British taxpayer earns. The job itself has to be skilled - i.e. require a certain level of education. And the salary figures are closely calibrated to labor market reality by profession.

Of course, if immigration remained ‘too high’ you could push up the salary requirements but at a certain point that would probably stop functioning well except for finance. But there is flexibility there too, to tighten or loosen as needed. The Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) do a pretty good job in my view on this. My sense in talking to members of the MAC is they are very cognisant of the need to balance bringing in needed skilled labour with the overall stress of high numbers, and they are quite happy to raise thresholds if they feel they need to. All in all, IMO, if you oppose this system as too lenient, you basically oppose any viable skilled worker immigration.

There is one ‘points-based’ visa that is more Australian in nature and that’s the Global Talent Visa, which does not require a job offer. If you have won a ‘globally prestigious prize’ that will do it for you - but this list of prizes is so hilariously rarefied that is applies to a couple of thousand Oscar and Nobel Prize winners. So the actual way it works is getting sponsored by one of Britain’s learned societies, usually if you have been offered an academic job. That means suckers like me, as a Fellow of the British Academy, get the exciting and unpaid role of judging the merits of visa applicants to the UK. Thanks Home Office! Your invoice is in the mail.

The Global Talent Visa is for my taste a little bit mysterious for applicants and indeed for assessors and I do rather wonder if it might make sense just to provide a certain number of these visas to major research universities / science institutions and say if they have a professor or senior researcher job and they find someone they want to employ in it, that constitutes ‘global talent’. I realise that this makes it more employer-based and less ‘points like’ though, so there are trade-offs. Perhaps we just need a new skilled worker visa for academics / scientists.

Anyway I like the Global Talent Visa and so my thanks go to Dominic Cummings, though I understand he is not always my biggest fan. Thanks anyway Dom!

So a couple of quick recommendations:

Keep skilled visa salary thresholds flexible but tied to MAC recommendations

Provide clearer guidance on Global Talent Visa application or replace with an academics/science specific skilled worker visa

In sum, I think the current system broadly respects those worried about numbers (skilled worker visas are among most popular visa types even for anti-immigration people and the numbers aren’t huge), those worried about businesses and making Britain attractive to skilled immigrants, and skilled migrants themselves, though I think the immigration fees are too high. To wit…

Skilled Worker Dependents: I didn’t mention a couple of important things - fees and dependents. Skilled workers can bring spouses and children. I should note that the visa and perhaps more importantly, NHS fees, for doing so are enormously costly. Here is a worked example.

Imagine you are hiring a physics professor from abroad and she has a husband and three children. And let’s imagine we are not using the Global Talent Visa but a standard Skilled Worker one and the university hiring them refuses to pay any of these fees (in reality universities will often cover the visa application and likely the NHS fees, they may or may not cover those for dependents).

Let’s start with the visa fee for the physicist - £1,519 assuming they are outside the UK currently (madly, it’s even more expensive applying from within the UK). Then there is the NHS surcharge, which must be paid up front for five years. That is £1,035 a year, or £5,175. So that’s an upfront cost of £6,694.

But wait… what about the spouse and three children? Well they also have to pay the £1,519 each and the £5,175 each. So, bit of math… we have 5 x £6,694 = £33,740.

That is… a lot in fees up front. Indeed it is roughly the amount in gross terms that a skilled worker has to earn annually to be employed in the UK. And sad to say, our tax rate is not zero percent.

Now it is certainly true that for many, perhaps most, skilled workers, employers will bite the bullet and cover these fees. It’s a cost of doing business. But in my view it’s basically daylight robbery by the Home Office. And it is far, far more than other countries charge.

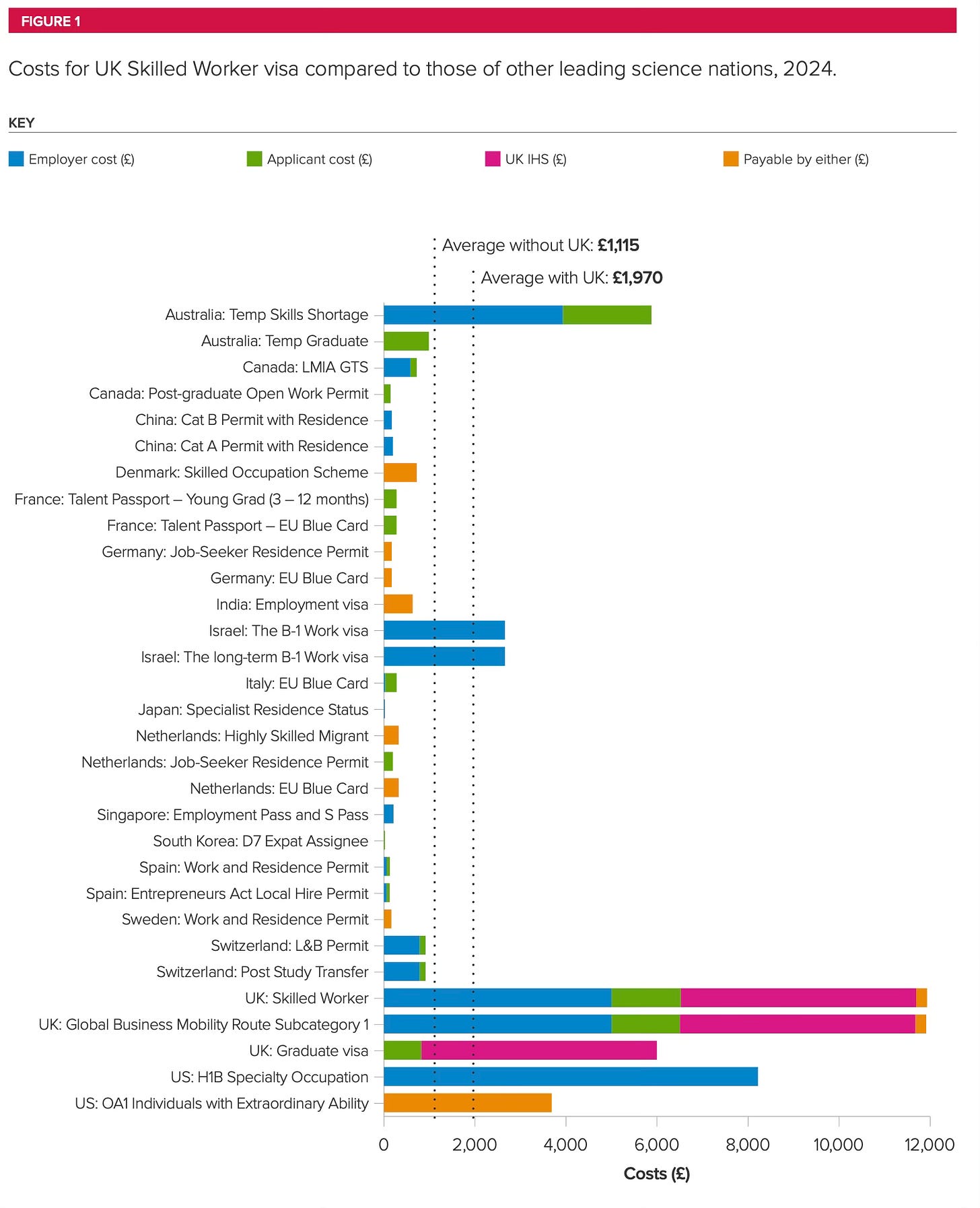

Here is a figure on the costs of skilled worker visas (not even including dependents) in the UK as compared to other countries, from the Royal Society.

Other than the US H1B, nothing comes remotely close. And look how much of our relative disadvantage comes from those NHS fees…

So if skilled worker visas are already hard to acquire because of high salary and skills requirements and the visa application costs are so extortionate, how the hell has Britain had a surge in skilled worker visas such that there has been much cavilling and moaning about legal immigration, at least on the right of the political spectrum?

Ah… there is one thing I brushed over above - the lower salaries for health and social care workers. Now I don’t think foreign doctors are being exploited here but for less well paid hospital workers and particularly social care workers, those salaries really are quite low.

And what’s more - those NHS immigration charges that apply to both visa-holders and dependents? Not true for health and social care workers.

Where our unlucky physicist above had to earn a high salary and somehow have £33,740 to spend on up-front visa fees, a social care worker can make £25,000 and have no such fees, for them or their family (save the visa application fees if not covered).

This helps to explain the surge in numbers of immigrants on skilled worker and dependent visas over the past couple of years and why James Cleverly as Home Secretary reversed course on permitting dependents for health and social care workers, and why in turn Labour has not altered that direction of travel.

On the respect front, this is all a bit of a bind.

In terms of people concerned about rising immigration, this has very clearly been a contributor to the surge in net arrivals and popular discontent with numbers.

In terms of demand for immigrants, this is happening because of the crushing bind the NHS and social care sectors are in financially, not least because of the (IMO foolish) abandonment by Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng of the health and social care levy introduced by Boris Johnson, Rishi Sunak and Sajid Javid. And the equally unfortunate failure of Labour to reintroduce it. Accordingly the demand for relatively low-paid labour from abroad to fill roles continues unabated.

Finally, there is the issue of respect for migrants themselves - social care workers are now forced to leave their families behind if they want to work in the UK - not an experience many of us would wish to have.

I’ll be blunt - the solution here is likely for all of us to have to pay more for health and social care. Whether that is through higher taxes or supplementary NHS contributions; through a Dilnot review of care or through even higher private social care costs; it’s hard to know. But if immigration numbers are to be lowered that’s the tradeoff that has to happen. And that does look like the direction of travel.

So what do I think in terms of recommendations here:

Lower fees along with (maybe) numbers: Our fees are just astronomical compared to other countries and it makes it harder to attract the most skilled immigrants that command the highest public support. If you are worried that lower fees mean higher numbers of new immigrants then adjust the salary threshold or other conditions.

Remove the NHS surcharge from children: Children are relatively low cost to the NHS (at least post their entry into the world and first few months) but pay the same fee as adults. For families coming for skilled jobs, the upfront cost of paying the NHS fees is enormous and it is very unclear this reflects anything like the cost for a child for year of using NHS (certainly beyond the (high) taxes already paid by the skilled worker visa holder).

Re-implement a hypothecated health and social care tax and cut health and social care visa numbers: If we want to avoid large numbers of relatively low-paid care workers on visas (and I am not entirely sure we do but if you want to reduce numbers this is an obvious place) then we will likely need to find and train UK-based care workers instead. Since care work is hard and often unattractive and pay is poor, there is an argument for higher pay in the sector but that has to come from somewhere. Bring back the levy.

Students

The other place where we have seen a recent tightening of immigration policy is with students. Well not exactly students but rather their dependents. It is now not possible to bring dependents with you unless you are doing a research Masters or PhD. The other piece of tightening applies to ex-students - the graduate visa which allows you to work in the UK post graduation at salary rates substantially below a skilled worker visa has been cut from 24 months to 18 months.

Students were a contributor to the surge in net migration numbers over the past few years and there are three reasons for that. First, the post-COVID boom in new arrivals, making up for the lack during the pandemic. Second, the ever-tightening financial circumstances for the university sector, which has meant foreign students have become ever more important to staying afloat. And third, the expansion of a lot of low tariff universities of dubious repute, bringing in foreign students as proverbial ‘visa mills’. Perhaps that is a little unfair but there is quite wide variation in prestige among those universities with the highest number of foreign students as you can see here. The three largest recipients for example are UCL, BPP University, and the University of Hertfordshire.

I might lose my liberal bona fides here but I think this last group has made it very hard for the rest of the sector. A similar thing, by the way, has happened in Canada and the government there has cracked down hard. The problem we face in the UK is that the Home Office treats the whole sector the same. I am not suggesting we go full Nick Timothy and only permit top Russell Group universities to bring in foreign students. People might think that would be in my own university’s interest but the sector is interconnected - for example, my pension at Oxford relies on the health of the sector as a whole. Imagine that, solidarity from dons at high table.

I do think though that some line will need to be drawn however that can keep foreign students coming to established universities in both research intensive universities and in regional universities that act as economic hubs for their locality, such as Sunderland or Lincoln, while preventing university offshoots and low-ranking business schools in London from overwhelming the student visa system.

Rather than make life hard for all students - which appears to have been the model of this and previous governments - I would advise the government to look at different student visa models for different types of institution, along the Canadian model.

Going back to point number two - the financial stress on universities - this raises questions about the merit of the government’s idea to have universities pay a levy on foreign students. If the sector is relying on foreign students to keep afloat because tuition fees did not rise with inflation for a decade and because government funding has gone down, what pray tell do you think might happen if you directly tax universities for the foreign students they are bringing on to make up this gap?

Unless the government is planning some, as yet unannounced, increase in funding per domestic student, this will simply hasten the day several universities collapse and the government has to deal with lots of ‘my son’s course at Durham was shut’ articles in the Daily Mail.

Finally, we have the ‘graduate visa’ which allows graduates to stay up to eighteen months before they transition on to a skilled worker or other visa. This was for two years but was reduced recently. I have mixed views about this. Obviously it’s good for my sector. But its presence does incentivise the bad actors in HE (i.e. the ‘degree mill’ programs) to advertise it as part of their package to students. My sector should be encouraging people to come to the UK to study, not specifically as a on-ramp to working here. They should be staying to work because we value their UK education, not getting their UK education simply as a means to work here.

So what we could do instead is go back to the two-year graduate visa for graduates of certain British universities and push it back down to one year for others. That differentiation would be basically the same as the one I outline above - pushing universities whose gig is basically to attract foreign students as a pass through to working here into a lower category. Sorry lads, but you’re ruining it for the rest of us.

And so, that leaves us with three recommendations:

Consider differentiating within the sector, Canada style to reduce overall numbers

Abandon the foreign students levy, unless you plan on compensating universities

Differentiate the graduate worker visa so that students from some universities get two years and others one, along the lines of differentiation above.

Family

One of the places where Britain’s immigration policy is substantially more restrictive than almost any other wealthy country is in terms of bringing non-UK spouses to the UK. It’s also a nightmare to apply for for Brits returning from abroad to the UK with non-UK family since the time frames for getting the visa are vague and lengthy. Several British-national colleagues at Oxford returning from academic jobs in the States - presumably the kind of people we still want to attract back to the UK, or have we fully gone down the rabbit-hole? - have horror stories about having to be separated from their spouses for several months while they await a visa.

But it’s not just bureaucratic slowness or arbitrariness that makes Britain’s spousal and dependent visa regime draconian - it’s the threshold on how much you have to make to live with your family. The threshold is £29,000, which is basically median income (as paid by taxpayers). What that means is that fully half of British taxpayers are banned by the state from bringing their spouse to the UK. Half.

Oh and that’s ignoring people outside the workforce. Imagine you are a stay at home parent with British citizenship. Well your income is zero, and since you cannot use your foreign spouse’s income in its stead, you are miles away from being able be able to live with your family in the UK unless your spouse can qualify for another visa, most likely a skilled worker visa (oh and they also have to have a job offer from a UK employer).

So it’s almost certainly substantially more than half of people. This is a far more draconian limit than most other countries.

Now, it is true I am sure that having such a high threshold reduces net immigration numbers. But we are not talking about people bringing in their ‘aunties’ or ‘cousin Joe’. This is their life partner. And I don’t know about you, but one of the things that I would hope that as a British citizen I have a right to is to live with the person I love.

This is ultimately a moral claim. Others may wish to say, too bad, earn more. I disagree. And, since it’s a moral claim - I think I’m right and you’re wrong ;)

So what do I think we should do?

Reduce the spousal salary threshold back down to £18,000 again.

Or frankly, get rid of it

Settlement

It used to be that our debates about immigration were simply about net migration numbers and our ‘lack of control’. Since Brexit ended that lack of control but people are still angry, you will not be surprised that a new scapegoat has been found and that is people who have already come to Britain on whatever set of rules we happened to have at that date.

Britain does not have good recent history in remembering what immigration and citizenship policy it had in the past and how that might apply to the rights of people who entered at that point. I remind you of the Windrush scheme, where people who entered Britain entirely legally in the 1950s and 1960s were, decades on, deprived of their right to remain, largely because the Home Office had forgotten about them and got rid of all their documents. A decade on from the scandal, the Home Office is still applying all the sympathy and good judgment that it is usually associated with…

For those people who might not be familiar with settlement, it’s often referred to as Indefinite Leave to Remain, since it provides just that. Other normal countries would call it permanent residency. It is not quite the same as being a citizen. You can lose it if you leave the UK for two years without returning or if you go to jail for offences with a sentence longer than a year. It does not provide voting rights. And it certainly doesn’t stop Robert Jenrick from endlessly differentiating you from British citizens.

But it does allow access to public welfare benefits that people on visas before ILR are banned from accessing. It is an unfortunate fact of British public life that large proportions of the population appear to think immigrants can immediately ‘get on welfare’ and really nothing could be further from the truth. But once you have ILR the British social system treats you the same as everyone else and you no longer have to pay visa fees or NHS fees.

By the way, there are quite a lot of people who stay indefinitely on ILR because they are not permitted dual citizenship by their country of origin - most prominently India. So, if you were wondering, that explains why not everyone takes up citizenship.

You can acquire ILR after five years (three if you have a global talent visa) and after taking the Life in the UK test, meeting quite high salary thresholds, not leaving the country for more than six months in a year, and paying an exorbitant fee of over £3000 (far higher than any other country). After a year of ILR you can apply for citizenship (unless you were already married to a Brit in which case you can do it immediately).

Getting ILR is already hard and expensive, compared to anywhere else. So of course, the British government has talked about making it harder and more expensive. They have spoken about extending the wait time, and presumably the egregious NHS fees, to TEN years, albeit with some mealy-mouthed humming and erring about maybe it will be less time for people who have made a ‘contribution’.

Why? Because of the so-called Boriswave of large numbers of new legal immigrants in the past couple of years, particularly from Hong Kong and on the health and social care visa. There are ‘concerns’ that these people might stay. To which I say, did the government plan on telling people it encouraged to flee Hong Kong that they would suddenly need to pay up or go back?

There is talk not only about applying the ten year principle to new arrivals but to people already here who have not yet acquired ILR. The government, in its great wisdom, decided to hint at this, and also that the ten years might be reduced to five for some undecided group of people, and oh don’t worry we’ll give you an answer later this year. Maybe.

Permit me to be blunt. I cannot think of anything less British than changing the rules under which people made huge life decisions. Oh wait, I can. Floating with the press that you might or might not make those changes, leaving hundreds of thousands of people who have come here legally in a state of limbo.

Already there are people (Chris Philp… grrr…) telling Shabana Mahmood that the Home Office should renege on the terms under which people arrived in Britain over the past few years and make them wait another five years for ILR. This will mean thousands of pounds in unexpected costs for possibly millions of people and the likelihood of various Windrushesque stories of families separated from children, nurses and care workers bankrupted, universities losing whole departments worth of staff.

Oh, and every single arrival on the Hong Kong scheme, people who thought that they were fleeing arbitrary government decision making. And all so the government could pull the rug out from people who understandably might have thought the British government meant what it said.

You can change rules applying to new arrivals if you want. I suggest the government think carefully about how to do that because I can tell you from my sector that we won’t be able to attract any world-class scientists and scholars if we force them to pay another £30,000 in fees on top of the egregious existing amount. But at least people would know what they were getting into. Changing the rules after the fact is scummy behaviour and it won’t end well, mark my words.

If the government is worried about ILR being too lenient, well (a) they shouldn’t be, because it isn’t as compared to almost anywhere else; and (b) they could if they had to extend it by a year or two, rather than another five.

I cannot imagine how hard it will be to attract new skilled workers to Britain - in health, AI, science, all the things the government says it wants - by saying, oh don’t worry, firstly you could make more elsewhere and secondly, you will have to wait twice as long here to stop paying visa fees. Sounds enticing…

On the respect front. I can understand that those people who want lower migration want it to also have happened in the past. But it didn’t. It is unBritish in my view to change rules on people. If needed, you can change future rules (though I disagree on length of extension). For those worried about attracting skilled migrants, increasing time to ILR would be a disaster. But most of all, in terms of respecting people already here, changing the rules would be a disgrace.

All I can say to the government on this is GET A GRIP. But if you want my advice it follows, in all caps, you know for emphasis:

DO NOT EXTEND ILR WAITING TIME TO TEN YEARS.

DEFINITELY DO NOT CHANGE THE RULES ON PEOPLE WHO ARE ALREADY HERE, YOU TOTAL LUNATICS

If you absolutely have to do something, extend the waiting time by a year to new ILR arrivals. But IMO don’t even do that. In fact, lower the egregious ILR fee to something more like £2,000

Asylum

Let the fun begin… Let me begin by acknowledging that I though think I have quite a bit of knowledge about most of the immigration system, this is absolutely my weak point. It is also where talking about legal versus illegal migration breaks down. Are asylum seekers crossing the channel in boats legal? Well, in international law, yes. Under current UK law… it’s complicated.

The 2023 Illegal Migration Act removed the right to claim asylum for people who arrived in the UK in ‘irregular’ fashion. Most parts of that Act have now been replaced by Labour’s own Border Security, Asylum and Immigration Bill which has shifted from what we might term a demand side approach (e.g. the Conservatives’ ill-starred Rwanda scheme, which was intended to reduce the demand to cross the channel on small boats by sending people who crossed to Rwanda for processing) to a supply-side approach, which pours money into ‘smashing the gangs’.

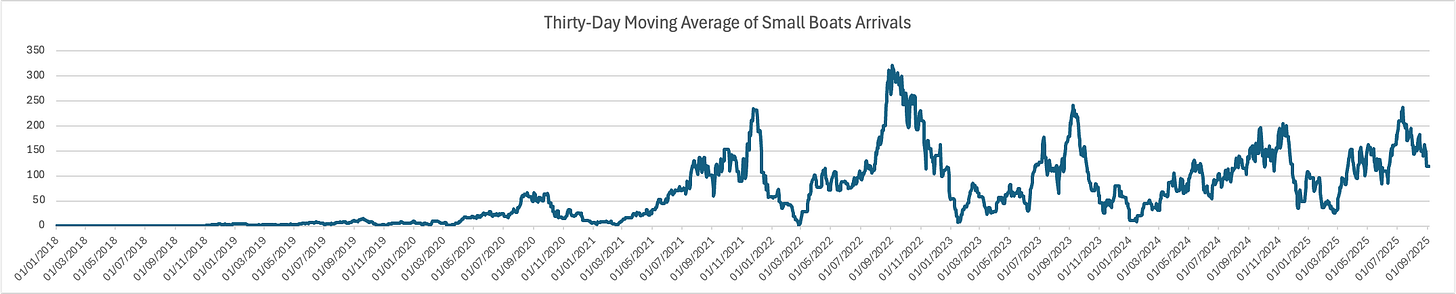

Bluntly, it doesn’t look like either approach has really worked. Here is a graph showing the thirty-day average of migrants arriving by small boats back to 2018. Look at my Excel graphing powers and tremble…

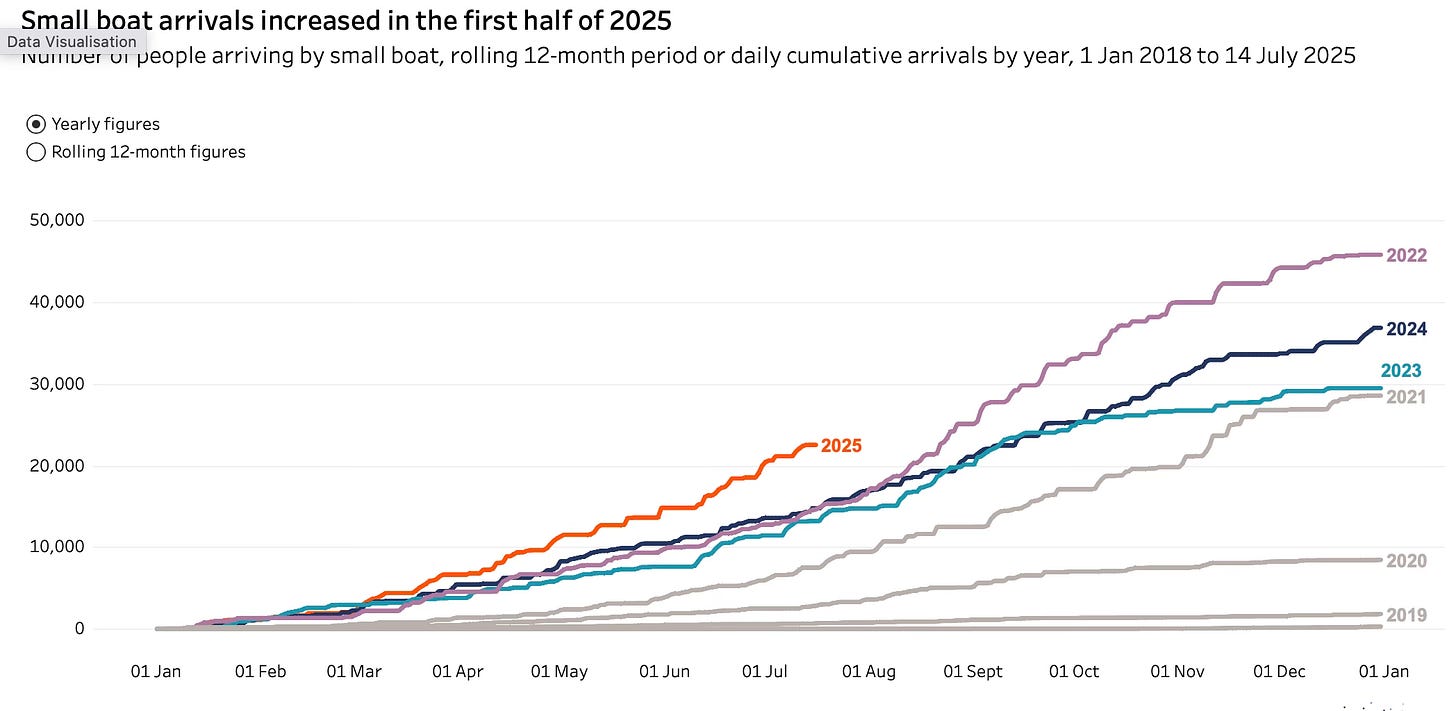

Well you can see Rishi Sunak’s problem. He arrived at the end of 2022, during the peak period of small boat crossings and the following year they were still elevated. And has anything much changed with Keir Starmer in power? Not really, save the curve looks a bit higher during spring of 2025 than it had in previous years, presumably because of the very warm spring in Britain this year. That means comparing the trajectory over the course of the year, 2025 does look abnormal, as you can see in the graph below from the Oxford Migration Observatory. The question is how things go later in the year and whether the annual numbers really rise on 2024.

You will also note the first few years of these graph show very few migrants arriving in this fashion. This is a post COVID issue for the most part. Before that, people tended to arrive to claim asylum in the UK in different ways - oftentimes through illegal passage on lorries or aircraft, or by arriving on regular but time-limited visas and claiming asylum.

Indeed, although small boat arrivals are the most noticeable and salient way asylum seekers arrive (and about 95% of small boat arrivals claim asylum), it is actually a minority of all annual asylum claims even today. This useful figure from the Oxford Migration Observatory shows that they constitute just one one third of the over 100,000 asylum applications.

Both small boat crossings AND asylum applications really have been much higher in the 2022-2025 period than in recent memory. Put it this way, if David Cameron had got his wish of ‘tens of thousands’ of net migrants annually, that would have been met and exceeded by last year’s asylum applications alone.

I think we do need to be serious in noting that this does present a major political challenge to any government. It can’t be easily waved away. And it’s not crystal clear to me that moving to ‘safe and legal’ routes for asylum-seekers would either reduce numbers or public concern, though it would certainly save lives and might be worth pursuing on that basis.

Nor can we simply blame Brexit. The Dublin Agreement which asks member-states who were the first port of arrival for asylum seekers to take them back if they move to another member-state was rarely used by the UK - only around 500 times a year. That said, like the Rwanda scheme (at least in the eyes of its proponents) it may have a deterrent effect that is harder to measure.

I do not have any easy solutions to offer on small boats crossings. There are no bold bits of advice below… Maybe the one-in-one-out deal with France, or more patrols on the French coast, or replacing asylum hotels with ‘dorms’, or any other reform might help. I don’t know and I won’t pretend I do. Mahmood has a hard job ahead of her. The only advice I can give is for people to acknowledge that this is a serious issue, where there has been a dramatic increase in numbers in recent years and where public opinion has clearly shifted. So it would be very foolhardy to somehow wish this went away. It won’t.

What we can do, though, is be not only firm but fair. Britain may end up having ever more draconian rules about accessing asylum, particularly across the Channel. But that doesn’t excuse threatening violence against those who do cross (or asking people who do to be main guests at your conference…). How the tightly the law should be set on speech acts is contentious and I tend to have more American 1st Amendment style views than many of my readers. So legal consequences are challenging. But social norms and political speech? Absolutely we should denounce violence. I do hope we can have some agreement on that, particularly given recent outbreaks of political violence in America and elsewhere.

Select and Respect

OK, how did we do?

First, let’s start with people with people concerned about numbers. I agree with them that almost one million net arrivals in the UK per annum is not remotely sustainable, certainly politically, probably socially. If I had to pluck a number out of the air for what I do think is sustainable, if fairly generous, it would be around 300,000 people a year. Yes, that is much higher than David Cameron’s tens of thousands. But I will remind you he never got close to that. It is just slightly higher than the level of the mid 2000s, so adjusting for population increase, a similar annual percentage change. I won’t claim everyone will be happy with a number as high as 300,000 but if it is mostly made up of people the UK ‘selected’, through skilled worker visas, spouses, and students, I think that is viable.

It would also meet group two’s needs - people in the UK who want / need migrants. Because the secret is (not really a secret at all), with a rapidly increasing dependency ratio, the UK will need to increase the number of working age people in the country. If the choice is actually between retiring two or three years later or having this level of immigration, I suspect the British public will pick the latter, even if they moan as they do.

What’s more, if Britain’s comparative advantage is trade in international services, it will almost certainly need to remain open, in order to attract talent in areas from education to science, AI to finance, entertainment to sport, and so on.

Finally, we have migrants themselves. You will note above that one of my main concerns is treating people who are already here decently and as we would wish to be treated. That means not nickel and diming them on incessant fees. It also means not changing the rules. We really are behaving quite badly in international terms on both those fronts and that is the fault of the Home Office always looking to change fees or rules every time it faces a bad headline.

Do I think all this would make Britain happy about immigration? Not really. But that’s because we are decades into politicians and the press talking about it as a public bad. I don’t expect that to change easily but I do think it’s important it become less salient and that is only going to happen with (a) a reduction in numbers, (b) a sense that Britain does indeed select who comes in, and (c) somehow managing to resolve the small boats issue, whose salience ends up poisoning the politics of normal migration.

There is good news ahead for Labour. Immediate good news in that the small boat numbers will decline ‘naturally’ as we enter the autumn and winter. And medium-run good news in that the Boriswave won’t continue because (a) the Ukraine and Hong Kong schemes happened in the past, (b) various restrictions imposed by James Cleverly as Home Secretary have indeed reduced care worker and student dependents. Oh and (c) the recent climate around immigration in UK politics might just make us less attractive - though likely to exactly the types of people that we still do want to attract. Them’s the breaks.

So things might cool down somewhat. But I suspect probably not, because the Conservatives are in a life or death struggle with Reform and so will go into an out-competing mode on immigration. Labour need to find away to assuage public concerns about the recently very high numbers that were, after all, the direct consequence of the policies imposed by the previous government, without falling into the temptation of constantly demeaning immigrants who are already here.

This surely should not be beyond the wit of man or indeed the PM. A narrative that acknowledges that numbers have been too high, that the UK nonetheless needs a moderate amount of immigration for economic and family reunification reasons, and that immigrants to Britain contribute across sectors from health to education, finance to science, sport to culture. I know the government struggle with narratives but come on, it’s not that hard. Something for immigration-skeptics, something for immigration-supporters, and something for immigrants.

Remember, respect goes three ways.

I really like your broad framing on 'select and respect'. It feels a useful lens through which to have this discussion, though it won't surprise you that I'd put some of the specific parameters in different places! And it was great to read an academic willing to break cover on the fact that universities are not all the same and should not be treated as such.

Three thoughts I had:

1. Although the average working immigrant may be economically beneficial, a substantial minority are not. Reducing the numbers of these is a win-win and does not involve the trade-off you describe.

2. The one element I felt the piece missed was the crucial element of unfairness that many believe underpin the current regime. I happen to agree with you that we make it too hard for UK citizens to bring their spouses over. But until this month, refugees could bring over their families with no such maintenance requirements - and then be jumped to the front of the social housing queue (see Alice Thomson's very good piece in the Times this week). How can that disparate treatment be fair?

3. I would add a third element, after 'select and respect', which is 'deport'. The inability to automatically deport those who do wrong - whether that is committing a serious crime, or simply breaching the terms of a short-stay visa - hamstrings our ability functioning immigration system. Indeed, a functioning deportation system would mean we could be less harsh at denying tourist visas to young, unattached people from developing countries: the 'flight risk' issue would disappear if we could be confident we could deport those who breached their visa terms without being thwarted by human rights appeals.

Finally, I think our biggest underlying difference is that - as I read it - you see ILR, and citizenship, as rights that should accrue, and it is wrong for us to withhold them. As someone who lived for two and a half years in a foreign country, I always felt strongly that I was a guest in their home, with a duty to respect their culture and ways, and that anything I were to receive from them would have been a privilege at their discretion, not a right.

"I think liberals are kidding themselves if they think these people are somehow misled or don’t know the real numbers etc."

That people don't know the real numbers is just a solidly documented fact. But it is a completely different question whether anything could be done about this; and again a different question whether it would make any difference anyway.

Immigration concerns are widely viewed as having swung the Brexit referendum. But look at where the net migration curve was in 2016: at roughly the level which you estimate would be a sustainable level now (after a further decade of declining living standards).