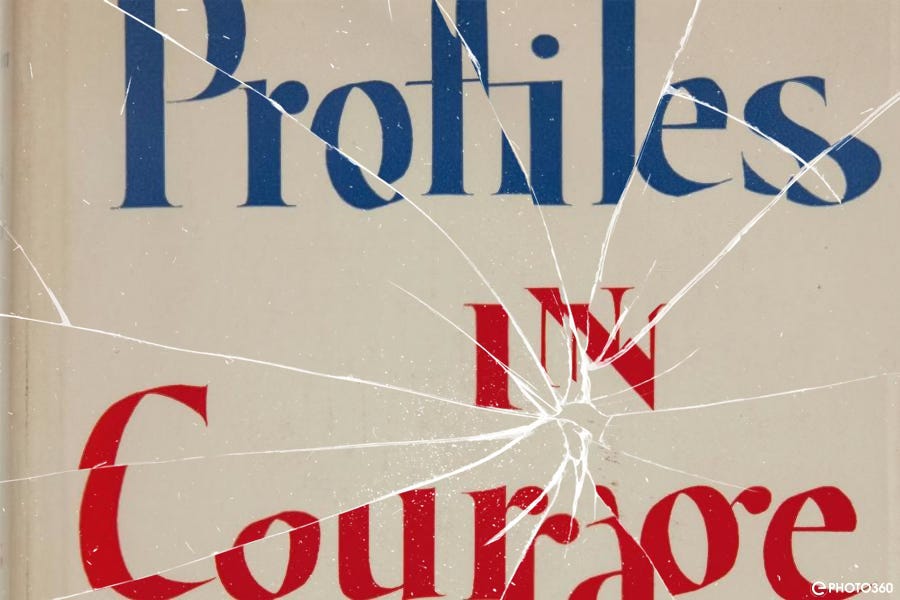

Profiles in Discourage

Labour's punting of social care reflects a bigger problem of indecision

To govern is to choose.

But what if it’s not?

What if you win an enormous parliamentary majority and then you do very little with it? No-one can really displace you for the remainder of your term. You have another four or so years to vacillate and procrastinate. And then maybe things will get better of their own accord and you can be re-elected at the end of it. After which you can enjoy another term of inaction.

Us political scientists tend to be rather realistic - you might say cynical - about the motives and behaviour of politicians. When we think about how they design their manifestos, our baseline is to assume that politicians are ‘office-oriented’ - that is, they are trying to maximise their chances of election and re-election for the sake simply of being in office. We sometimes use the idea of ‘psychic rents’ - there are consumption benefits of just being in power, regardless of what you do. Note, we aren’t saying politicians are corrupt - these rents are psychic not material. We’re just supposing that politicians are in it for the love of the game.

Now that’s a sometimes useful operating assumption for predicting how politicians might behave and why the ‘median voter theorem’, where politicians govern on behalf of the preferences of swing voters, tends to hold. But first, it’s probably not accurate since policies are much more volatile than that. So we often assume that politicians have ‘ideological’ motivations too, that ideological voters may have to be kept on side during elections, and hence swing voters don’t just get what they want and politicians are interested in more than just existing in office, they want to do something.

And second, it’s all a bit depressing. I’m very much in the Schumpeter camp of thinking democracy is ultimately just about competitive struggle for the people’s vote to acquire the right to rule. But while Schumpeterian democracy is still democratic if you do nothing while in office, that’s pretty nihilistic. The world changes, new challenges arrive, crises happen. And if you just fold your hands and tut like a priest at the funeral of an ill-behaved miscreant rather than, I don’t know, doing something, don’t be surprised when the Schumpeterian mechanism of ‘kicking the bums out’, decides you were the bums.

Long allusion. What I’m too obliquely referring to is the fundamental weakness of the new Labour government. They have come into office with a near unprecedented majority. And they are paralysed into inaction by… well I’m not entirely sure what.

But that paralysing venom has soaked into one of Britain’s most thorny social dilemmas, what to do about social care - that is, care for those who cannot easily look after themselves, in some cases working-age adults, but most commonly, older citizens who are suffering from dementia.

Social care reform has, to be fair to Labour, been in limbo for a decade and a half. (Can you paralyse a statue?). The basic problem is well-known. An aging population and the decline in cardio-vascular disease means an ever-greater number of people living much longer than earlier generations and suffering from Alzheimers and other chronic degenerative disorders. A little excursion into the history of Britain’s care sector might be helpful…

A History of Inaction

Britain’s social care sector sector emerged along with the NHS in 1948, with social security funding used to fund the relatively few individuals who needed care, albeit very much at the discretion of local authorities. In 1980, the Conservative government introduced a right for individuals with low incomes and very low assets to apply for social security support to live in private care-homes. As my colleague/spouse Jane Gingrich writes in her brilliant Making Markets in the Welfare State, this initially created what she calls a ‘pork barrel market’ in elderly care - private care homes with minimal regulation shot up to cater for this new subsidised group. Disused hotels along the British coast suddenly became care homes.

The rise in numbers eligible for this subsidy and the massive rise in private fees as providers took advantage meant that a decade later in 1990, a funding crunch came, and in response, local authorities were given financial responsibility for paying care homes and hence an incentive to keep costs low. This is when costs really started to shift onto individuals needing care. The sector became increasingly private and entirely structured around the incomes of those needing care. As Jane puts it “Wealthy users could buy high-quality care at high prices from exclusive private providers, low-income users received public funding for low-quality care, while middle-income users were stuck paying high fees while receiving the same low-quality care as the publicly-funded users” (p.184).

Labour’s response on entering office in 1997 was to try and improve standards by increasing spending on adult social care by about fifty percent and to increase somewhat the assets that recipients could keep. But they didn’t follow the Royal Commission’s advice to provide free personal care (though the Scottish Parliament did, meaning that care is very different across the nations of the UK).

When the coalition government in 2010 came into power they asked Sir Andrew Dilnot (disclosure: the long-time warden, recently retired, of my Oxford college) to chair a commission on the future of care. A year later, in 2011, the Dilnot Commission reported and recommended that the state ask individuals (above a certain income threshold) to pay the first £35,000 of care costs and thereafter the government would pay. In other words, England would have a social insurance style system for social care. You can hear Andrew explain how the policy works on an episode of BBC Rethink I hosted late last year. Parliament passed a Care Act in response in 2014. Great news, right?

Well… the cap on costs people would have to pay was delayed. It was to come in - with agreement from all the parties in the 2015 General Election - in 2016. But that was then delayed to 2020. You all remember 2020, so it didn't come in then either.

In the middle of this period, Theresa May decided, for reasons best known to her and her strategist Nick Timothy, to change the cap into a floor. Instead of limiting the amount anyone could spend, they advocated instead that costs be essentially unlimited but that £100,000 of assets could not be touched. This was substantially less generous than Dilnot’s plan. And it was political hemlock. It was immediately referred to as a ‘dementia tax’. May famously dropped the policy while claiming ‘nothing has changed’ and in part the policy and its embarrassing reversal were blamed for May’s electoral disaster as she lost her majority.

It was the May-Timothy gambit that appears to have been the core paralysing venom for social care in Britain. Because social care policy was blamed for electoral defeat it has been viewed as a political third rail that no-one should touch. This looked bad for the Dilnot plan and yet, miraculously, of all people, Boris Johnson looked like he might accomplish it. In 2021, Johnson, his Chancellor Rishi Sunak, and Health Secretary Sajid David, came up with a deal whereby national insurance taxes would be raised by 1.25%, raising £12billion per annum, and paying for both Dilnot (with a new cap of £86,000) and post-COVID healthcare costs. Hurrah for Boris!

Except, PM Boris was not much longer for this world. Conservatives, in part disgruntled by the NI increase, but mostly by Boris being Boris, ultimately dethroned the platinum king and had a new leader - a certain Liz Truss. Truss and her Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng were very unhappy with… basically any tax at all… but especially the rise that Johnson and Sunak had enacted. So in the most doomed Budget of all time, Kwarteng nixed it.

Very few elements of the Truss-Kwarteng budget still exist. Like a crap Ozymandias, ‘round the decay of that colossal wreck… the lone and level sands stretch far away’. Except for the nixing of the social care levy. That stayed. So Dilnot was put on ice, presumably until a Labour government came to power…

And that takes us to today. Rachel Reeves came in as Chancellor in July 2024 and immediately restored the social care levy, breathing new life into a battered care sector and setting to rights a historical injustice. Ha ha ha ha. No.

Instead, despite the earlier claims of now Health Secretary Wes Streeting, Reeves announced she was abandoning the reforms entirely. No reprieve was given in the Budget in October. Indeed, the direction of travel was probably obvious once the Winter Fuel Allowance going to pensioners was nixed. The spending was Not. Going. To. Happen.

And then the turn of 2025 and suddenly Labour were interested in social care again. Perhaps Dilnot might be resuscitated after all.

Psych.

Of course not. Instead, Streeting has announced YET ANOTHER COMMISSION, this time to be led by Louise Casey, holder of the Guinness World Record in leading government reviews. This review would report in 2028 and seek cross-party consensus just in time for the next election.

You will forgive me for my cynicism but that is not going to work. The chances of Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage playing nice with the Labour Party are essentially nil. Labour might just about be able to get Ed Davey not to be too mean. Also - and this is important - every government since 2010 has agreed on the principles of the Dilnot Review. There already is consensus on that. And an existing Care Act. And a previous mechanism of funding it that Labour didn’t introduce because they decided to rule out any personal tax raises (a decision that IMO will stand alongside David Cameron’s commitment to holding an EU Referendum in the legion of reluctant and mistaken election promises).

By the OBR’s calculations the Dilnot plan would cost between 0.2 and 0.25% of GDP per annum by the end of the century. That’s about £5-6 billion or 14 Brexit buses worth of spending. The social care levy would have brought in £12 billion (it was of course also going to pay for lots of healthcare catchup too). This is both a lot of money and almost rounding error for overall government spending. And you would think that a party traditionally less scared of taxes and spending would be willing to countenance it.

Standing Athwart Majority Government Screaming Stop

This reflects a broader problem with Labour. It’s not like I expected the Dilnot review to be implemented after July’s decision, so in a sense the Streeting announcement is better than nothing. But not much.

If you are fortunate enough to win an electoral majority numbering in the hundreds you really do need to DO SOMETHING WITH IT. Labour have a relatively long list of processes that have begun engaging in. But in terms of actual tangible accomplishments, it’s basically just on-shore wind farms and a few other policies from Ed Miliband and the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero. Yes, the conservative press hate Miliband’s policies but he is actually doing the things he said he would do, even though unpopular, because - and I can’t reiterate this enough - LABOUR HAVE A HUGE MAJORITY. Our electoral system has all kinds of problems but one thing it can do, by creating majorities, is enable effective government. So have an effect!

The American polling analyst Lakshya Jain had an interesting Twitter thread (here on BlueSky) about his frustration with the Democrats (who he supports). I don’t agree with all of it. But his point about the obsession with process over outcomes is crucial. The Democrats have spent too much time, he argues, on advertising and designing their big bills - IRA, GND, high-speed rail, rural broadband - and not enough on getting quick results from them. We have spoken a lot about the perceived failure of ‘deliverism’ in that Biden/ Harris were punished for the economy despite what seem quite rosy economic statistics by late 2024. But part of the problem was that the results of policies such as the Green New Deal hadn’t really hit the ground yet. What voters remembered was the inflation from 2022 (partly created by increased spending commitments) and the promises of the policies had not really manifested.

I think the critique is a little over done. Some policies had manifested and people still didn’t really care! But Jain is absolutely right that voters judge politicians on outcomes not processes, on results not promises. And, although processes are essential to produce outcomes, you need to get the process moving quickly and smoothly if you want the positive outcomes to help you by election time.

But on Lords Reform, on planning reform, now on social care - on all these policies that were apparently important to Labour - we are still in the foothills of process. Yes it would be nice if the process were consensual and we could all get along as we discuss alternatives but fairly soon we will find we have been talking and negotiating for five years and the election is here already. Right now, the Labour mantra seems to be ‘don’t just do something, stand there’.

Action for the sake of it is not Starmer’s way. Dare I say, it is a rather more Johnsonian urge. Johnson did get things done. I think we can all agree, not always to the betterment of the country. But the opposite strategy also has very clear limits. Tarik Abou Chadi and Tom O’Grady have an incisive article about what happens if you just try to muddle through. You become Olaf Scholz’s doomed coalition.

Yes it’s true the press will oppose you doing things - they will be unfair, biased, mean. But you already know that. And they won’t be nice to you just because you didn’t do anything either. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. So don’t don’t.

To return to the title of the post - political courage is not always rewarded. That is why it is courageous! But a lack of courage is liable to leave you in a worse place. Because it discourages your supporters, it discourages investors (who can’t be sure you will do what you said), and it discourages your own backbenchers.

To govern is to choose. So, choose something.

Courage mes amis.

My take is there was never a strategy for what to do in government. For a Party so obsessed with winning, it's startling that so little thought has been given to governing.

As any leader who's taken on a poison chalice knows, once you take over the reins, despite your best intentions, you end up consumed by immediate problems with little time to come up with a strategy to solve them.

The time for analysis was before the election. They should have come into government ready to enact a list of easy wins - like immediately setting up the Covid fraud investigation, action on water companies etc. But when you've not filled core vacancies and made a poor choice for Chief of Staff (twice) this is what happens.

I was a Campaign Manager for the local and general elections this year, and to say this is disappointing is an understatement.

This is so true. It's astonishing when one compares it to 2010 or 1997.

One other thing is the fact that our whole system - from civil servants to politicians to the people who lead reviews - seem to have just accepted that reviews or inquiries should take years. Why? What does this gain us? Especially on subjects where so much has been written by so many actors. The entire culture is too accepting of this.

If the Government did want to have a review on social care - perhaps to summarise what has changed since Dilnot - then very well, but why not say it must take no more than six months? One problem is there is no incentive on officials to show pace here - but ultimately the buck stops with Ministers (in both parties) who have been too accepting of such time scales.