Populism against Liberalism

The idea of a new woke elite against the masses is in vogue. But it's also vague.

This week I am turning, with some reluctance, to the debate in the UK about whether there is a new elite - a ‘new woke elite’ to be more precise - that governs the country. There has been much merriment on Twitter back and forth about this idea. As ever, I think it’s best to try and tease out the merits of such a claim with data. But I also want to highlight a theme from Why Politics Fails - elites are always counterposed to the ‘people’ - but it’s not clear that there is any consistent ‘will of the people’ out there.

And on Why Politics Fails, I’m delighted it was selected as an ‘unmissable’ politics book in Waterstones’ monthly newsletter. So, don’t miss it! You can order from Waterstones here. Or a signed copy from Topping here. Or at the behemoth here.

I swore I wasn’t going to get sucked in. I swore. But the debate about elites in British political life. well… more precisely ‘a new woke elite’, rumbles on. So let me begin by noting two things.

First off, if anyone qualifies as a member of a liberal elite it is surely an Oxford politics professor, living in the bubble of North Oxford, with degrees from multiple countries. No point in claiming otherwise I guess.

Second, I published a fairly successful academic book with ‘elite’ in the title (on the right of the figure above) - so I absolutely believe ‘elites’ are useful social science constructs. It’s totally legitimate to discuss elites.

But here’s the thing - social scientists have been discussing ‘new elites’ for the past century. And so every decade’s new elite is a later decade’s old elite.

At the end of the nineteenth century, we had Thorsten Veblen’s ‘Rise of the Leisure Class’, describing (and yes bemoaning) a new elite who displayed their status through orgies of conspicuous consumption. Vilfredo Pareto argued that elites continually circulate - there are always new elites, generally though not always the ‘most qualified’ people. Robert Michels (in the middle of the figure above) developed the ‘iron law of oligarchy’ - every democratic system or organisation must devolve into oligarchy controlled by a ‘leadership class’ of, you guessed it, elites.

And in the postwar era, C. Wright Mills famously wrote ‘The Power Elite’ (left in the image above), highlighting a new elite headed by those in charge of major corporations, the military, and government (which doesn’t sound enormously ‘woke’). The political scientist E. E. Schattschneider, critiquing ‘pluralist’ accounts that viewed American democracy as simply competing interest groups, declared “the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with an upper-class accent.”

And elites have been back in vogue in social science over the past few decades too. With David Samuels, I wrote Inequality and Democratisation: An Elite-Competition Approach. We argued that when democracy emerges it is typically because a new economic elite emerges that lacks political representation - think of the industrial and commercial classes in nineteenth century Britain - and is being expropriated by the existing old elite - think aristocratic landlords. For David and I, political change is not usually driven by mass movements but by disgruntled and disempowered elites. So trust me, I’m the last person to say we shouldn’t talk about elites.

I don’t think talking about elites is the problem. I think the problem is pretending that there is a coherent ‘people’ they can be counterposed to.

The New Populism

Absolutely core to the intellectual and political manifestations of ‘populism’ is the idea that the ‘people’ are not being listened to. That someone else is calling the shots. An unrepresentative elite. Whether that elite is in the political system itself, or as with the ‘new woke elite’, largely outside of the political system but somehow responsible for policies and politics, varies across populist arguments. But in common there is an elision of differences among the people and an exaggeration of differences between the people and whichever precise elite is being castigated.

It’s worth beginning by comparing the composition of Britain’s political elite over time to the composition of the people. In a chapter for the Institute for Fiscal Studies Deaton Review, Jane Gingrich and I looked at the educational and occupational backgrounds of MPs versus the population.

The first thing to note is that in educational terms, they have become more similar. It’s true that the vast majority of MPs have university backgrounds - but since the 1970s that has been true for well over sixty percent of them anyway. And the British public, with the mass expansion of higher education, now looks more like the political elite in educational terms. And on the flip side, the proportion of MPs with private education or Oxbridge degrees has declined considerably over the same period, to look much more like the population. So, look, you could write about how a new educated political elite has separated from the people but in my view that’s pretty hard to take from these figures.

Where I think there is more critique to be made of Parliament is in its occupational backgrounds. Never especially high to begin with, the proportion of MPs who worked in manual professions has collapsed since 1980, much more so than in the population at large. I think this is meaningful and scholars from Geoff Evans and James Tilley to Nick Carnes have written lucidly about the risks of this trend for representation.

Where are we Divided? Where are we United?

But let’s be honest. The attack on a ‘new woke elite’ is not really about Parliament. At least, it certainly doesn’t seem to be aimed at the political elite who have governed the UK since 2016. Instead the focus has been on “left-leaning elite graduates who live in the cities and the leafy commuter belt, who have hoovered up most of the gains from an economy built around them, who dominate the institutions, who impose their values on others, and who exclude the voice of millions.” To quote a recent article in The Sun.

So this seems to be people outside politics. I think. It’s a mix of demographics - education, residence, income (assuming that’s the hoovering of gains); political leanings (left); power (dominate the institutions - presumably not political ones); and actions (imposing their values on others and excluding the voice of millions).

Now let me be an annoying social scientist for a minute and say that it would be hard to construct a reliable index that includes things that are inputs into being an elite (education) and things that are stuff the elite does (exclude the voice of millions). Just as a measure of democracy ought not, in my view, include both formal processes (e.g. separation of powers) and then outcomes we expect democracy to have (e.g. economic growth, equality, happiness, etc).

And it does make it a little hard to assess because so many aspects are tautological - if we want to judge whether a new elite is especially powerful at getting what it wants but our definition of said elite is that it gets what it wants… well that’s not enormously helpful. And this, by the way, was the critique made of C. Wright Mills’ ‘power elite’. Everything old is new again.

So what I want to do is switch direction slightly and say, what does this imply about the people, against whose views the elite are apparently set? Presumably, the elite are socially liberal and the people are socially conservative - certainly that is the spirit off the argument about a ‘new woke elite’ - it’s about values rather than money.

One thing we could do to assess this then is to take a nice-big survey of the British population, which I just so happen to have to hand, in which they are asked a series of questions that tap both social and economic attitudes. Presumably, we would expect the people to have coherent social attitudes, which the new elite are attacking, dismissing, or undermining.

I’m going to use my YouGov survey of 3600 people from October 2022, which I’ve analysed in previous Substacks, and look at fifteen separate items I have. Some of these questions are the classic ones used for generations to analyse social authoritarianism / liberalism: support for the death penalty; agreement that “young people today don't have enough respect for traditional British values”; dis-agreement with “It is more important for children to have independence than respect for their elders.”

Then we have whether there is “one law for the rich and one for the poor”, that “working people get their fair share”, and “the people not politicians should make our most important decisions”.

I’ve then added a host of economic questions - about whether differences in income, wealth, or house prices are too large; whether the government should redistribute income, or wealth; and whether houses should be built locally.

Finally, I have some efficacy questions - is politics too complicated to understand, do officials care about ‘people like me’, and do ‘people like me’ have no say. Phew…

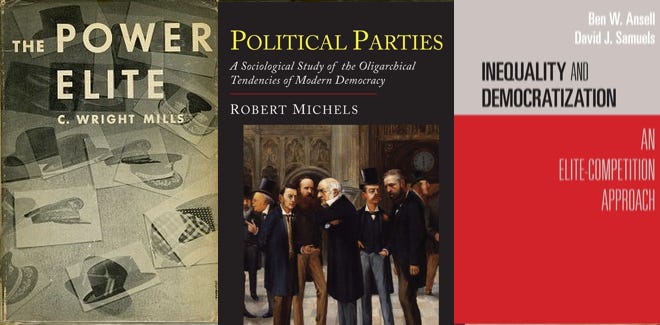

I’m going to use most of these questions in a moment to construct simpler indices of social attitudes. But before I do it’s worth looking at the variation in answers given to each. If the people had coherent views on the social issues that the new woke elite was disregarding, we’d expect least variation in the sample on these. But that ain’t what we see.

The table below shows the ‘coefficient of variation’ for each item - that’s the standard deviation in the sample normalised by the mean answer - this makes it comparable across items with slightly different scales. Bigger numbers mean more variation. And the table is ordered from smallest to biggest.

So what do the British ‘people’ agree on? Economic issues. They think inequality is too high and that the rich are treated better than the poor. Where do they disagree - social issues, especially the death penalty, whether they are listened to, and ho ho ho building houses.

Put differently, to the extent that there is a coherent ‘people’ out there, they agree on economic issues. They disagree more on social issues and whether they feel represented. This is, it must be said, not brilliant supportive evidence that there is a socially conservative ‘people’, faced off against a ‘new woke elite’. It’s pretty good evidence that the British public are deeply torn internally on social issues and on whether they feel represented.

In other words, politics happens among the people, not to the people.

Are the Elite even Different?

You might fairly argue that the new woke elite argument isn’t about differences among the people - it’s about the unrepresentative views of the wealthy educated professional class. OK, so let’s do that.

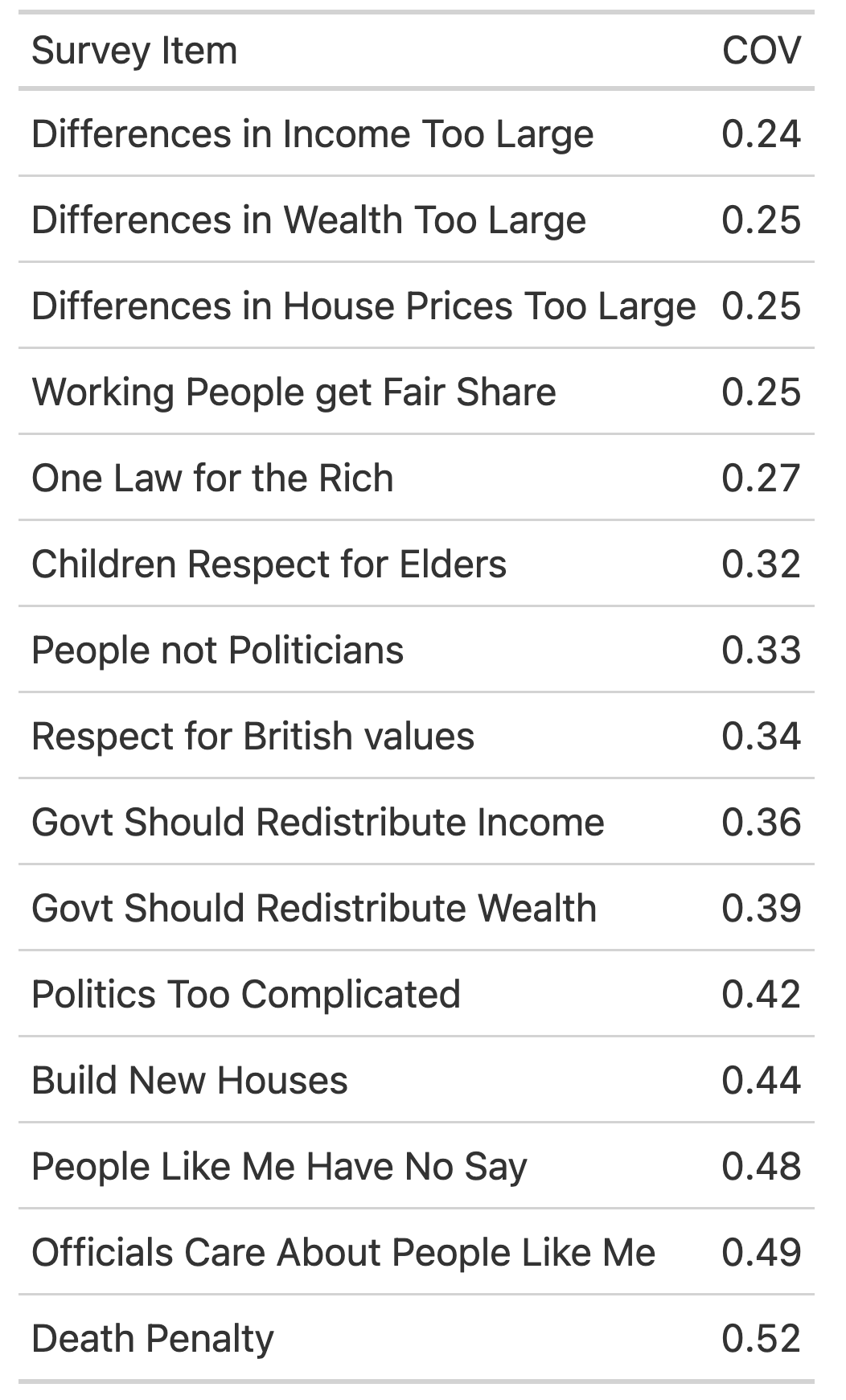

To avoid drawing ten-dimensional plots (which you know I would love) I am now going to use a classic statistical technique to reduce dimensionality called principal components analysis (PCA). Essentially, I am going to throw in twelve of the above questions into a pot and look at the variation among them (I’m taking out the three efficacy questions because they were randomly ordered in the survey). Then the wizardry of PCA extracts the two dimensions that explain most variation (which are essentially each weighted averages of the 12 questions).

It turns out that these two dimensions explain almost sixty percent of all the variation in the 12 questions. Which is nice.

The first dimension basically picks up the economic-style questions - particularly the ones on inequality and redistribution and whether working people get their fair share. The second dimension picks up the social conservatism questions - death penalty, respect for British values, and children’s respect for elders. The questions on people versus politicians and ‘one rule for the rich and one for the poor’ get split between the two dimensions, a little bit more towards the first one.

So we have an economic dimension and a social one. And now we can map the British people. I have about 3000 respondents who we can analyse here. And what I am going to do is to split them by groups and plot their average views on the economic dimension (where right means more conservative) and the social dimension (where up means more conservative).

I am going to do this in the style of a YouTube unboxing, adding groups one at a time. You’ll see why. Let’s start with gender differences. There aren’t really any.

Once we add age, we do see something. Something pretty expected. Older people are much more economically conservative than young people and quite a bit more socially conservative too.

As our final demographic, I add ethnicity. Need to be a bit careful here because some of these groups only have around forty members. Still, it’s important to note that White British people are right in the middle (which we would expect since they are a massive majority) - they are not massively socially conservative. Indeed the only ethnic group that is relatively socially conservative is Black British. The most socially liberal ethnicities are Other White (many of whom will be EU citizens) and mixed race (the youngest ethnic group).

OK, let’s start finding possible members of the ‘new woke elite’, who I will colour in red. What about degree-holders? Well they are indeed more socially liberal than non-degree holders. But both are essentially equidistant from the centre (which makes sense given they make up about half the sample each). Who is less representative then? Neither.

Now I add two things - housing tenure and employment status. We are widening out our scatterplot a little. But notice the more extreme groups - social renters and students are now anchoring the social axis. I think we all would have been a bit surprised if students had not been the most socially liberal. But social renters and then unemployed as the most socially conservative? Note that the employed and those with mortgages are all quite socially liberal on average. Them that works…

Now let’s put in another elite group. I am adding household income now - breaking it into four similarly sized groups. And here we see something a little surprising. There is no relationship between household income and economic attitudes and a very strong one with social attitudes. LOL. And yes the richest households are the most socially liberal group so far. A new woke elite??? Well I suppose they are indeed as unrepresentative of the British public as social renters and the unemployed.

The next figure adds social grade - ABs vs CDEs. And here it looks a lot like what we saw with degree / non-degree. ABs - presumably part of the new elite - are more socially liberal than average, but not much more so than CDEs are more socially conservative than average. Meh.

And let’s add one more dimension of eliteness. Occupation. Using the NS-SEC definitions of occupation, I think managers and professionals are probably the two elite groups. And again, they are more socially liberal than average. But no more so than blue collar workers (skilled or unskilled) are more socially conservative than average. Who is less representative of the people? Neither.

So far we have seen that the ‘elite’ groups coloured in red are definitely more socially liberal than the average Brit. So I suppose that is some supportive evidence for the ‘new woke elite’ hypothesis. But here’s the thing, there are an equal number of groups that are equidistant from the British average, just on the socially conservative dimension. The British public is split. There are some groups - middle income people, clerical/admin workers - that are right around the middle. Everyone else is more divided. There is no ‘people’. Just lots of people.

But now here’s the trick. What about looking at the average positions of people by how they voted in the 2019 General Election? I have coloured the parties in blue. And… well just look. Except for the Lib Dems (LOL), the partisan placements are all at the extremes of our graph. The Conservatives and Labour pretty much anchor the left-right economic dimension. Brexit Party supporters are miles away from everyone. Greens, Plaid and Lib Dems are all socially pretty liberal.

Let me state this again. The differences in opinions in the UK are not from demographics - they are not about where you work, or how much you earn, or how you were educated. They are about which political party you support. And that could be because you sort into parties based on your ideology. Or because parties drive how people form their ideologies. But what leads to extreme views distant from ‘the people’? Supporting political parties.

And actually, these averages hide huge differences anyway. There is no British people with a view that the elite are somehow violating because there is no coherent British public will.

Here is a scatter plot of everyone in the survey (the funny diagonal shape is because of how PCA works). Notice how much variation. there is compared to before - the scales of the graph have more than doubled and people are situated everywhere. The graph below colours people black if they don’t have a degree and grey if they do and the red letters show the averages from before. Individual variation massively dominates average educational differences. There are grey and black dots everywhere. In fact the only place where we see a lot more grey is not in woke elite central - the bottom left - but in Trussville - the bottom right.

If we now do the same graph but colour the dots by Conservative versus non-Conservative voters you can see there is much more separation between the dots. The greys are much more prevalent on the right. So parties do form an important role in guiding and channeling opinion - I’ve been calling them ‘chaos cages’. But that means polarisation.

Stop Trying to Make the Will of the People Happen

The key message from the figures above is that there is no obvious evidence from survey data of a woke elite that is particularly different from the rest of the public. And the one thing that makes people diverge is voting for a political party. Our differences are political, not demographic or educational or professional.

And that leads me to the title of the blogpost, which is an inversion of William Riker’s classic book Liberalism against Populism. Riker, a scholar of social choice, denied the possibility of a true ‘will of the people’ because of the impossibility of being able to truly aggregate individual preferences. To read all about Arrow’s impossibility theorem, the Condorcet Paradox and the politics of chaos more generally, I refer you to - psych - Why Politics Fails, where I discuss this in the chapters on democracy.

Riker argued that the populist idea of a true general will was doomed to fail because no such thing could be coherently crafted. Instead ‘liberalism’ was about managing inevitable differences and developing institutions that constrained, bound, and channeled these disagreements. And the existence of political parties for thinkers in this tradition is to manage disagreement in this fallen world, where there is no such thing as the ‘will of the people’.

That we all disagree is unavoidable. There is not a people with coherent views that we can contrast to an elite. The people are diverse, disagreeable, chaotic, divergent. They are humans.

Our party politics may be frustrating and polarising. I agree! But pretending that there is an elite out there that, in the words of Nick Timothy, must be ‘crushed’, so that the people’s will can have its way is frankly silly. People are complex and sophisticated. If only the arguments made by commentators in our national press were also so.

All this is pretty clear and on point, and undoubtedly correct in terms of the two, allow me the phrase, old-fashioned social and economical "left" and "right" .

But i don't think "woke" in "woke elites" is described even the very ends of the items traditionally used to measure "social left".

I think to measure that and to capture the division between "woke elites" and "the people" you'd need a new set of items, a subscale of "woke" that whilst UNDOUBTEDLY highly correlated with "socially liberal" goes well beyond that.

It would consist of items almost exclusively related to race and gender and use of language in social interactions. Off the top of my head: There are only two genders; It's impossible to change your biological sex; People should use toilets and changing rooms according to the gender assigned at birth and their genitalia and not according to how they identify now; Using certain words for groups of people causes as much harm as physical violence; Women never make up accusations of rape; No person ever says "now" when propositioned for sex but actually wants to be pursued; Racism is still constantly present in the British society; All White people have racist attitudes even if they not realise it themselves; The role of exploitation of non-white people in the British history must be emphasised much more than it's now; All non White people in Britain regardless of wealth and education suffer prejudice and barriers to success; We need to remove statues and plaques to any historical figures who benefitted or were involved in the slave trade even in a small way; Black people from the Caribbean should be paid reparations for slavery their ancestors endured; It's ok to forbid any speech that's racist, sexist or homophobic; etc.

I think if you look at those issues you'd see a much more extreme clustering of attitudes with the "woke academic thought elite" at odds with the majority of "the people" (apart perhaps from some students largely of humanities) -- even those who otherwise support the "traditional socially liberal" set of values.

I'd like to see the dots sized by what percentage of the population they represent. Contrasting certain groups that represent quite different fractions of the population as being equally far from the centre in different dimensions seems to miss something. For example, in the plot highlighting "occupation", he contrasts managers and professionals with blue collar workers and asks which is more unrepresentative; yet actually *al*l of the occupations he shows are more socially conservative than the average (some a little, some a lot) *except* managers and professionals, so I'd probably hesitate to definitively dismiss the argument that these two groups are in a real way more unrepresentative than blue-collar workers. I still find the argument mostly convincing, I just think there are nuances to it that are missed by not showing that dimension.