As promised a couple of weeks ago, this post is an interview with my colleague Mike Albertus, who is Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago. Mike has written a brilliant book on the politics of land that just came out (UK here, US here, as ever with slightly different covers!). Mike has written some of the most interesting academic articles and books on the politics of land redistribution, particularly in Latin America - this is his first foray into writing for a wider audience. You can subscribe to his own Substack here. Since in my own work on both democracy and housing I’ve touched on related topics, and what with Donald Trump engaging in sum… uh… land speculation with other people’s land… I had a few questions for him…

1. What's the one-liner for the book and what motivated you to write it?

Land is power: choices from the past about who should own land and how they could use it have deeply shaped modern societies in underappreciated ways and today’s choices will shape our future.

2. Do we talk enough about land, or does it go under the radar in politics?

We should talk about land a lot more! It’s central to zoning and the housing crisis, property taxes to fund schools and social programs, resource extraction and environmental regulations, patterns of racial segregation and racialized policing, what we eat – through food markets and agricultural subsidies, and much more. Land is also the world’s most valuable asset at some $200 trillion.

How land is used has big externalities. Think about the fact that half of all land in the American West is owned by the government as parkland, forest land, and more, providing recreation opportunities and revenue while also protecting biodiversity and fixing carbon. The same isn’t true in the East or Midwest. Meanwhile, building on land that is subject to climate risk, whether in low-lying coastal areas of Florida or in wildfire prone areas impacts insurance markets for everyone and can lead to using public dollars to subsidize risk whether through FEMA rescues or the National Flood Insurance Program.

Who can own what land, how, and subject to what restrictions varies drastically around the world. While land is important everywhere, how it’s important differs and understanding that is key to the politics of a place.

3. Your work has traditionally focused on land, mine on residential housing. Are these two sides of the same coin and when we talk about housing are we really talking about land?

We can’t really talk about housing without talking about the land that it’s on. I wrote a piece recently about how the current housing crisis is really a land crisis. The price of land has risen more rapidly than housing and now makes up about 40% of the share of property value in the US. In a growing number of US and UK cities and metropolitan areas, land prices constitute more than half of property value, and in areas like San Jose and Los Angeles they make up around three-quarters of land value.

But differences in the severity of the housing crisis across developed economies illustrate the importance of the politics – and the prices – surrounding land. Take the United Kingdom, which faces spiraling prices and a deficit of 4.3 million homes that is worst in the most dynamic and desirable areas. The UK has discretionary case-by-case urban planning rather than rule-based planning, which means that both urban planners as well as city councils can reject building plans. That gives city councils a political role in choosing winning and losing developments, and it encourages residents to lobby to protect their particular interests. As a result, most houses are built in the areas where circumventing these dynamics is easiest, such as far urban peripheries. And land prices continue to rise.

Japan has taken a different path. Property prices in Tokyo were the most expensive in the world thirty years ago. No more. Affordability has not come because of population decline. Greater Tokyo’s population increased by 4 million people over the last thirty years. Instead, urban zoning is simple. There are twelve zone types, each defined by a nuisance level they allow that ranges from residential to industrial. If the building type doesn’t exceed the nuisance level, then anything can be built. That circumvents a lot of planning and permissions for individual sites and makes it far easier to increase housing density where there is the greatest demand.

The United States is more similar to the UK in its land politics and policies than to Japan. Most locales, especially cities, have byzantine land regulations and zoning restrictions that make homebuilding slow and expensive. Some of these are rooted in politicized racial and demographic changes that existing property owners have tried to forestall through restrictive land use regulations that the Supreme Court allowed beginning in the 1920s. Strong property rights in real estate support the owners of property but they also serve to keep other people out.

While land is key to understanding housing, the flipside isn’t as true: you can talk about land without talking about housing on the land. Questions of territorial sovereignty, community and group identity, agricultural production and food systems, and environmental protection all deeply implicate relationships to and management of the land but housing is not central to them.

4. In the book you connect land to a series of questions that touch on questions of identity - race, gender, and so on. Can you explain the connection and what we didn't know before reading your book on these questions?

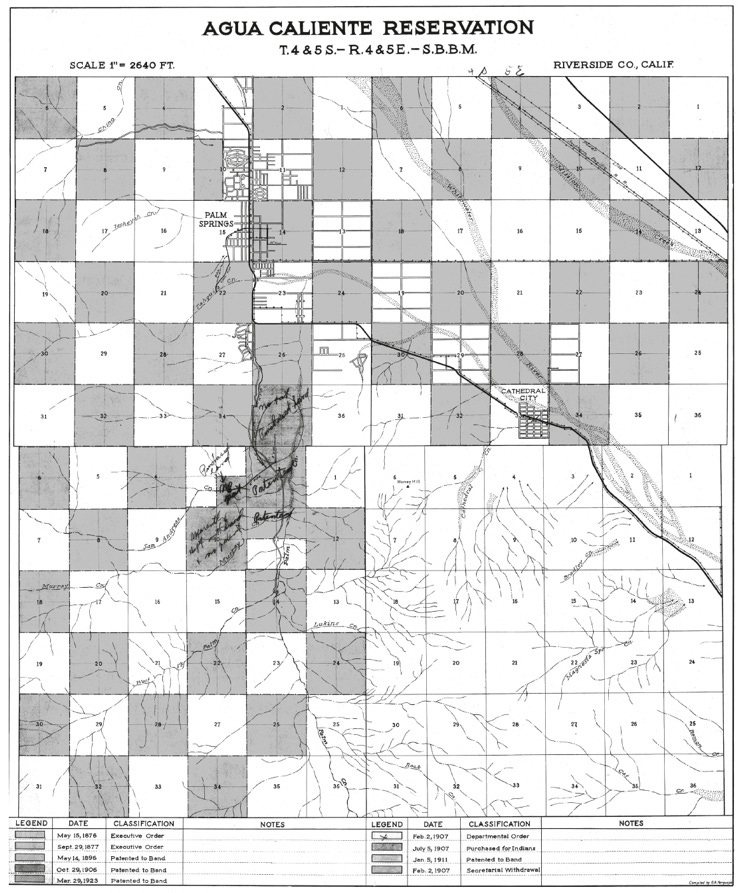

The social, political, and economic power of land means that it cuts deep ruts within societies along major identity markers like gender and race. One story I cover in the book is linked to the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians in southern California. Like many native American communities, land reshuffling in the American west for them meant land dispossession. The US government forced them into a lopsided treaty that ceded much of their land in 1852, and then gave the Southern Pacific Railway a right of way through their remaining land. Because railroad land grants at the time gave every other square mile of land to railroad companies in order to help them fund laying tracks, the Agua Caliente reservation was created as a checkerboard of land where they got every other square mile of land (see map). It was a cruel and effective way to break down tribal cohesion and the community. And it was part and parcel of creating a new racial hierarchy in the American West, dominated by white settlers. Without land reshuffling, it’s hard to see how that same sort of rigid hierarchy could have been so effectively imposed.

One example of land ownership and gender comes from Canada. Like the US, Canada had a homestead act that doled out millions of acres of land to settlers from the 1870s well into the 1900s. But unlike the US, it didn’t allow single women to homestead. Patriarchal social norms and fears that women wouldn’t be as productive as men on the land held women back. The result was that men won almost all western land through Canadian settlement. We see that disparity in health and income statistics many decades later in prairie women in Canada, and some of that has been brought to cities.

Another example is Bolivia. The country had extreme landholding concentration dating back to the colonial era up until the 1950s. A revolution sparked reshuffling of that land into the hands of indigenous peasants who worked it. But like in Canada, the land went to men and entrenched patriarchy. However, few people received formal property rights to the land. When Evo Morales and MAS came to power in 2006, they started formalizing land. Their indigenous social base empowered women to a greater degree than prior ruling coalitions. In fact, the leader of the new constituent assembly charged with drafting a new constitution was the social activist Silvia Lazarte. They started titling land jointly to women. It was deeply empowering.

Indigenous women like Lazarte took positions of unprecedented political power alongside men and gained a stronger voice in community governance and affairs. Discrimination against women, particularly in rural areas, remains considerable in the country. But respect for women, their ability to have a say in household affairs, and their ability to work alongside men in positions of power and authority have advanced in ways that would have been hard to imagine as recently as the early 2000s. Land is a cornerstone of this historic shift.

5. Another big theme of the book is the connection of land to climate change - something that is more familiar - but how does your book move beyond the consensus?

Land power determines how we treat the environment and shapes the trajectory of climate change beyond greenhouse gas emissions and global climate accords. That happens both indirectly – by shaping development and consumption – and directly.

Take countries like Japan and South Korea, both within the top 8 carbon-emitting countries since the 1960s. In the years after WWII, both countries adopted sweeping land reform programs that transferred land from landlords to their tenants in small, family-sized plots. The governments of these countries followed that up with generous inputs and subsidies, and within a generation families were sending their children to schools rather than the fields. It completely rewired these economies by supporting urbanization and industrialization. That was great for development, but bad for the environment as these countries became big carbon emitters and their citizens bought and consumed more things (like cars).

Land power also has a more direct impact on climate change through how it has shaped patterns of human settlement and land management over the last 200 years. Take the example of Brazil. Extreme landholding concentration from the colonial era persisted into the 1960s and fostered an effort under democracy at reallocating land in settled parts of Brazil. Large landowners teamed up with the military to topple democracy and install a military government. That government then tried to reduce land pressure on valuable estates by instead opening up the Amazon rainforest to settlement and agriculture. Some of the biggest hotspots of deforestation in the Amazon today are around land settlements from the military era. It set in motion a process that cannot be easily stopped and that is expected to tip the Amazon into a death spiral within the next decade that will shift world weather patterns and accelerate climate change. Meanwhile, laws protecting “productive” property from reallocation in more settled areas encourage landowners to clear land and put cattle on it to demonstrate land use, which again accelerates climate change.

China’s massive land reform and experiment in collectivization in the 1950s-1960s unleashed a similarly catastrophic amount of deforestation that even initiatives like the Great Green Wall – an effort to plant billions of trees to hold back the expanding Gobi Desert – can’t erase.

A different story unfolded on the US prairies. There, settlers tore up native grasslands to plant grain crops. Most famously, this contributed to the Dust Bowl of the 1930s. But soil and watershed degradation didn’t end with new plowing techniques. Today topsoils are far thinner than pre-settlement times and can’t fix carbon like they used to. (This is something that regenerative agriculture aims at reversing, but it remains very niche within our food systems.) At the same time, agricultural subsidies to the “Big Ag” farm lobby have resulted in some 30% of US land being used for grazing and growing feed for cattle (meat and dairy together count for some 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions).

6. We can see in the early days of Trump 2.0 an interest in territorial expansion (to Greenland, the Panama Canal, and maybe even Gaza and Canada). Putin of course invaded Ukraine. Political scientists and IR scholars had often argued that sovereign wars over the control of land were passé. Were we all wrong? And if so why?

The post-World War II era and particularly Cold War-era competition over influence in the developing world ushered in an unusual period of territorial stability when viewed from the perspective of the last few centuries of human societies. But the biggest drivers of the demand for land and territorial acquisition – human population growth and state-making – haven’t stopped. The global population is heading toward 10 billion before the end of the century. At the same time, the consequences of climate change are now right around the corner and we have seen the beginnings already in events like supercharged Florida hurricanes and the ever later rainy season in Southern California that lined up drought with the Santa Ana winds and fueled the LA wildfires. The melting of Arctic ice is going to open up new northern shipping routes in the coming decades that will reroute global trade.

Three things are lining up here: a population crunch, more powerful states than the world has ever seen, and drastic upcoming changes to the areas that will be attractive to live and patterns of economic activity. That is going to set off a competition to grab territories with weak sovereignty and to lay claim to up-and-coming strategic areas, whether they be in the oceans, on remote islands, places like Greenland, or Antarctica.

7. Is land still relevant when America's largest companies make their money from social media, operating systems and AI?

Land is foundational even in an economy that moves away from agricultural labor. It hosts valuable resources and strategic value. It’s needed for placing data centers and solar arrays. Vast areas of land are still needed to feed populations, especially for land-intensive food like meat and dairy. As mentioned above, land also makes up about 40% of the value of housing, and more in some places.

Land remains the world’s most valuable asset and it continues to appreciate considerably. That is reflected in the post-Great Recession rise of institutional investing in land and billionaires like Bill Gates owning land, which treats land as a market commodity but also shows the enduring attractiveness of land – and land power.

8. Is it land that matters or the materials in it?

The resources on land matter, for everything from harvesting timber to extracting minerals like oil, cobalt, and gold. But land is far more than that. The location of land also matters. Consider the fact that land is vastly more expensive per acre in attractive urban areas than in far-flung rural areas regardless of the type of land. In a similar fashion, land can also have strategic value because of its location or what it can be used for.

It goes beyond this as well. A connection to land provides people a sense of who they are in the world and the communities that they belong to. You can see that in the pride that people have in their towns or cities, their connection to landscapes, and their sense of rootedness in place. It’s also linked to social status and power. The nobility of Europe are an extreme example. Kings, dukes, and earles all had a basis of power in their control of land, and many had the names of those lands in their very titles. Think of the House of Windsor in the UK, whose name comes from the Windsor Castle estate. They also control the Crown Estate now, a massive agglomeration of about 200,000 acres of farmland, urban real estate and forests.

Land is a valuable asset for building intergeneration wealth. It has historically been a marker of citizenship and continues to impact political power (think of voices in debates over zoning for instance or town hall meetings). It is linked to social prestige and the projection of importance and clout (Yellowstone, anyone??).

9. Do you think it's likely we will see a resurgence of land tax policies a la Henry George? Why or why not?

There is a resurgence in interest in George’s ideas around land taxes that date back to the 1890s. The core idea is that land derives a lot of its value from its location and the surrounding community and that the community should benefit from that as values rise. His proposal was to tax the value of land but not improvements on it. Some proponents of George think that there should be a single land value tax and that other taxes can all go out the window.

Some places have experimented with this idea, like Arden in Delaware, but there haven’t been many takers. One case that a lot of people are watching now is Detroit, where the mayor Mike Duggan has proposed a land value tax. The problem there is that the city has lost the majority of its population since the 1950s, generating a large patchwork of vacant land and blight. Since the 2000s, investors have bought up big tracts of the city and mostly sat on it, waiting for others to build there and the value of their land to appreciate. A land value tax would penalize that sort of behavior and favor people who want to acquire land to build on it and redevelop the city.

A successful experiment in Detroit would mean a lot for the Georgist movement. But it has been slow. State approval is required for the change and it has been delayed repeatedly. Then Detroiters would have to approve it. That’s one of the biggest hurdles for the land value tax idea: land tax policies are local and getting people to change something as consequential as property taxes is notoriously difficult.

And while a land value taxes could make good sense in a place like Detroit, the housing problems in most cities come from a lack of supply, which is the opposite problem that Detroit has.

Many thanks to Mike for taking the time to answer my, often self-interested, questions!

In the first paragraph of the answer to Q3, there is a statement to the effect that in certain areas land prices are three-quarters of land values. Should that be three-quarters of property prices?