In Whose Interest?

The Substack Is Back! What will be the political effects of rising interest rates? And of the policies that might offset them?

You don’t get around to writing a Substack for a few weeks and then the Bank of England comes along and blows up the housing market. Maybe. Serves me right for my tardiness. Anyway, we’re back with another data-rich look at British electoral politics. And I hope a couple of other posts in the coming weeks. Wish me luck.

Oh, and a few book updates. I’ve been talking about Why Politics Fails at various festivals, attempting not to overheat during our recent heatwave. Sadly you won’t get to see a video of me sweating in a tent at the Kite Festival or in the beautiful-but-greenhouse-like Felixstowe Harvest House. But if you’d like to see a great Tortoise Think-In I did with the brilliant Cat Neil and Giles Whittell (and a bunch of keen Danish journalists) you can watch here. And there’s a fifteen minute Book Bite about the book I did for the Next Big Idea Club here. Thanks also to the kind folk at HMT and IPPR for hosting me for smaller events.

And remember, politics is still failing, so you have to buy the book until that stops.

Five Percent Points, Andrew, That’s Insane

Do you remember early 2008? A halcyon time. An era when Taylor Swift, Beyoncé and Rihanna topped the charts. When punters salivated about a groundbreaking new Christopher Nolan movie. When, the fourth season of a Jesse Armstrong comedy had just aired and critics demanded a fifth. And when the Bank of England set interest rates at five percent. Plus ça change.

I remember this era quite well because I bought a house at an interest rate of about five and a half percent. Since I was in America, it was a thirty year mortgage, which I guess I would be halfway through about now. At the time, other people with worse credit were being charge substantially higher rates (the famous subprime mortgages) - or coming off low ‘teaser’ rates onto nosebleed-inducing interest payments.

The superannuated among my readership will recall what happened next. Things went south, fast. I spent the peak weeks of the credit crisis, as the US Senate frantically voted against and then for a bailout bill, in the surreal dreamscape of Silvio Berlusconi’s Italy. Berlusconi (RIP, I guess) occasionally addressed the Italian public on TV, hinting that something concerning might be happening abroad, but don’t worry your little heads about it, everything will be fine…

Of course it wasn’t fine. Not for Italy or anyone else. Housebuyers in America and Europe alike couldn’t afford their mortgages when teaser rates reset. So they defaulted, leading to a wave of foreclosures that further tanked the housing market. And then the banks. And the insurance companies who had underwritten the mortgages. And underwritten the securities backed by mortgages. It was bad. Both for average citizens. And for politicians.

So, Mr Sunak, how are you feeling?

There is at least an important difference with 2008 today. The Bank of England had reduced interest rates to five percent in early 2008 and was about to send them asymptoting to zero like a festival of Zeno’s paradoxes. This time, interest rates are rising. And aren’t coming down any time soon. Our problem is not (yet) a lack of liquidity and solvency in the housing and financial markets. It’s an overheating labour market, combined with a cost-push created by the end of the COVID lockdown and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Rates rising means the political economy of five percent interest rates is going to be quite distinct from 2008. Then the problem was an over-valued housing market with subprime mortgages, very high loan to value ratios, lots of interest-only mortgages, an assumption that house prices only ever went up and many over-exposed financial companies. It was the interlocking bad bets made in the finance sector plus the waves of foreclosures that set off the recession.

Our problem now is slightly different. By and large, I think we can expect much lower levels of foreclosures. Although it’s true that part of the crisis will be people moving off very low interest rates to much higher ones, this time they were at least ‘stress-tested’ on the possibility of higher rates when they got their mortgages. Most people should be able to afford the increase in interest rates coming their way, without being foreclosed on. But, it is going to be a horrendous squeeze on living standards as most mortgage-holders face payments increasing by several hundred pounds a month.

Rishi Sunak is caught in the headlights here. The Bank of England has been independent for a quarter-century now. The Prime Minister cannot directly influence the bank rate and the mortgage rates that build off that. And indeed, independence of the Bank of England would be meaningless if it were attacked or abandoned the moment the Bank had to make a decision people didn’t like. It’s true that Sunak does have tools on the fiscal side he could use to reduce inflation (and thereby hope the Bank is more lenient), but these are all super costly, economically and politically - increase taxes, cut public spending, refuse to allow public sector wage increases.

So, given the Devil is even worse than the deep blue sea, Sunak is going to spend the last year and a bit remaining of this electoral cycle in a world of high interest rates and cries to help mortgage-holders. Cries he will probably have to ignore, at least in terms of a bailout, which would both undermine the Bank’s strategy and be incredibly expensive.

And this leads us to the political consequences of Mr Bailey. We can think about the interest rate rise in two ways. Where it’s going to hurt. And who it’s going to hurt. Neither looks great for the Conservative Party’s chances of re-election (you did not, I’ll warrant, need a political scientist to tell you that). But Labour too are not immune from the fallout - not least because chances are they will have to deal with it.

Where’s it Gonna Hurt?

If you were to point at the part of the body politics where it hurts most, the answer would be Wokingham. Poor poor John Redwood. Oh well.

Wokingham, like parts of Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire, Surrey and Cheshire, has very high rates of mortgage-holders. Around forty-percent of people in some of these areas own with a mortgage. You can see from the figure below that the percentage of people across parliamentary constituencies who are mortgage-holders varies between ten percent - the most expensive parts of London, and forty-percent, with the median constituency coming in just under thirty percent. Given how much more likely homeowners are to vote (about fifteen to twenty percent points higher than renters), this means that in many many constituencies, mortgage-holders are going to be crucial, possibly swing voters.

We can also see what a problem this is for the Conservative Party in particular. There is a clear positive relationship between the vote for the Conservative Party in the 2019 General Election and mortgage-holding (this is England and Wales only btw). For the nerds among you, the fit is not super-tight (an R squared just under a quarter) but the relationship is highly statistically significant at the bivariate level (t-value of 13!).

Still, we do see some very Conservative, very ‘East Coast’ places with quite low levels of mortgage-holding (Clacton, Boston, Louth). And that’s because those are places with lots of old people and cheap property - so people own their houses outright. As we’ll see in a bit, this is an important cleavage for the Conservatives.

Labour too, hold some constituencies with highish mortgage-holding, especially around the big cities of the North. So Starmer and Reeves can’t pretend not to worry about people with mortgages either. Again, we will come back to this.

Because reading overlapping constituency names is painful and I don’t want to create a run on opthamologists, let’s look at a simpler scatterplot, with the colours denoting the 2019 winner. Again, it’s just England and Wales (sorry but the Scots don’t release comparable housing-tenure data, what with them having a different Census…). Here is the last figure, just with dots. Much more soothing…

I mentioned earlier, the outliers on the right of the figure - generally seasidey locations on the East or South coast. The reason places such as Christchurch, Clacton, North Norfolk and so forth have low mortgage-holding is because in these places fifty percent or so of people own their property outright. For old time’s sake, let’s do one more with names. Yikes. That’s a pretty tight fit (an R-squared of over 0.4). Pretty much everywhere (that’s not in Wales) where outright ownership is high is a Conservative seat.

Here we can see that in pretty colours again. Those dark green colours in the top-left are Plaid Cymru constituencies. You can also see here that the variance of the scatterplot decreases as we move to more Conservative constituencies. Put bluntly, Conservative constituencies are homogeneously full of outright owners.

And, ta-da!, here’s what happens if we look at mortgage-holders minus outright owners. There is actually a negative relationship between this difference and the Conservative vote. Labour are basically split either side of zero (equal numbers of outright and mortgaged homeowners). But the Conservative Party’s base is one where, by and large, outright owners massively outnumber mortgage holders.

So if I’m wondering what political incentive there is for Rishi Sunak to do something ‘big’ for mortgage-holders, especially something that might cost outright owners (through taxes or, GOD IN HEAVEN FORBID, lower property prices), it’s not clear to me that there is in fact any such incentive. Let them eat interest rates.

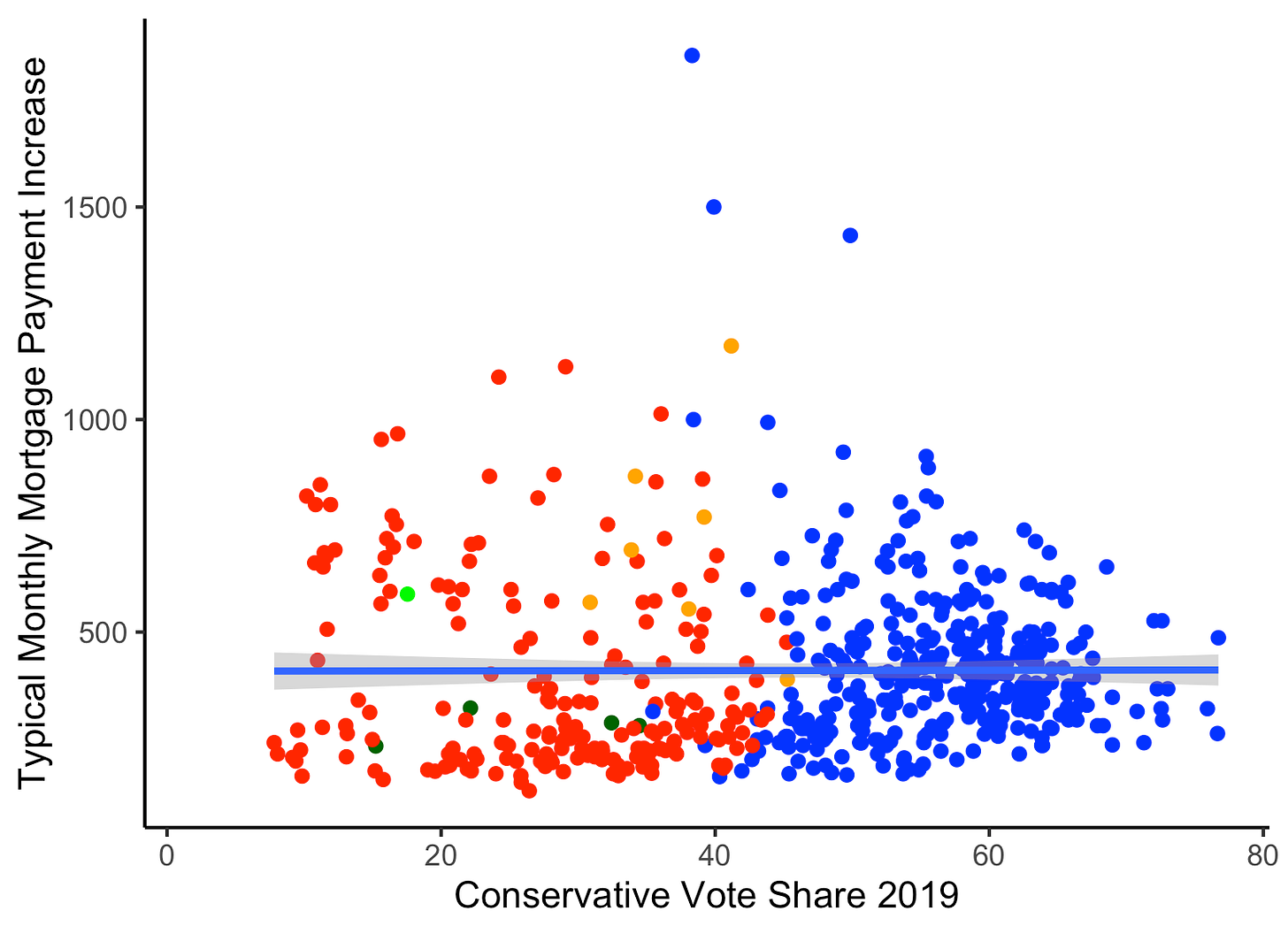

We should be careful here. Not all mortgages are the same. Places with expensive property are likely to have expensive mortgages, where an interest rate increase really affects the family finances. Perhaps the Conservatives are affected here? Not really. In the graph below I calculate - in a full back of the envelope fashion - the monthly expected increase in mortgage payments, assuming a four percent higher interest rate (i.e. from say 2% to 6%), on a property that has forty percent left to pay in the mortgage. I take the latter from my own survey estimates where people told me the estimated current value of their house and how much left they had to pay.

So, for each constituency, I take the median house price, multiply it by 0.4 (the mortgage to price value), then again by 0.04 (the interest rate increase) and then divide it by twelve. That’s Numberwang.

That gives us this pretty picture here. The typical increase in monthly mortgage payments is in the low hundreds (about £350 per month, which is ouch). In other constituencies this gets much higher. This is pretty close to some of the estimates floating around over the past few months. But who knows? The key thing for political science purposes is that there is no obvious political relationship. Mortgage-holders in Conservative seats and those in Labour seats face similar monthly payment increases on average.

Remember, though that the proportion of people with mortgages varies across constituency. So if we aggregate up, taking the expected payment increase and multiplying it by an even madder guess of how many mortgage-holders there are on the electoral register of each constituency, you get this.

We are now back to a slight positive curve - that is, because there are more people in Conservative constituencies with mortgages, the total extra money going to pay the bank is higher in those places. But this is not a scatterplot I would… um… bet my house on.

Now you might wonder — perhaps because you don’t only care about the fortunes of property owners you deeply un-British monster — what these patterns look like for renters. I’m glad you asked. First off, private renters. Here we see a fairly stark pattern - people in Conservative constituencies don’t tend to be renters. They might of course be buy-to-let landlords owning properties in Labour constituencies. Such are the wicked webs we weave. But the meagre amount of renting in Conservative constituencies helps explain why renters rights are not high up the Tory wish list.

And for social renters things look pretty similar, perhaps even stronger. Even with the death of the Red Wall and the victory of good old Boris, it wasn't really constituencies with lots of social housing that shifted from Labour to Conservative. But prepare yourself for a statistical mindstorm…

Who’s it Gonna Hurt

I left you just now with a pretty strong negative geographical relationship between social housing and Conservative voting.

Now let me tell you all about the ecological fallacy. Or Robinson’s paradox. What correlates one way at the aggregate level (constituencies) can go completely the other way at the individual level (voters). Geography can trick us about people.

You see, the Conservatives did rather well with voters in social housing in the 2019 General Election. In fact, Old Etonian, gallivanting dilettante Boris Johnson beat donkey-jacket wearing socialist Jeremy Corbyn among people living in social housing.

Well, at least according to my survey. Long-time readers of this Substack will recall the various surveys I ran with YouGov in 2021 and 2022. Here, I am using nationally-representative data from October 2022, about 3600 hundred people in the UK (including Scotland! but not NI in this case). And I can break out how people voted in 2019 by their housing tenure.

Looking at the bottom right box of the figure below you can see that the Conservatives had an 8.7 percent lead on Labour among social renters. In fact, Conservatives did better in that group, absolutely and relative to Labour, than among mortgage-holders. Wow. Of course the Conservatives decimated Labour among outright-owners. Labour only led among private renters.

All of this tells us much we might have suspected already. The Conservative coalition was built first and foremost on age. Older people are more likely to own their houses outright. And they are more likely to have secured social housing in the past and still be in it. And they liked Boris and Brexit, hated Corbyn and Remain, and there we are.

Still, in 2019 the Conservatives did lead, albeit marginally, among mortgage-holders. What about now?

Ahhh. The next figure shows the vote choice estimates from my respondents in late October 2022. Labour had a huge lead in that survey. Over twenty points. Sunak was able to close this gap somewhat over the following months. But the eagle-eyed among you will note that the current gap in vote intention is also over twenty points in many polls. So, I’m still going with this survey! The Conservatives declined among all groups from GE 2019 to the Oct 2022 vote intention. In fact, by more among outright owners and social renters than mortgagees or private renters (though that may be ceiling - or rather floor - effects among private renters).

Labour in October 2022 had a ‘majority’ among all groups except outright owners - and even here they led very marginally. And a world in which over half of mortgage-holders vote Labour is one where Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves will have to pay very close attention to their turmoil.

When we split our mortgage-holders into two groups, by those who say their mortgage remaining is less than half their estimate of their house’s value versus those who owe half or more, we see a stark stark divide. Labour lead the Conservatives by FORTY-THREE PERCENT POINTS among those owing more than half. They are basically like private renters.

Now whether this is because these are younger people more likely to vote for Labour normally or because the Trusstravaganza and its effects on mortgage rates spooked them, I don’t know. But the Conservatives are not winning this group. They are Labour’s base - and Labour’s problem.

Let me finish by flipping these analyses around. Here I break voters up into particular political groups, as I have done in a few previous posts. I look at five core groups (sorry everyone else!): people who voted Conservative in 2019 and still intended to do so last October; those who voted Conservative but moved to Don’t Know; those who switched from Conservative to Labour; those who voted Labour and were sticking with them; and those who didn’t vote but intended to vote Labour. These are the five largest groups in the electorate.

This time, I’m not looking at their preferences but their housing tenure. Let’s start with the proportion in each group who have a mortgage. The only real stand out here is that loyal Labour voters are more likely to have a mortgage (they are younger, I guess).

But now if we look at the group who owe more than fifty percent of their house’s value we see something interesting. Labour loyalists still lead, but look who is next - Conservatives who have switched to Labour. So again, this is where Starmer is making up ground and why the interests of high debt mortgagees are crucial for Labour. The disaffected Conservatives (Con-DK) by contrast score the lowest among these groups. Sunak isn’t winning these folks back with mortgage relief.

Turning to those mortgagees with less than fifty percent to pay we see the loyal Conservatives the largest group. And the non-voting (or too young) Labour supporters are least prevalent.

What about outright owners? Well looookeeee here. A nicely decreasing set of bars from the most loyal Conservative to the discontent to the switcher, to loyal Labour to newbie Labour. I can’t look at this figure and really believe that the Conservative base are going to care that much about mortgage rates. Indeed, they are going to get the nice savings accounts rates that have been a perennial complaint of Daily Express covers for over a decade.

And what about private renters? Again L.O.L. And they say that politics is unpredictable and contingent. Yeh, maybe. But not here. Only around seven percent of loyal Conservatives are renters. And half of them are current Conservative Party nominees for Mayor of London. By contrast a quarter of newbie Labour voters are renters. So if I’m Labour, I start thinking about protections for renters as a politically smart move.

Finally, what about our friends, the social renters. Remember how many voted for jolly old Boris in 2019. And that the Conservatives had a sizeable lead among social renters. Well… don’t look now guys but I don’t think that’s going to hold. The Conservative to Labour switchers are disproportionately social renters, at least as compared to other 2019 Conservative voters and even 2019 Labour voters. So, while I don’t expect Rishi Sunak to be rolling out policies for renters in the private market, this feels like a group who he needs to win back and for whom one might be able to design attractive policies (even if it is something along the lines of no social housing for immigrants - oh wait, already floated).

Rating Their Chances

At present Rishi Sunak must be feeling like most of his ‘fellow’ Southampton fans. Everything that could go wrong has gone wrong. The new blood in the team hasn't paid off. Years of carefully designed plans and policies gone to naught. People are even talking about bringing back the crazy manager who blew the team up and only lasted a few weeks Oh wait, no-one is talking about re-hiring Nathan Jones. Must be someone else…

No politician wants to go into an election with economic storm clouds overhead. Where politicians can time elections they tend to ‘surf’ good economic times. But time is running out for Sunak - he has to call the election before January 2025 - realistically in October 2024. As this weekend’s events in Russia show us, many things can happen in politics. I rule nothing in or out. But it’s a tough ask.

What I think this data does show, however, is that although the Conservatives won lots of constituencies where many people have a mortgage, they are far far more dependent on people who outright own their houses. And I don’t see how mortgage relief is in that group’s interests. They likely want tax cuts, or stopping new houses being built, or other retail positions that have been effective for the Conservatives over the years.

No, the problem of mortgage-holders is not Rishi Sunak’s. If the economy pulls a 180 he can win, probably regardless of whether he does something for mortgagees. The problem belongs to Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, both electorally and if they make it into office. Like someone getting a foreclosed property for a great price, they may discover that the economy they inherit is not all that desirable after all.

If you enjoyed today’s post, you’ll be delighted to know I have a new book out. Why Politics Fails was selected as an ‘unmissable’ politics book in Waterstones’ April monthly newsletter. So, don’t miss it! You can order from Waterstones here. Or a signed copy from Topping here. Or at the behemoth here.

And if you don’t subscribe - my Substack is free so please click below.

The possible collapse of Thames Water isn’t going to impress Wokingham voters either!

I live up the road in Reading and hear that the Lib Dem’s are campaigning very hard in Wokingham.

Brilliant analysis. Just for the record, mortgagees are lenders not borrowers.