Grasping for Growth

Labour claim to be 'single-minded' about economic growth. But do they have a theory of it?

Before we begin, a quick reminder that Radio 4’s Rethink, which I present, is back on air for the second run of seven shows for this season. We’re going to be rethinking museums, AI, heath data, and more. But first off, we’re rethinking political labels, with Claire Ainsley, Giles, Dilnot, Paula Surridge, and Sara Hobolt. This Thursday at 4 or anytime after here.

Pity the poor elected politician. One thing above all can keep them in office: ‘the economy, stupid”. And yet when they seek to push levers to affect this sine qua non of re-election, they often find that nothing happens, or that the whole lever comes off in their hands. They might suspect mournfully that they have been strapped into a childseat and given a toddler’s play steering wheel, while somebody else is driving the car. But you and I, on our family outing, do not then turn to the toddler and scream, ‘why did you do that?’ when we puncture a tyre and have to drive into a lay-by. No such reprieve for the politicians. The frustration of political impotence is real.

So it is not surprising that politicians try to exert some agency and to improve the economy through a range of policies: from fiscal to monetary to regulatory. At times, their efforts may be for naught, as every politicians seeking re-election in 2024 discovered. Sometimes there is very little politicians can do to effectively lower inflation, let alone return prices to where they began. In many developing countries, economic fortunes are largely set by international demand for primary exports - rubber, copper, coffee, oil. But, as the political scientists Daniela Campello and Cesar Zucco have shown, that doesn’t stop their electorates from blaming them for recessions (or indeed, rewarding them for booms they had little to do with).

Politicians in the UK are not in quite as disempowered a situation. The UK is still the world’s sixth largest economy. Sterling is an important-ish world currency. London remains one of the world’s great cities. And state capacity in the UK is high - if the government wants to change tax revenues or spending levels it can push and pull levers that do make things happen. Not economic activity necessarily but state activity at least.

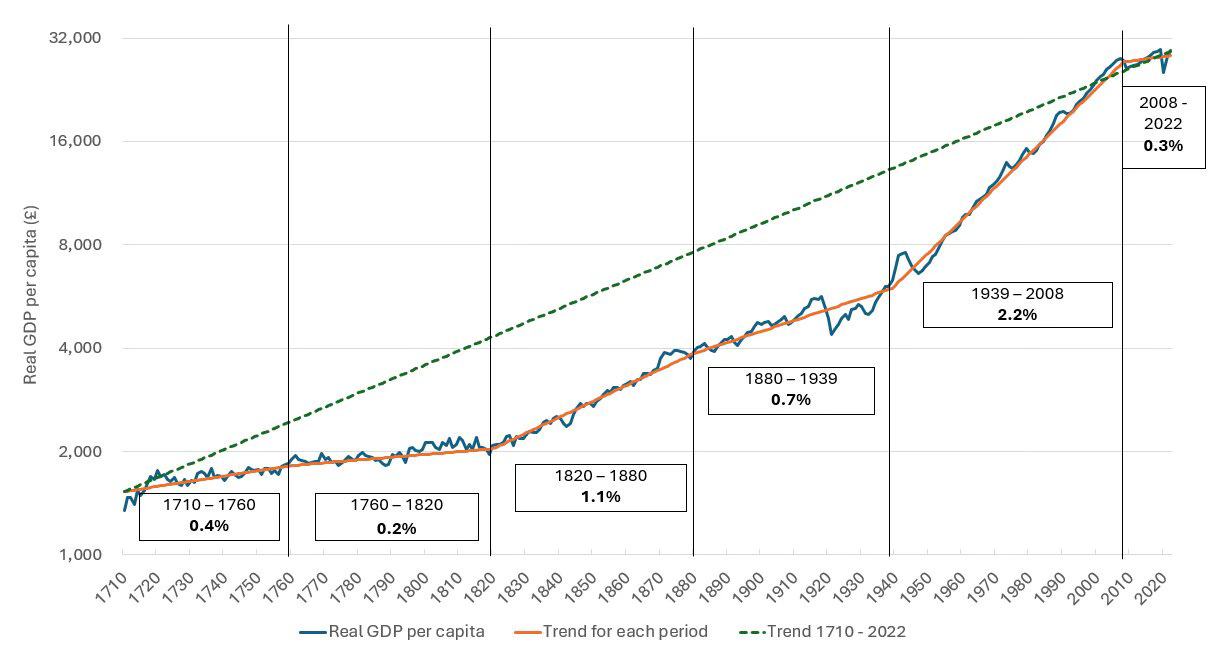

The problem is, however, that growth has been rubbish in recent years, as you can see from the graph above, created by Andrew Sissons using Bank of England data. We are back to Napoleonic era levels of growth. And getting Britain’s long-run economic growth onto a new trajectory? That is substantially more challenging. Not least because it is unlikely you can make that happen - and be seen to have happened - by the next election.

Still, over multiple election cycles governments can slowly change the ‘growth model’ of their country. In doing so, they need to be aware that some changes are more or less possible. The ‘growth models’ literature in political economy distinguishes between consumer demand-driven growth in the Anglo world versus export-led growth in Continental Europe. These are different equilibria that cannot just be switched back and forth - one does not simply walk into Munich.

However, within some parameters, canny politicians and bureaucrats can change incentives, channel resources, and sign deals that promote economic growth. But to do so, they need a mental model of how growth comes about. They need a ‘theory of growth’. This is not simply academic special pleading (well, only partly). Economic growth is an output. But what inputs produce it and how? There is a centuries long literature on what determines economic growth and as with most literatures it is riddled with disagreement on what matters most. And many, perhaps most, British governments subscribe to one or the other.

Labour’s Empty-Minded Pursuit of Growth

What is striking about the current Labour government is it’s not really clear what their ‘theory of growth’ actually is. Despite their claims to be pursuing it ‘single-mindedly’.

Keir Starmer’s grand AI strategy announcement this week - more on this later - was overshadowed by the Westminster Lobby playing their favourite game of “this is all a bit complicated and boring, can we please ask about who is up and who is down, thanks?” And the target of this week’s game was the Chancellor of the Exchequer herself, Rachel Reeves. Starmer failed to clear Lobby Management 101 by failing to declare that Reeves would be Chancellor until the next election (a No 10 spokesperson cleared this up later but too late). So now we have weeks of Reeves Deathwatch, including the Daily Star having cracked out their top lettuce Photoshop team.

Why is Reeves in peril? It’s not obvious that it is economic growth since Labour entered office in July last year that matters, though it has been essentially zero. It’s market expectations of future growth combined with a high interest rate environment that is mostly a consequence of Donald Trump’s re-election but is at least in part related to market views of Reeves’ budget and its likely impacts.

You will recall that Reeves raised taxes dramatically (though not quite at the level of say Norman Lamont in 1993), particularly through raising the national insurance that employers have to pay for staff members. There were also major spending increases for public services, including pay rises for frontline staff. It was, one must say, not an entirely unusual or surprising budget for a Labour Chancellor to give. But the rise in employer NI rather than one of the usual big three of income tax, personal NI, or VAT, has sent out unfortunate signals for Reeves. It has undermined her previous message that Labour would work more closely with business leaders than the previous Conservative Party whose ‘fuck business’ mantra under Boris Johnson had ruffled corporate feathers.

Fine, you might say, but Labour are a left-wing party - they shouldn’t be the party of business. They should be the party of workers and the users of public services. And it’s true that Reeves avoided raising taxes directly on workers - other than employer NI, the chief tax rises have been VAT on private schools and inheritance tax on farms. The problem is that neither of these are a major tax raiser and have the deleterious side-effect of rousing some of the nation’s most vigorous opponents - namely wealthy Southerners (witness the Lib Dems opposing VAT on private schools) and history’s most effective lobby-group - farmers. On top of which most people are rightly suspicious that there is no free lunch in taxation - employers NI rising will ultimately likely produce lower hiring or worse raises, not least because it was combined with a rise in the minimum wage.

Still, nothing hugely surprising from a Labour budget. The problem is that it has been combined with gloomy rhetoric since July, along with hints at a return to austerity, which means Labour voters would be forgiven for looking at all of this and saying, ‘is that it?’. But without economic growth it’s not clear that there really is much more than ‘that’.

Which leads us to the crux of the matter. Labour’s current plans on their own will not get them re-elected because there are minimal gains for most and tax rises, which even if disguised, are still likely to have contractionary effects. For the plans to work politically, they have to work economically, which means they need to create a framework for sustained economic growth by 2029.

But Labour does not seem to have a coherent theory of how that growth might emerge. Worse, the current agenda is a mishmash of different theories of growth that potentially offset one another.

So what do I mean by this? At the risk of losing my economics bona fides let me set out a crude guide to standard ways of thinking about economic growth and how previous governments have fit into them. I’m doing this rather in the spirit of this excellent piece about Labour’s public policy traditions by David Klemperer and Clom Murphy. Let’s start with the standard model: neoclassical growth.

Neoclassical Growth (Osbornism): This is where your standard economic growth textbook begins (I like Acemoglu’s and Aghion’s books but the first few chapters of Romer’s macroeconomics book are fine too). There are a couple of flavours of these models - either macro, like the famous Solow model, where we look at national-level aggregates, or micro, like the Ramsey / overlapping generations models. But the basic gist is that these are models where growth comes from having a higher ratio of capital stock to people, perhaps augmented by technology.

In this setup, there are a few ways to increase per capita growth. You could reduce population (the Black Death model of growth), you could increase the capital stock (i.e. the Industrial Revolution), or you could magic up technology (also the Industrial Revolution). Neoclassical models hold technology to be ‘exogenous’ (i.e. outside the scope of the model) so not much you can do there except hope that technological improvements fall like manna from heaven. Which leaves increasing the capital stock. And the way you do that is basically save more. A higher savings rate increases investment, which increases growth until you basically reach a new higher steady state. After that you are reliant on technology.

Growth in this model basically comes from creating a sound savings and investment environment. Things which scare off capital are bad. Things which attract it are good. Incentives to save are good. Taxing capital, savings, investments, etc are bad. Technology is great and you don’t want to harm it but it’s mostly outside your control as a government. And more generally, though this is dipping into macroeconomics more generally, inflation is a bad thing and should be crushed mercilessly. Public debt similarly is bad because you want to have resources channeled into private investment and financing, not to the state to subsidise ‘unproductive’ resources.

Again I am being crude here, but this is not far off the model that George Osborne adopted as Chancellor. Clearly Osborne was more directly focused on the deficit and debt in 2010 than he was future growth but in his view clearing the debt would reinforce the ‘right’ way to encourage growth. This is market-conforming growth policy, where your measure of success is “do the bond markets like it and will they lower the cost of borrowing accordingly”, encouraging more investment, and hence more growth (you hope). Oh and don’t go leaving a large single market in trade, capital, and labour.

Reeves’ existing policy regularly veers in this direction. Her own deficit and spending rules are market-conforming. Labour’s decision to rule out big ticket tax increases in the ‘big three’ and to avoid cranking up corporate taxation or capital gains taxes also come from this tradition.

Neokeynesian Growth (Brownish)

Now we move a little away from the standard models. First off, I have created a bit of a Frankenstein here because Neokeynesianism is a theory about how the macroeconomy works, focused on business cycle management rather than a theory of economic growth per se. But the types of growth theories that Neokeynesians, such as David Romer, have been attracted to tend to have a few things in common. In particular, that the image of a flexible, government-free market in neoclassical growth theory is neither accurate nor helpful in terms of setting policy.

Scholars in this tradition tend to emphasise, as Keynesians do, the role of aggregate demand. In particular, the possibility of a growth trap is prevalent in most Keynesian thinking (e.g. Paul Krugman) - if consumers are too poor or are too nervous about spending, they cannot provide the demand needed to encourage businesses to invest. Or, in a related fashion, the macroeconomy cannot adjust to market demand on its own because of price or labour market rigidities.

In the short to medium run this might mean the government needs to inject cash into the economy, through monetary or fiscal policy, ideally targeted at poorer citizens, in order to jump the economy out of its hole (an idea related to the famous ‘liquidity trap’). As a theory of long-run growth, though, this is not entirely helpful (it can’t really explain why countries grow faster than one another over a multi-decades cycle, unless they remain trapped in this low growth equilibrium indefinitely).

Which means Neokeynesians have tended to other long-run growth theories as their favourites. One was particularly beloved of Gordon Brown and his then advisor Ed Balls, who advocated in 1995, before Labour were in government, the tenets of “post neoclassical endogenous growth theory”. To which Michael Heseltine famously responded “That’s not Brown, it’s Balls”. Ho ho ho.

We would normally just refer to this as ‘simply’ endogenous growth theory (the post-neoclassical telling you that it is very much not our earlier theory). The big difference is that in this model, developed by Paul Romer (who won the economics Nobel for it), technological growth is not fixed but something that can be altered - hence it is endogenous. The crucial difference is that the parameter for technology in the model can be altered by active investments in human capital (aka education) or research and development.

So now governments have a mechanism beyond just encouraging savings to directly increase the rate of economic growth. In neoclassical growth theory, governments should get out of the way. In endogenous growth theory, they should target innovation, competition, open markets, education - anything that might improve the underlying rate of technological productivity. Governments now have an important role in growth. So you can see why this might be attractive to centre-left leaders. And it certainly was to Gordon Brown. It meant an emphasis on largely market-conforming policies but with investment in skills, universities, high-skilled immigration, and entrepreneurship tax breaks. And crucially, openness to Europe.

The other growth theory that centre-left leaders (and economists) tend to be drawn to is ‘institutionalist’ theories of growth. Most famously associated with the Nobelists Douglass North, Daron Acemoglu, Jim Robinson and Simon Johnson, these theories emphasise the importance of political and legal institutions in creating a framework for growth. Essentially these models take seriously political motivations by malign leaders to capture rents from the market themself - thereby reducing the incentive of private actors to invest and so forth. If you are an institutionalist, you take seriously the task of designing political institutions that create stability and punish corruption. Again there is a role for governments, though it might be more in the way of constitutional design than actively intervening. There are hints of this in New Labour’s institutional reforms - central bank independence, devolution, etc. And again you might shudder at the ideal of leaving a large multinational economic or legal institution…

Developmentalism (Labour Leftism)

We can push further, and now really outside mainstream economics, to a more interventionist growth theory, often associated with scholars such as Alice Amsden and Robert Wade. These theorists were inspired by the experience of the ‘East Asian Tigers’, particularly South Korea and Taiwan, in rapidly industrialising, albeit with much higher levels of state direction and intervention than prevail even in Europe. Scholars in this tradition draw on both economic historians such as Alexander Gerschenkron, who emphasised the ‘advantage’ of economic backwardness in permitting states to engage in ‘big push’ state-directed industrialisation, and arguably on theorists from a further left tradition, who saw in the industrial successes off the Soviet World a clear non-market strategy for growth.

Developmentalism is very popular among left-leaning academics but has been less influential in the Labour Party recently, especially when in government. But we can see it in Harold Wilson’s White Heat rhetoric and the importance of planning in both Attlee and Wilson’s governments. And I think we can see its legacy in Ed Miliband’s economic growth strategy (which was arguably about using some state intervention to push Britain to a more Germanic model of production) or Corbyn and McDonnell’s 2019 manifesto. In the current cabinet it survives in Ed Miliband’s Energy Security and Net Zero Department - the kind of place where developmentalism is going to make most sense.

This type of policy requires a robust state and potentially a certain distaste for constraining international rules - Corbyn’s pro-Brexit stance dovetailed well with a developmentalist view of the world. It arguably is going to be one of the most important themes of the next few years given that China is one of the models of developmentalism, Biden’s Green New Deal was developmentalist in nature, and Trump trade policy has a developmentalist tinge. Some versions of it also emphasise its protective capacity - shielding citizens from the vagaries of international markets. And here we can see some connections to the type of arguments that Rachel Reeves made in her Mais speech - the largely unpursued idea of ‘securonomics’. But that doesn’t necessarily mesh well with other current commitments…

Schumpeterian Growth (Cummingism)

Let’s now turn back to the right of the political spectrum. Most of the growth theories we have looked at have seemed rather benign in nature - we save more, or research more, or direct funds more, and we get growth. An alternative is to assume that economic growth is inherently destructive and messy. And then we enter the world of Schumpeterian growth models, which emphasise that economic growth comes from the famous ‘creative destruction’ of unproductive businesses, to be replaced by more productive ones. In other words, as technology develops, not every firm or individual can adopt it. So they are replaced by those that can. Schumpeterianism doesn’t have to be a right-wing view (Schumpeter himself had quite complicated politics) but for those who have a ‘red in tooth and claw’ vision of society and a lust for innovation, this is an attractive model.

And we quite recently had one such figure in Downing Street. Whatever else one might think of the Johnson/Cummings era, there was a quite clear economic vision, at least from Cummings. It was inspired by ‘rationalist’ thinking from the US West Coast and emphasised the importance of new technologies in generating wealth. It was destructive of existing firms and institutions that got in the way. But it was also genuinely transformative - creating new visas (the Global Talent visa) and agencies (ARPA) that might enact the vision. The problem it faced of course is that it was largely one man’s vision and its core era lasted only as long as he did. But when the government talks about artificial intelligence and entrepreneurship, even after the fall of the Conservatives, we can see the shadow of this more disruptive theory of growth.

Supply-Side Growth (Trussism)

And finally.

Here we enter a slightly less academically central theory of growth but one that has had huge political impact over the past half century, not least because of the famous Laffer curve, which implied that tax revenues could actually rise with tax cuts because high taxes lead people to withdraw their labour and capital en masse. For supply-siders, everything is about the incentives of people to work or invest. So there are clear connections to neoclassical growth theory on the more mainstream side of supply-sidism. But the basic gist is that economic growth would be persistently much higher under a regime of much lower taxation. In this manner it is essentially the opposite of more Keynesian approaches to growth - the government should not stimulate the economy or spend itself, it should be small enough to ‘drown in a bathtub’ (to quote Grover Norquist).

Tax cuts are the core of supply-sidism but there is a deregulatory bent to other areas that might promote growth. Supply-siders tend not to be hugely concerned about corporate concentration and are very leery of labour, product safety or environmental regulations that might reduce growth/protect people (choose your fighter). In recent years, they have become interested in homebuilding as a supply-side intervention that might promote growth in the UK - not asking the state to build these houses (god forbid!) but preventing local councils from blocking new development. Put together this was of course the Liz Truss agenda, blocked by a giant ‘anti-growth’ conspiracy of… well basically everyone at this point it seems, in her current telling. But while the program as a whole was a political failure, tax cuts, deregulation, and maybe building houses, are still very much on the agenda for many right-leaning politicians.

And Starmer and Reeves?

Not so clear. Despite the attempts by Reeves to set out her own securonomics agenda in the Mais lecture, it’s pretty hard to define a clear and coherent strategy. To paraphrase Walter Sobchak, say what you will about the tenets of Truss / Corbyn / Osborne but at least they had an ethos.

On the one hand we have a ‘don’t scare the horses’ form of Osbornism, where presumably we expect private investment to come save the day. Yet, it was business that was targeted with the national insurance hikes and the negative mood music from the PM and Chancellor appeared to hit confidence. And there is a continued refusal to countenance any substantial improvement in Britain’s relations with Europe - the government are leery about a youth mobility scheme (which they have with lots of non-EU countries already) let alone the single market. Osbornism without a market to sell into is pointless.

Then we have a set of more Brownist commitments to boost public spending and support people in the cost of living crisis. But at the same time, the growth sides of Brown have withered - universities have been largely ignored by the government, even as they teeter on the edge of financial collapse; skilled immigration is more likely to be cut than increase. And again the failure to re-engage with Europe in this area, including on Erasmus and youth mobility, weakens it as a potential strategy.

But maybe they really have a plan for growth without Europe. There is a dalliance with developmentalism - seen most clearly in the energy sector but also in the language around making the UK an AI superpower, free from the constraints of European regulation. But it’s very clear the Treasury’s heart is not in this - it has a longstanding hatred of ‘picking winners’. So that forces Number Ten to be the standard-bearer for developmentalism, which… um… it’s not.

On top of which there is some dalliance with growth theories more associated with the post-liberal right. The AI announcements from this week by Starmer have the scent of disruptive Cummingism and are hard to reconcile with the idea of securonomics. The announcements - but not yet policy - on regulatory changes to make home-building easier, have been applauded by (some) supply-siders, who otherwise have little to cheer.

So a little bit of this, a little bit of that. What’s the harm? Well, these approaches to growth are not obviously compatible. Securonomics might fit well with a neokeynesian approach that emphasised maintained public spending plus social investment, or with a developmentalist approach that was more protectionist - but it’s not clear these two models actually work with one another - for example, they fundamentally differ on relations with Europe - and that’s before we question how you are supposed to reconcile securonomics with a neoclassical, market-conforming approach to public finances, or with a disruptive approach to AI (or the civil service, per Starmer’s line from late last year about them being comfortable with the ‘tepid bath of managed decline’), or with a supply-side, rip-it-all-up approach to planning.

The thing about different theories of how the world works is that they are… well… different, often incommensurate. You can’t treat grand, clashing economic schools of thought like a jaunt through Woolworths pick and mix. You have to make a choice and direct the bulk of your policy in that direction. As I said last time out, to govern is to choose. Not just to do something (though that has been a problem) but also among distinct economic strategies.

Claiming pragmatism by borrowing bits here and there from incompatible ideologies will mean a Frankenstein’s monster of an economic strategy. And when the electorate come with their pitchforks and torches to ward off the monster, they won’t have much more sympathy for its creators.

But let’s not end on a downer. The parliamentary term is young - there is time to whittle down these theories of growth and choose to focus on a particular strategy. And Labour are far from the only government to have had a vague economic strategy - things were much worse, arguably, under Theresa May. What’s more you might just argue that consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds - and that my mind is especially little.

What Labour need is a few figures high-up with a crystalline sense of how to move forward and a deep understanding of the British economy and its options. People who can acknowledge but also look past immediate electoral concerns - that’s Morgan McSweeney’s job and he has done it well but it doesn’t follow that electoral needs solve economic problems. If only it were so.

And as luck would have it, just yesterday, the fall of Tulip Siddiq has meant the entry into the Treasury of a certain economist who ran the Resolution Foundation and has just written an excellent book on Britain’s woes and how to get past them. So good luck Torsten - I’d bring a few copies of the book to share if I were you.

Very interesting overview of growth theories. Prompted me to think what Labour has said about how it plans to promote growth. Off the top of my head I can recall the following:

1. Stability, after years of political and economic policy chaos. I think this is necessary (having worked for years in an industry with long term investment horizons I think the importance is under-rated) but is mostly table stakes.

2. Planning reform. This could be very important - I read somewhere that every extra 100,000 houses built adds 0.8% to GDP (which would mean a value add of about £200k per property, which seems plausible). And of course local authorities in some parts of the country and (often ineffective) environmental regulations have led to several major investments being refused (from film studios to data centres). We have almost certainly been losing many £billions of investment a year because it is so hard and expensive to build.

3. Related to that is infrastructure investment, which they have talked a good game on but their plans are still quite vague (eg HS2).

4. Improved trade relations with Europe, but so far only proposals for tinkering on things like food standards that will only have a marginal effect, but perhaps will benefit specific fishing and farming communities a lot.

5. A renewed focus on industrial policy (AI, green technologies, creative, National Wealth Fund etc). This could be useful but will inevitably be a bit marginal.

I think they are all directionally right, but it is early days and they need to go further in many areas. I’m also note sure that they all need to align to one growth model as none of the above are mutually exclusive.

There’s also been no mention of tax reform that I’ve seen, and that is probably useful too given that thinks like VAT thresholds, differential treatment of self-employment and investment income to employee wages, and property taxation all have negative distortionary growth effects.

Having said that, we are only sixth months in to a 4-5 year parliament and it is possible that lots of things are being developed within government at the moment.

Excellent piece!

(Btw, I think there's a slight typo (off/of) in the paragraph on Soviet Union economic development)