FADFO

A lot of people have a 'need for chaos', as long as there's no chaos

When, in decades to come, history students look back at the late 2010s and early 2020s - assuming there is still a world left where people can study history - they will as one ask a confused question: “Why was there a Leopards Eating People’s Faces Party?”

Our future historians will have to remind their charges that this was an ironic phrase - a party name given as an insult by opponents - like the ‘Know Nothings’ or the ‘Levellers’. Whether a brave party out there will do as those predecessors did and adopt the insult as their name remains to be seen.

But our apocryphal Leopards Eating Faces Party joins a series of other contemporary memes expressing a related point - Hot Dog suit guy, Withnail and “I” having gone on holiday ‘by mistake', cartoon blob guy having smashed up his room because he wanted things to be different.

And most recently, the Fuck Around Find Out Econ 101 lecture. For those who haven’t seen this particular video - see below. The gist is a bespectacled middle aged lecturer giving an Econ 101 style tutorial about the positive and linear relationship between ‘fucking around’ and ‘finding out’.

All of these memes have the same thing in common. They allow people on social media to tut and moan about the obvious stupidity of other people…

OK, they do a bit more than that. They criticise populists for having voted for populist parties and then discovering, after the fact, that they might in fact be hurt by the policies or rhetoric of said populists.

Is this a fair critique? After all, we could make of it anyone who votes for a party that gets into office (not a problem I face in the near-future, living in a Lib Dem/Conservative marginal). There’s nothing stopping Kemi’s army of young very-online Conservatives from posting hot dog guy or leopards eating faces memes about Labour voters. But it does seem these memes have a particular target - people who vote to smash up the system and then complain about the consequences of a smashed system.

What I want to do today is to defend these people. That should make this a popular post… Now, I don’t want to defend all their worst instincts. Some people do vote for populists to maliciously punish other citizens or, especially, immigrants. That there is collateral damage that then hurts them is not entirely unsatisfying to many of us.

But people who want a change? Who think the political and economic system is broken? Who think it’s all a stitch-up? Those are understandable preferences and beliefs. Voting for change and then having the change agent fail to bring it about is not a personal failing. It’s a failure of the politician making unfulfillable promises.

This is where I think wannabe disruptors from Dominic Cummings to Morgan McSweeney have a point. If there is a generalised mood of discontent in the country it’s not anti-democratic to want a bit of disruption to shake things up. For more, see my lengthy excursus a few weeks ago on disruption.

However, there’s another group of people, though, about whom we might have a slightly different take - people whose lives are easy and vote for disruptive populism on the assumption it won’t change anything about their lives.

These people believe in FADFO - Fuck Around, Don’t Find Out.

And while I might have some moral qualms about this kind of Daisy and Tom Buchanan style attitude, in a way I can’t totally blame these people. For the past couple of decades, FADFO has been pretty accurate. The question is whether that’s still true. Are we, keeping with my new coinage, moving from FADFO to FAFO?

Chaos Chasers

The first thing we need to clear up is why would people want to Fuck Around in the first place? And what does that even mean?

Basically, I take it to be the desire that people have to upend the existing system. That might mean a deliberate strategy of disruption with an endpoint in mind - à la Cummings/McSweeney. Or it could be a somewhat more inchoate and wide-ranging disruption which has a general direction - smaller government - but doesn’t really care how it gets there - à la Milei or Musk. Or it could just be a pure taste for disruption. Whatever, whenever, however.

Psychologists refer to this last manifestation as a ‘need for chaos’. This is a personal characteristic. A desire for the process to be disruptive without any end point in mind. The means justify the ends. And the means are madness.

There’s an element here of Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now. When Captain Willard finally locates him deep into the jungle, Kurtz asks him ‘are my methods unsound?’, to which Willard replies ‘I don’t see any method at all, sir’. The chaos is the point.

There are some people for whom the ‘need for chaos’ is a deep psychological disposition - not a majority of people by any means, perhaps not even a majority of people who vote for populists. But an important and maybe growing group.

The best analysis of how such people think about the world comes from a recent paper in the American Political Science Review by Michael Bang Petersen, Mathias Osmundsen and Kevin Arceneaux. Their paper is interested in the connection between the alleged ‘need for chaos’ and the ‘motivation to share hostile political rumors’. The authors develop an index that combines answers to questions such as the following:

I fantasize about a natural disaster wiping out most of humanity such that a small group of people can start all over.

I think society should be burned to the ground.

We cannot fix the problems in our social institutions, we need to tear them down and start over.

Sometimes I just feel like destroying beautiful things.

I think it’s fairly apparent that these questions do indeed tap into a ‘need for chaos’.

You will probably be relieved to know that there is not a majority out there for burning society to the ground. Nonetheless, when the authors normalise their index to be between zero and one, the mean response is about 0.2 and there is a long of thin tail of chaos-needers with high scores.

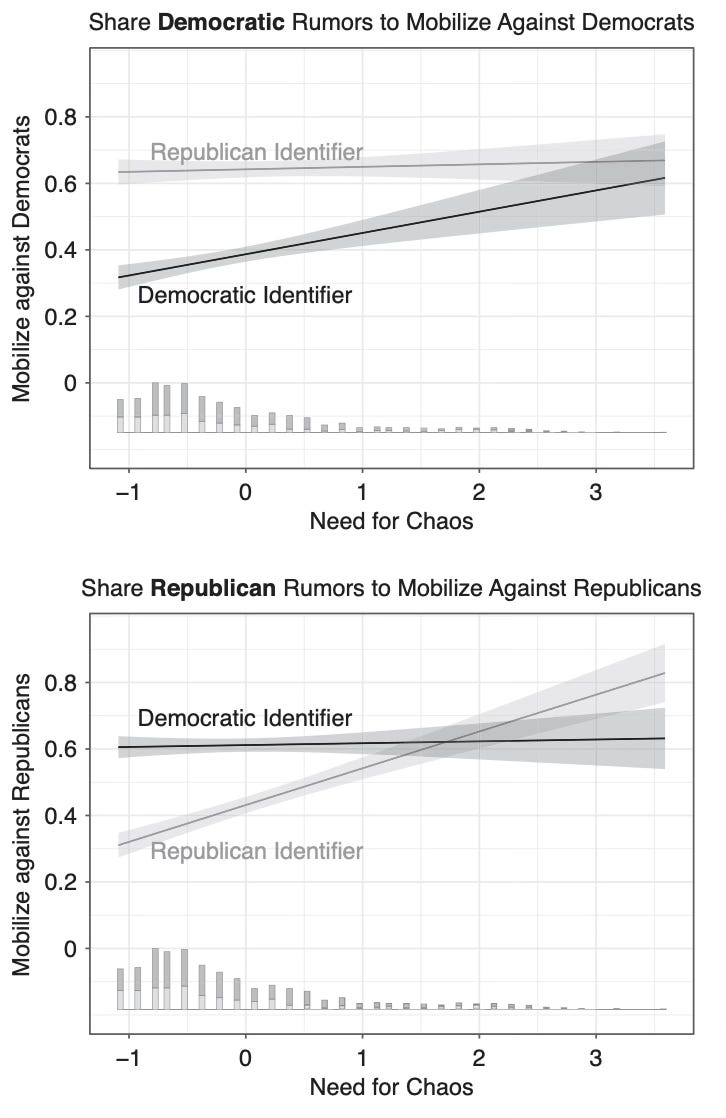

The authors then experimentally test the reaction of survey participants to various untrue rumours. Their studies are all on Americans, and were fielded between 2018 and 2022. They have some untrue rumours about Democrats: “Former President Obama has been creating a‘shadow-government’ to take down President Trump”; and some about Republicans: “Republican Tax Bill Passed in December Stops Medicare from Covering Cancer Treatment.”

Unsurprisingly, people with a need for chaos are more likely to believe such rumours and are also more likely to express the intention to share them. What is perhaps more surprising is that this pattern is almost identical across Democratic and Republican voters.

There’s an interesting explanation for this - Petersen et al asked people about their motives for sharing rumours. The most obvious one is to hurt the particular party that the rumour is about. And among people with low need for chaos, you see the obvious partisan effect - Republicans like sharing the anti-Democrat rumour in order to hurt the Democrats and vice versa. But among people with a very high need for chaos? They are happy to hurt both parties - including the ones they support! You can see this in the figures below, taken from their paper. So this isn’t just negative partisanship - it’s a more deeper craving to destroy both main parties. And this is not a Republican-only phenomenon, there are chaos-needers in both parties.

Who needs chaos? Basically people who feel low status in some way: those who place themselves low on a subjective ‘social ladder’ or who feel isolated. This seems to be about personal social status, especially about a fear of losing it, rather than group social status. This connection between status and need for chaos is most pronounced among white men. However, lest you think this is the standard story about white men in America versus other groups - the two groups with the highest average scores on ‘need for chaos’ or black women and black men. So again, this isn’t just a story about white Republican voters voting for Trump - the ‘need for chaos’ is a much more pervasive phenomenon.

So that’s one story about who wants to fuck around. It’s those who feel left out by society in some way, whether it matches to their material circumstances or not. It’s about respect and status - or rather the lack of both. This is consistent with all kinds of stories about being ‘left behind’ or ignored by elites and isn’t just limited to white rural voters but a whole swathe of disaffected Americans. Indeed, it might help explain the relative success that Donald Trump has had among minority voters, since the need for chaos is a pan-racial attribute.

What is not so clear to me is how these people would feel if they actually ‘found out’. If status hierarchies were reversed - or more pertinently if the much feared change in relative status hierarchies was reversed - then maybe they really would be happy with the consequences of chaos. But equally, actual chaos might just beget the desire for even more chaos, should it not produce the desired results. Disaffection doesn’t easily produce affection.

However, it will not have escaped your attention that there seems to be a larger group than just the perennially disaffected who are interested in voting for disruption. Indeed, the stereotype many have of the archetypal Brexit voter is a well-to-do retiree putting the world to rights in a leafy Kent pub garden (without wishing to disclose too much about my own upbringing…). These people don’t exactly scream chaos. They are comfortable, conservative and generally rather disapproving of change.

Or at least change that might affect them. Wealthy people are shielded against the material consequences of disruption, especially retired wealthy people. So another group of pro-disruption voters are not attracted to disruption for its own sake but simply aren’t worried about its consequences. They can pull the electoral lever whichever way they want and life will go on regardless.

My colleagues Jane Green and Raluca Pahontu have an important recent article about this group and their vote during Brexit. It’s an excellent piece not least since it pushes back against an argument that David Adler and I made in an earlier article. David and I had claimed that the geographical pattern of voting for Brexit was such that places with cheap housing voted to Leave and places with expensive housing voted for Remain - and that this was true not just in the country as a whole but at much lower levels of aggregation - e.g. looking at electoral wards within just the City of Bristol. So if you believe us, wealthier people wanted the stability of Remain, the left behind the change (chaos?) of Leave. You can see that geographical pattern below.

But Jane and Raluca argue that this isn’t the full story - the core Leave base are actually the wealthier voters in these less wealthy areas. So there is an ‘ecological inference’ problem in my piece with David. They find this across several surveys, including with panel data (i.e. not just the cross-sectional difference between people with different wealth but also the dynamic difference among those whose personal wealth changes over the survey) and with an experiment that prompts people to think about receiving a windfall. In all cases, personal wealth makes people feel more positively about voting Brexit (before the referendum) or about whether it was the right choice (afterwards).

Why? Jane and Raluca argue that wealth acts as a buffer against risk (they kindly cite an earlier paper I wrote on this topic). They show that personal wealth accordingly reduces people’s risk aversion - it makes them more tolerant of taking large political risks. So it could be that lots of people liked the idea of Brexit but only those with substantial wealth felt comfortable acting on that preference - Jane and Raluca certainly find some support for that claim. Or it could also be that feeling insulated from bad outcomes just makes people more attracted to risk-seeking behaviours, such as ending a decades long set of international commitments. Whatever the reasoning, we are now all in the joyous experience of ‘finding out’. It’s just that some people are ‘finding out’ more than others, whose jobs or wealth are less connected to major economic shocks.

So we have a couple of potential motivations for Fucking Around - a psychological one and a material one. If you combine them you move from a minority of voters to a plurality, perhaps majority. An odd coalition of the disaffected and the blessed.

But before we move on to the consequences of these attitudes I want to suggest a couple of other forces that might amplify them. The first is the rise of ‘political hobbyism’. I wrote a long piece about this last year so I won’t recapitulate it but briefly the idea comes from the American political scientist Eitan Hersh, who argues that there is a growing group of people who engage in politics for ‘consumption reasons’. That is, they don’t really care about the outcomes of policy per se, they just like to debate, take sides, get in online fights etc. It’s easy to see how hobbyism might be especially attractive to those who want to blow things up or who have lots of time on their hands and a nice warm drawing room in which to go ballistic on their laptop.

The other force is the all-pervading temptation for contrarianism in online media. When people no longer buy the whole newspaper but instead click through to individual articles, your incentive as a publisher is to drive outrage or shock and one easy way to do this is to constantly argue that the mainstream is wrong and to hint that conspiracies might be right. And that we should be sneering at so-called ‘normies’ who like the way things are.

A quick perusal of right-leaning websites such as The Critic, Unherd or Quillette shows how successful that strategy has been but it has also been adopted by nominally centre-left periodicals such as the New Statesman and by once-fusty, quasi-reactionary but now contrarian-brained newspapers such as the Daily Telegraph. Writing a contrarian piece that argues for blowing everything up gets you clicks and, well, you’re not really responsible for the consequences. And there probably won’t be any, right? Right?

The Era of FADFO

For a long time that indeed seemed about right. You could Fuck Around, you Didn’t Find Out.

We were in the upper right quadrant of the well-used Anakin-Padme meme below. Which rather raises the question of why didn’t we Find Out?

Anyone familiar with the Millennium Bug story will have an inkling. There were great concerns in the late 1990s that the IT architecture on which modern prosperity depends was about to collapse at the turn of the century because computers had not been set up for 99 to become 00. And then when midnight struck not much happened. Quite similar really to my experience on the banks of the Thames, having exited some hipster club in Shoreditch to go and see Bob Geldof’s promised ‘river of fire’. Reader, the river was not ablaze. But good news, nor were the IT systems of every major corporation.

This then led to lots of ‘ho ho ho the Millennium bug was never real’ chat. But it was real (I know, my Dad worked on HSBC’s response to it). It’s just that people had fended it off so we never saw it. It was the dog that didn’t bark - the absence of something told us that something else important had happened - legions of IT consultants had forestalled the crisis from ever happening. Similar stories can be told about the ozone layer, various foiled terrorist attacks or avoided pandemics.

That humans are good at preventing problems from happening means that people can happily vote to create chaos, knowing that someone else might actually step in to prevent it from really happening. So you can have your expressive chaotic vote without the sickly aftertaste of chaos actually happening.

By and large this is a decent explanation for Trump 1.0. Trump’s initial cabinet and White House staff had lots of establishment Republicans - titans of industry, well-known bankers, long-serving governors or party insiders. There are countless stories of these figures talking Trump off the edge from his wackier plans, changing the subject, or slow-walking his policies. The chaos was caged. And voters could ‘enjoy’ the chaotic rhetoric of Donald Trump without the actual chaotic reality.

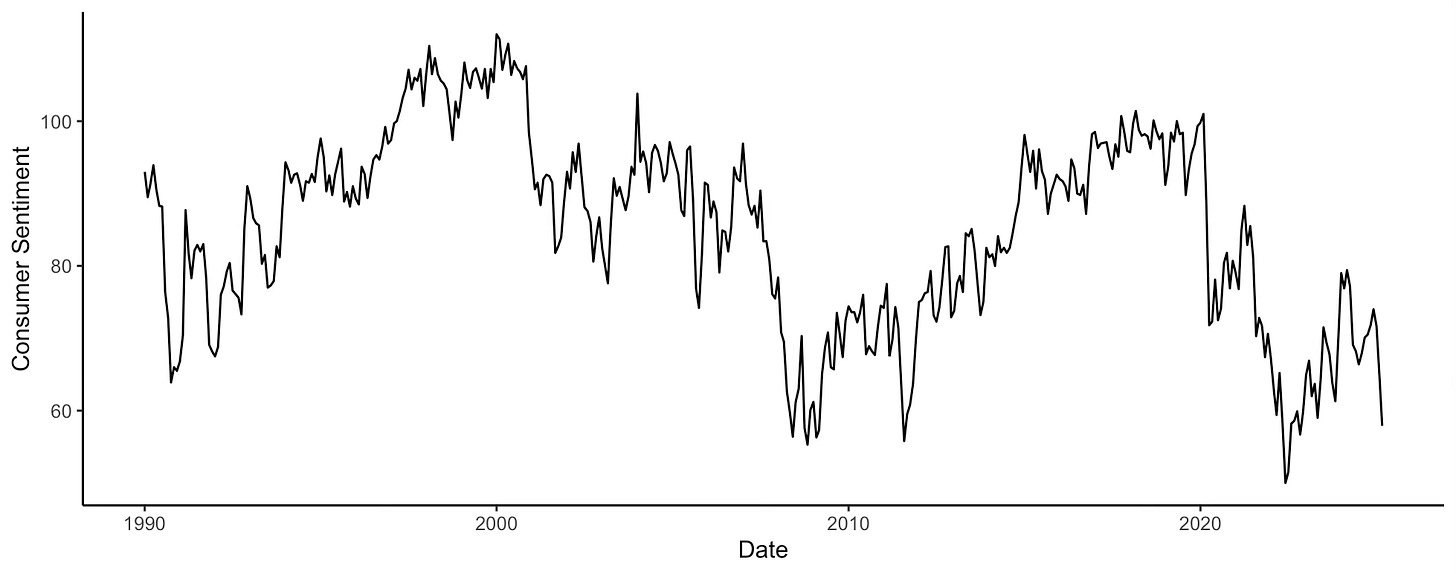

I say this not to intentionally demean or downplay the litany of missteps through episodes of active cruelty in Trump 1.0 - from separating children from their parents at the border through pretending the pandemic wasn’t happening for several weeks. But for the average American a lot of this passed them by. And until COVID, the American economy did very well - here is a graph of average consumer sentiment which I made using the Michigan Consumer Sentiments Survey.

Ah, the late 1990s - return my golden youth… But also the period from 2015 to 2020 looks very strong in terms of consumer sentiment. This is what Trump voters in 2024 presumably wanted to RETVRN to. The pandemic clearly smashed that but even worse was the inflation following COVID and especially the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Consumer sentiment in 2022 was worse than in the Great Recession. Although, you know what also looks like the Great Recession? The last measure in the graph (March 2025). But we will come back to that.

We Brits also had our own experience of FADFO. One truism about Brexit is that it was (indeed still is) a process, not an event. The referendum occurred in 2016 but Brexit proper did not begin until 2021 (Britain left the EU officially on Jan 1st 2021 and the Trade and Cooperation Act began in May that year). Indeed, arguably we still haven’t properly Brexited - not in the way that Brexit diehards understand that phrase - but in the sense that the UK still has not adopted it’s full promised set of import controls (e.g. on fruit and veg). That means that for almost a decade after the Brexit vote the full implications had not been brought to bear and it took almost five years for the actual act of Brexit itself to occur.

As actual Brexit has slowly occurred it has become ever less popular. In January this year YouGov found that just 30% of the population thought it had been the right idea in retrospect, their lowest number on record. So we have had plenty of time to repent at leisure. But the gap between FA and FO was extremely long. Indeed, by the parallel I drew a year or so back between Brexit and Prohibition, we are now only seven or eight years away from its end… BTW, modesty aside, that’s one of my favourite pieces I’ve done here, so you know what to do.

FADFOing is not just a populist pursuit, although it is definitely a cakeist philosophy. I think one could argue that upper-income liberals have been happily FADFOing since the 1990s. The well known shift of high education / (sometimes) high income people towards centre-left parties depends not a little on the belief that although these parties claim to want higher taxes and redistribution they won’t actually go through with it. I don’t like the term ‘virtue-signalling’ much but one could claim that upper income liberals have had the best of both worlds - being able to vote for allegedly redistributivist parties without actually risking the redistribution. “Tax me more” I say, while knowing I won’t be taxed more…

Or we could look at Defund the Police as another FADFO policy. I believe there are indeed a number of true believers who really think the police should be either scrapped or massively deprived of financial resources. But I think there were quite a few fellow travellers who were justifiably angry about police brutality but who also quite like the police being able to protect their property, warn off vandals and shoplifters, etc.

My old stomping grounds of Uptown in Minneapolis experienced this back and forth after the killing of George Floyd a few miles away down Lake Street. There were lots of protests against the Minneapolis Police (who absolutely had previous) and Minneapolis promised to reform the police and constrain it. Unfortunately this precipitated many police officers leaving the force and a rise in crime in Minneapolis. Nobody was happy. And once the FADFOing became FAFO, support for Defund the Police collapsed.

From FADFO to FAFO

So what happens when you Find Out?

Well, it appears we are on the cusp of finding out about Finding Out. There have been a litany of hot-dog car man style quotes from various US business leaders and titans of Wall Street. Just a few months ago, post the Presidential Election, the types of quotes reporters got from finance guys were along the lines of “I’m so glad that I can feel free to say slurs again without being cancelled”. To which one might say, oh… that’s nice for you.

It turns out that Trump 2.0 does not mean only freedom for slurs. Along with the vanquishing of ‘woke’ there appear to have been several other victims so far, including free trade, support for Ukraine over Russia, USAID, the Department of Education, the National Institute of Health, Venezuelans with Real Madrid tattoos, French scientists who text their friends that they don’t like Trump’s science policy, and the potential sovereignty of Canada.

I will remind you that we are just two months in.

I am sure that there are millions of Americans absolutely loving this. They voted for Trump to own the libs. And the libs are being owned.

Along with America’s reputation for stable legal governance, scientific supremacy, safe tourism, military leadership, peaceful relations with its immediate neighbours, and having musicals that aren’t Cats being produced at the Kennedy Center.

The Wall Street Journal has lost patience - calling Trump’s tariffs the ‘dumbest trade war in history’ and receiving various not-so-veiled legal threats from Trump’s social media accounts. The Financial Times has interviewed market-markers who have belatedly realised that there is in fact no ‘Trump put’ that will make them money.

Remember the end of the graph I posted earlier - that was consumer confidence collapsing during February and March according to the Michigan Consumer Sentiment Report. Markets have been expecting higher inflation and slower growth - and the Fed came out and said just that this week. This led to a short-lived boom in the stock market because maybe the slower growth part means lower interest rates for longer. Eeesh. It feels like Trump’s plan is to get higher economic growth in the long run through forcing lower interest rates in the medium run by harming growth in the short run. This is indeed very stable genius.

So what will the public think if indeed they do have to Find Out? Well the jury is out for now but Trump recently scored his worst ever approval ratings on the economy. He already has 56% disapproval on the economy, having never hit 50% before. I know Chuck Schumer is public enemy number one among Democrats right now but there is a ruthless logic to his ‘don’t just do something, stand there’ strategy - Trump is doing a great job himself harming the economy and the public will Find Out.

But will they? I remain hopeful that America’s (federal) electoral system will remain largely protected against the vicissitudes of Trumpism. But just because people are unhappy does not mean they will always reward the mainstream opposition. And if they do, it might be brief, as Sir Keir Starmer knows only too well.

And here’s the thing about FADFO politics - if you have a need for chaos, well, congrats you got it! And if you are financially insulated then maybe you can still buy eggs. If you’re a hobbyist, maybe you’re into FADFOing for the love of the game. And if you’re a contrarian, you still need someone to pay you for those high click-through pieces. We have become addicted to FADFO. It has a large support base. A little bit of FAFOing doesn’t mean the doom of FADFO.

And while the political thermostat may well kick in as we Find Out, there is a more worrying alternative. This week I attended an IPPR event with the - dare I say contrarian - title of “Autocracy or bureaucracy - what is the real threat to democracy in 2025?” I got to follow John Redwood, Polly Toynbee and Polly Mackenzie, which I suspect was like having dry crackers for dessert for the audience. Not least because I cracked out a book on democracy from 1992, with a chapter from the storied Harvard historian Charles Maier. And I read out a quote, about politics at the turn of the twentieth century:

In the last analysis, so the new rightist critics maintained, democracy failed because it was a regime of useless discussion and insufficient action […] If no compromise were possible, discussion was misplaced; action by audacious minorities was crucial. The turn of the century brought a longing for such decisive minority currents to offset the languor and indolence of democracy. Male action - whether conquering African wastes, competing at the Olympic Games revived in 1896, making cavalry charges in Third World wars, planning revolution - returned to fashion after a generation of pacifism. The quest for élan vital pervaded philosophy and glimmered as a personal orientation.

p.139, Charles S. Maier ‘Democracy Since the French Revolution’ in John Dunn Democracy: The Unfinished Journey. OUP 1992.

What happens when populists fail? When you Fuck Around and people finally Find Out? I’m sure many liberals would like to believe that the electorate will sheepishly line up at the polls to vote the mainstream back in. I recall a certain someone making a similar point in a recent post about ‘peak populism’.

But there is an alternative - that people get fed up with the ‘useless discussion and insufficient action’ of democracy. There’s a lot of talk about ‘chainsaws’ in the Labour Party at the moment, which suggests Morgan McSweeney at least is concerned about this. Perhaps rightly.

Liberals should not be confident that floundering populists guarantee their own revival. If people have Fucked Around and then Found Out, it won’t do to superciliously say ‘I told you so’ and expect them to feel ashamed. No-one likes to feel like that, for understandable reasons. And we should not blame people for trusting politicians to come through on their promises.

And, most importantly, if people are pushed into shame they might look for succour elsewhere - outside of the democratic offer. Because the electoral thermostat could in fact be broken. And when a democracy that promised FADFO gives you FAFO, people might not ‘come to their senses’ and do what their ‘betters’ tell them. They might instead desire a bit of élan vital in the hands of an ‘audacious minority’.

This is fascinating and I think it applies strongly in the activist space as well. The term I've always used for it is 'escalators' - people or organisations who, given a crisis, will always try to increase the complexity or drama involved instead of breaking it down and working towards a solution. So with e.g. climate activism, you can see this in protest groups who wrap the whole thing up with ending capitalism, Gaza, minority rights and god knows what else, until there's this massive intractable knot of stuff that precludes any notion of actually fixing it.

It's almost like they *want* a gigantic omnicrisis because that's more exciting than just boring climate change. So they go and scream at people on the M25 and it feels like that's... sort of the point, to go out and do chaotic, shouty, cathartic stuff without any risk that you might have to actually take responsibility for a real problem or fix it.

And inevitably the kinds of activists doing this are often time-rich, public-school types who are relatively insulated from the consequences, which is why I think the Just Stop Oil jail sentences were quite triggering for some of these groups - they were essentially privileged middle class people who were shocked that doing something illegal and disruptive might actually result in serious consequences for themselves. There's a sense of "yes but surely prison isn't for real people like me?"

I loved this because FADFO essentially 'recodes' the concept of 'luxury beliefs' in a way that has resonance for a left-wing audience (and, helpfully for those of us on the right, is a useful reminder that luxury beliefs are not necessarily the preserve of the left - I think you're on the money on the 'protected from consequences of chaos' point).

As someone who thinks luxury beliefs are real, and a problem, I will be referencing this post next time someone tells me they are a 'far right myth'.