Democracy, Alive and Creaking

2024 was supposed to be the year where 'democracy will fall off a cliff'. Did it?

2024 was the supposed ‘year of elections’. I wrote a summary of how the year went, riffing off Frank Fukuyama’s famous original End of History essay, for NPR. You can read it here. Or hear me talk about how the year went with my regular sparring partner, Adam Fleming, on BBC Newscast (on audio here for 17 mins in or on Youtube here). For many people, this was a moment of truth.

The Nobel Peace Prize winner, and founder of the Filipino news website Rappler, Maria Ressa argued back in 2022 that “Unless something drastic changes, 2024 will be the year where democracy falls off the cliff.” Well, we are into the final ticks of the annual clock. Was this hyperbole? Or did democracy actually fall off a cliff after all?

I prefer to think of democracy as Wile E Coyote, having dashed several yards off the cliff face and now pumping its legs frantically to stay afloat. The doomed crash has not happened. Not yet. The signs are there of weaknesses in the democratic foundations. But for now, things look much the same, save with the spectacle of no ground below.

Now in the Warner Brothers tradition, Wile E Coyote will inevitably plunge to his (temporary) doom into the canyon after his leg spinning has come to an end. But let us suspend our disbelief, like good cartoon-viewers, and extend some, presumably ACME-made, bridge out to support our canine protagonist. Maybe democracy can edge back onto safer territory again. There has been no plunge, as yet.

In fact, at the margin, I suspect that the people who measure democracy at places such as V-DEM, Freedom House, and so forth, will see very little change in their measures for average democracy worldwide in 2024.

Anyway, to the ‘year of elections’. Half of the world’s population live in countries with major elections in 2024 and half of those people could actually vote in ‘free and fair’ elections. Billions upon billions voting. But not always meaningfully. Elections are everywhere. Competitive elections not so much.

That suggests that global democracy shouldn't be confused with global elections. And further that, ‘liberal democracy’ - combining free and fair elections with speech rights, protections for minorities, checks and balances against executive overreach - shouldn’t be mistaken for simpler ‘electoral democracy’ where you have the fair elections but not necessarily much else.

If we are talking about 2024 being the year democracy could ‘fall off a cliff’, well we would have to see some serious changes in either of these too metrics - liberal democracy or electoral democracy - and those would need to be pretty major institutional changes, not simply angry or populist rhetoric by the people who happened to win elections.

V-DEM haven’t yet updated their indices - we will need to wait until March probably for their next release of their Annual Democracy Report (here’s last year’s). But as I mentioned, I suspect there won’t be huge changes, and certainly not massive negative ones. Briefly, there have been positive signs in Bangladesh (the fall of Sheik Hosina) and Syria (the fall of Assad to be replaced by ???) and negative ones in Venezuela (another faked electoral victory for Maduro), and Russia (ever-growing crackdowns and another Putin mega-victory). But most of the interesting elections of the year have been about the failure or success of strong-men (or -women) leaders in countries with relatively free elections.

For the first half of the year, you could have told a story about weak strongmen - Tayip Erdogan losing control of several major Turkish cities, Narendra Modi not only failing to reach 400 seats in the Lok Sabha but actually losing support and his outright majority. By the late summer you had a mixed story - populist parties doing well in the European elections, and in vote share terms in the UK, but weaker than expected in Macron’s unexpected French parliamentary elections. And then we had the end of the year: Austria, Georgia, Romania, and of course America.

It’s those final elections that have soured the year of elections for those who worry about populism, those who see it as foretelling the collapse of democracy. But the story seems less clear to me. In the Austrian and American cases, these were free and fair elections, and the populist party won fair and square. Donald Trump may not be an obvious fan of liberal democracy, but he has certainly won on its terms. Those people who want to claim shenanigans about the US election have to lean very heavily on arguments about the media not covering Trump properly, being unfairly harsh on the Biden economy. Perhaps so. But that does not mean an illegitimate election nor any obvious weakening of democracy.

The elections that worry me more were those in Eastern Europe, not least because that is where I imagine in 2025 democracy could actually fall of a cliff. In Georgia, we saw very heavy Russian influence supercharge Georgian Dream’s victory in their recent elections (where there were quite credible claims of shenanigans at the voting booths). Russia was less successful - but only just - at influencing the Moldovan election. And most recently, the Romanian Presidential election was actually annulled because of the rise out of nowhere of the pro-’peace’/anti-Ukraine candidate Calin Georgescu on the back of a possibly Russian-inspired TikTok wave. Cancelling elections is a very much non-ideal outcome in a democracy. And so the question has to be, was that better than the alternative of suspected malign foreign influence?

All of these cases have, of course, in common the heavy hand of a large autocratic power sitting close by and attempting to secure parties and presidents sympathetic to its agenda by direct electoral interference. It is not always formal changes that matter - though the Georgian ‘Russia bill’ against (other) foreign influence would likely be coded as a formal decline in liberal democracy in Georgia. The informal influence of authoritarian countries is much harder for analysts of democracy to categorise, code, and understand. Or sometimes to separate out from ‘benign’ pro-democracy influence of Western NGOs or governments. But if democracy does fall off a cliff in Eastern Europe over the next few years it will be because it was pushed…

Still, I don’t think we should be in a panic and pronouncing the global end of democracy on the basis of the last year, or indeed the last decade. Not least because there is a danger of ‘boy who cried wolf’ reactions among those less worried - it’s pretty clear, for example, that the Democrats claiming ‘democracy is on the ballot’ was disbelieved by enough swing voters to be essentially ineffective, perhaps even counterproductive.

Taking a long view, while democracy is certainly not resurgent right now, arguably the claims of global democratic backsliding have been overplayed. Indeed, according to Andrew Little and Anne Meng, political scientists have been exaggerating the level of backsliding by focusing on subjective expert evaluations rather than more ‘objective’ indicators.

But even if we use the standard more subjective indices - in particular, those produced by the V-DEM institute, which combine expert evaluations in a measurement model that shows the degree of uncertainty among experts - it’s still not clear that in 2024 we were on any kind of precipice at all.

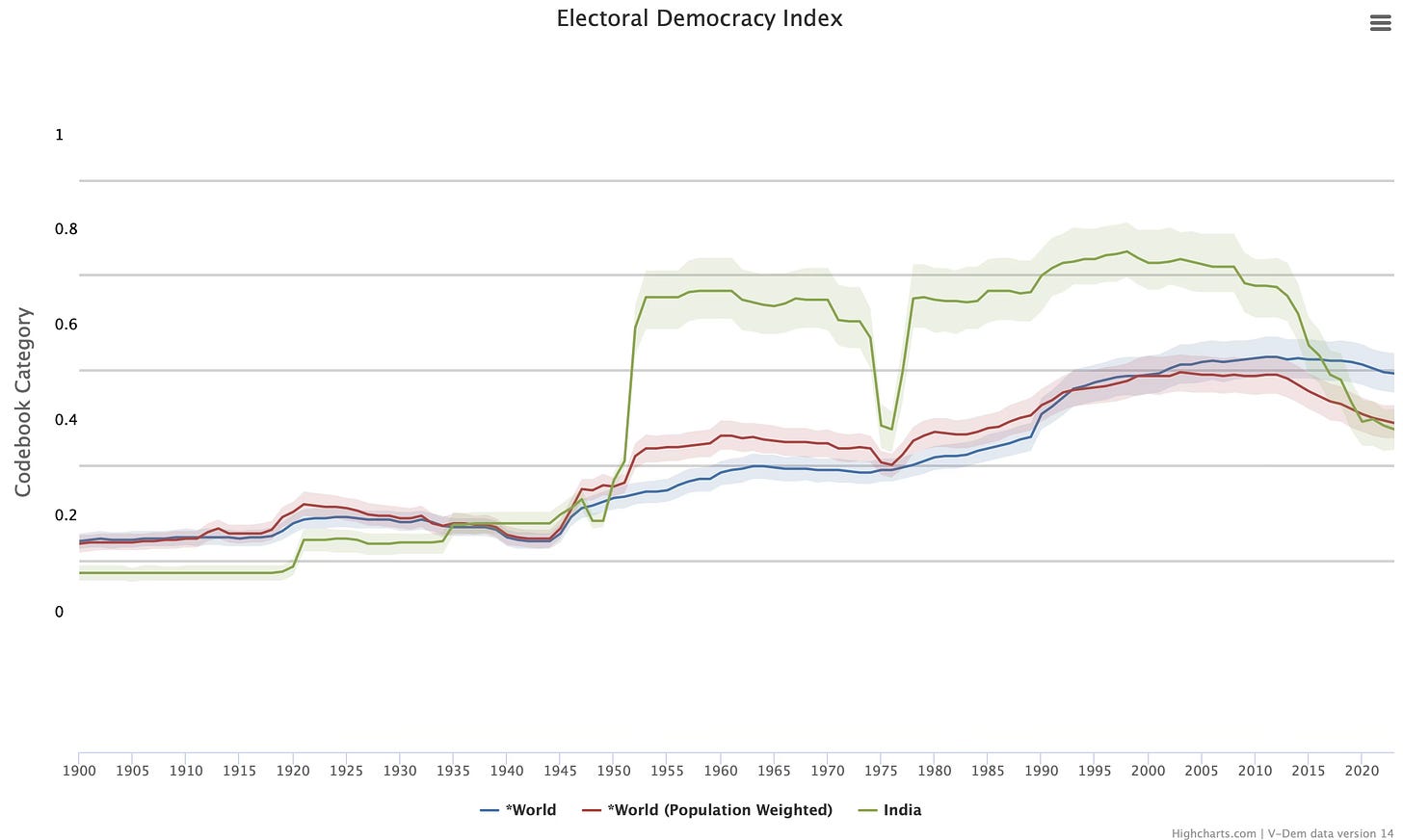

Below I show the V-DEM measure for ‘electoral democracy’ - which is their formal measure of free and fair elections plus freedom of speech and association. The first graph shows the world average, where all countries are weighted the same. A couple of things to note. For the first half of the twentieth century there is a mild bump up following WWI and then a decline through the 1930s (something important must have happened then I guess…). Then we have a rise in the postwar era, related to decolonisation, that tails off by the early 1960s. Finally, and most dramatically, we have the famous ‘third wave’ of democratisation that nominally begins with the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974 but really accelerates with the fall of the Berlin Wall and tops out in the first few years of the new millennium.

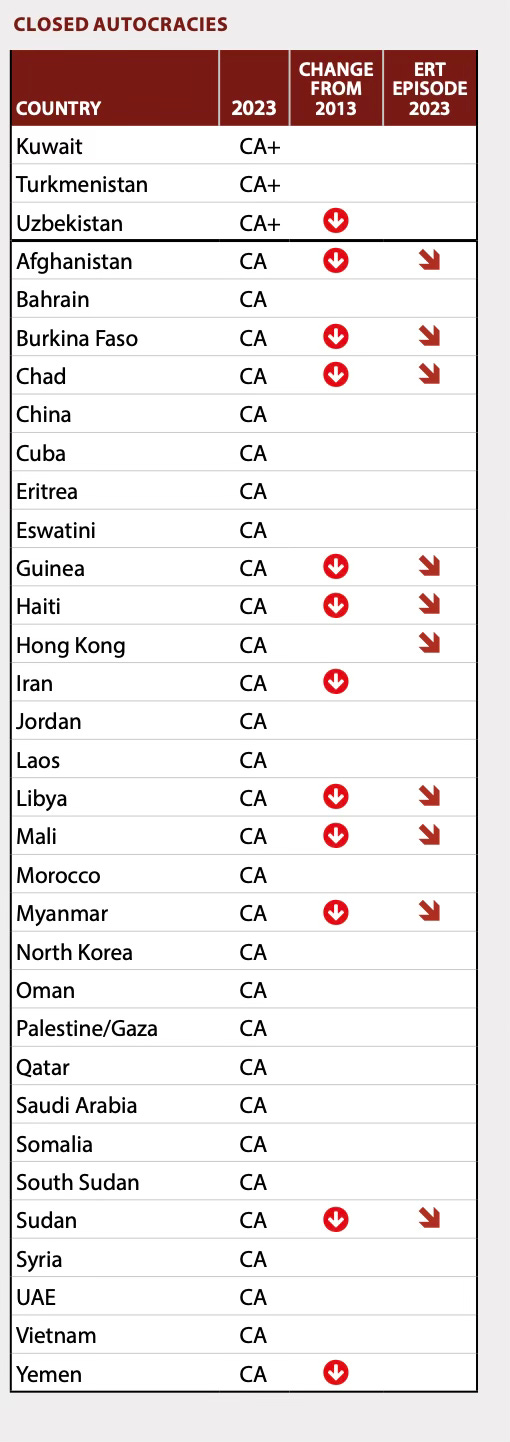

Overall that pushes ‘average’ electoral democracy from a score of about 0.15 in 1900 to about 0.55 by 2005. But then… a ‘democratic recession’ was upon us. There has been a decline since 2015 to just under 0.5. Now I don’t want to demean this. There has been lots of backsliding internationally - in Venezuela, Turkey, Russia, Hungary and so on. But that has been partly countered by improvements elsewhere - Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Honduras, Zambia. And, morbid as it is to say, many of the places that are currently experiencing episodes of ‘autocratisation’ are already highly closed autocracies, as this figure from V-DEM indicates.

The last few years may technically have been a democratic recession in the economic sense of two quarters of zero or lower growth. But I’m much more cautious about the idea of being in a democratic depression. So, given the very shallow nature of the democratic ‘recession’, why are people so worried?

Well for one, the more democratic countries undergoing downturns are big, economically important ones - Turkey, Venezuela, Poland etc but also at various points similar arguments have been made about Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, and even the United States. But in particular, one country stands out - India under Narendra Modi.

You can see the importance of India if we look at the V-DEM average electoral democracy index but now weighted by country population. Obviously China and India are huge contributors to this but since China’s population as a share of global population has been in decline for several decades that should help ‘average weighted electoral democracy’ by reducing the importance of this large authoritarian country.

But when we look at the red (weighted) versus the blue (unweighted) line we see the red line drop quite sharply since 2010. And this is essentially the work of India, whose population as a share of world population has remained steady.

That can be seen very clearly in the following figure that pulls out India (the green line). Here we see electoral democracy shooting up after Independence, collapsing briefly in Indira Gandhi’s state of emergency but sustained high in the 1990s and early 2000s. And then since 2010 a collapse down to state of emergency levels.

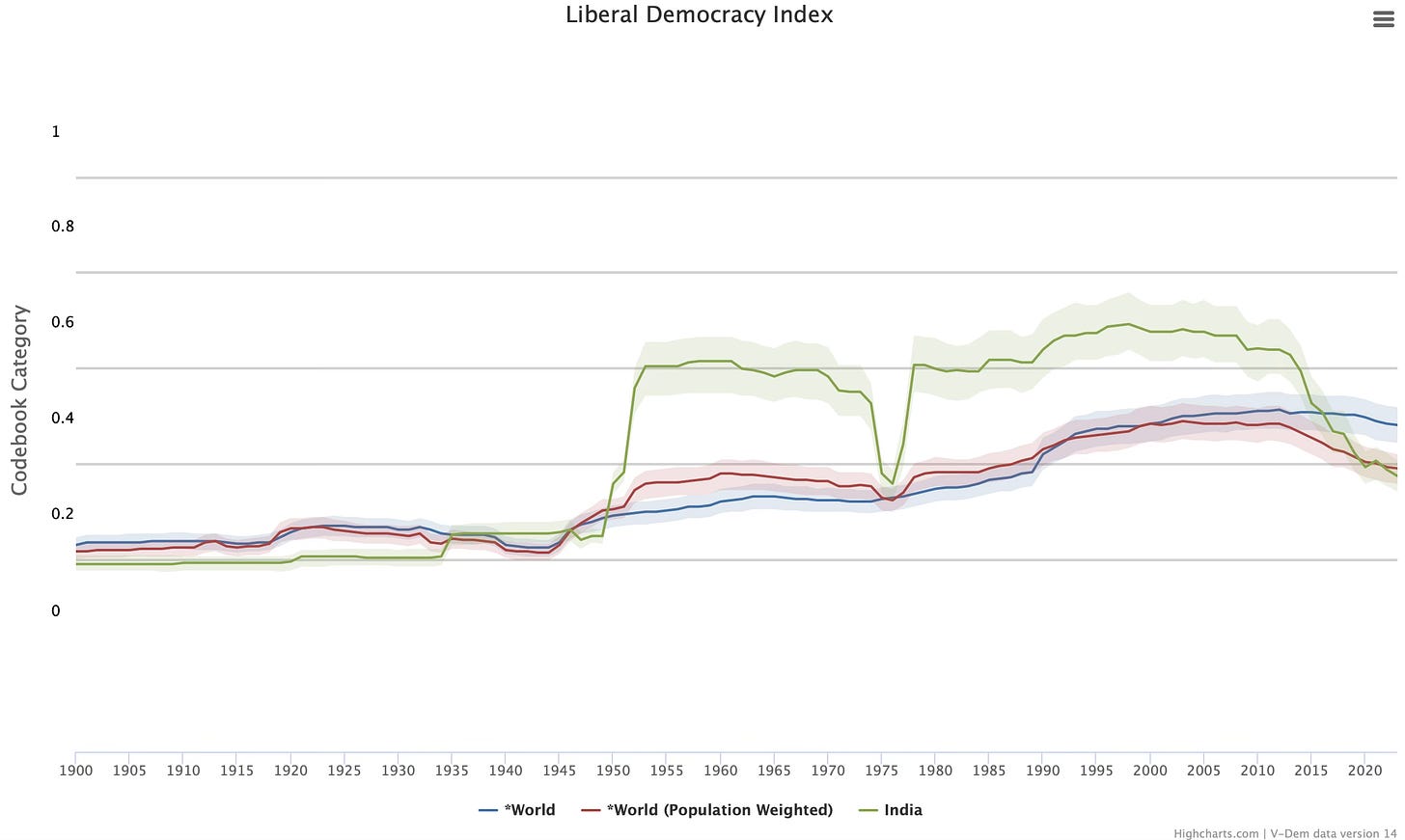

We see a very similar story if we use V-DEM’s liberal democracy index instead, which adds various measures of equality before the law, and so on.

So, a huge amount of the story of the democratic recession, at least in terms of how many people it affects, is attributed by V-DEM to the era of BJP governance and the success of Narendra Modi. That rise seemed unstoppable earlier this year, as major opponents were arrested on various charges, including the Chief Minister of Delhi, Arvind Kejriwal, on a money-laundering case and the leader of the opposition, Rahul Gandhi, on accusations of defaming Modi.

But things in mid-2024 turned out rather better than feared for those concerned about Indian democracy. Gandhi had his conviction stayed and Kejriwal was released (after several months of jail, to be sure). But most surprisingly of all, Modi’s party performed poorly. The BJP had won 303 out of the 545 seats in the Indian Parliament - the Lok Sabha - in 2019, well above what it needed for a majority. They were confident of doing much better this year - indeed they had the slogan Abki Baar 400 Paar, which means ‘this time surpassing 400’. So how did they fare?

Yeh, not so well. The BJP won just 240 seats. They had not surpassed 400 seats, they had in fact lost 63. They only returned to office in alliance with their allies in the National Democratic Alliance, which collectively had slipped from 353 seats to 293, a much slimmer majority. Now we shouldn’t read too much into this. For the next few years, Modi remains PM and his alliance will govern. But the Indian population were not cowed by the arrests of opposition leaders. Indeed, the opposition alliance increased their number of seats from 91 to 234 seats.

We don’t know yet how V-DEM and other coders will alter their subjective ratings of Indian democracy in 2024. The first half didn’t look great, what with the arrests and Modi’s claims that the Congress Party would favour ‘infiltrators’. The election itself though showed a still very competitive electoral system that surprised most observers. If it is to be the ‘Indian Century’, then the future of global democracy may in the end depend rather more on how the 2024 Indian election played out than that conducted half a world away in America later that year.

The ‘year of democracy’ narrative was always a double-edged sword. Yes it was important to note that 2024 was the year when most people ever could vote. That’s good news! But it also may have fooled us into thinking any one year could ever be determinative of the history and future of democracy. Democracy is not so fragile.

So, now might be as good time as any to mention that my next book, under contract with Viking/Penguin, will take very seriously the very long and unpredictable journey of democracy over the millennia. Like any natural history, there have been periods of rapid expansion followed by shocks and decline. Democracy is a robust system - it will not live or die on the outcome of any one year. But it’s not inevitable. It is a human invention - as creative but as frail as we are.

Happy New Year. And let’s hope this is one in which democracy creeps ever further away from that proverbial cliff.