Today is the launch day for the chapter on political inequality that Jane Gingrich and I have written for the Institute of Fiscal Studies Deaton Review on Inequality. We’ll be presenting some of the key findings at a webinar this afternoon and you can read the full document here. But what’s the point of a Substack if you can’t use it as a TL;DR for longer work? So dig in here for an abbreviated version, to whet your appetite for the whole 22,000 word monster.

The Deaton Review is an enormous, wide-ranging behemoth - an analysis of inequality in all its forms in the UK. There are wonderful chapters on trade, gender inequality, labour market inequality, and so forth. You should take the weekend to read them! But Jane and I were asked to do something a little different - to think about political inequality in the UK.

Political inequality sounds on the face of it like something simple. An analogue of economic inequality for politics. The comfortable rich, the just-about-managing, the left-behind, just in political form. But what form?

It turns out that political inequality is remarkably hard to define in a simple way. Because politics is not a resource that we can count, divide up, and analyse like income or wealth. We can’t easily create a political ‘Gini’ index. We can’t talk about the ‘politics share’ of the top one percent. Politics is harder to measure because it’s not exactly clear what… well what we’re trying to measure. Do we care about who votes or who decides? About what our MPs look like or who they ‘really’ work for?

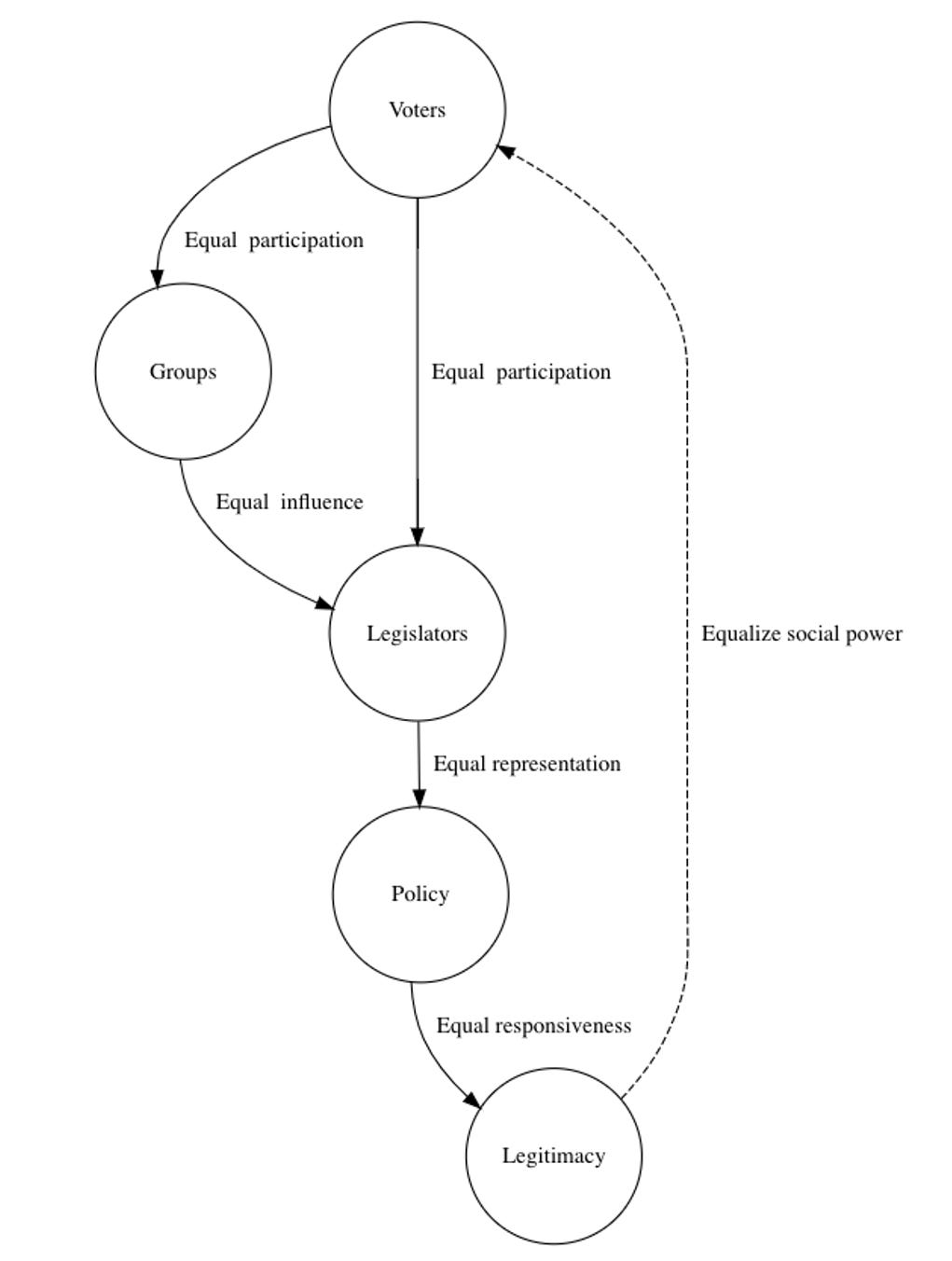

Here’s a little figure we created for our chapter that sets out the different places in the political process we could try to identify ‘political inequality’. You can see it is a chain from political inputs - turning out to vote and choosing who to vote for - to outputs - the policies that get made and how we feel about them. And in the middle of course are everybody’s favourite people - politicians. There’s many a slip twixt cup and lip and Westminster is plenty slippery.

So, when we’re talking about political inequality in the UK we might mean different things and end up talking past one another. Are we talking about whether everyone has an equal ability to participate in the political process. Are we talking about whose views get represented in the form of MPs and the policies they make. Do we want out MPs to look like us, or act on behalf of us, or both? Or more cynically, neither? Or are we talking about the degree to which politicians are equally responsive to voters and produce policies they are happy with? And how, if at all, is this connected to economic inequality in the UK?

Too many questions I know. I like questions. But you might, having read this far, wish for answers. So, enough throat-clearing, what do we find?

Here is the key take-home. Britain has become substantially more economically unequal since the 1960s, with most of the increase in the 1980s and 1990s. But today our politics is less defined by income and wealth than for generations. This is the political paradox in the title of this post. Now of course it’s rather more complicated than that but let’s start with the basic patterns.

Jane and I examined over half a century of British Election Study surveys to see how whether people vote and who they vote for had changed over the long-run. We wanted to find out how fairly basic demographics, many of which are strongly connected to socio-economic status, predict turnout and vote choice over time.

To do so, we had to harmonise some of the data to make it comparable across waves of the survey. For income, we match people to their income ‘quintile’ in the survey (i.e. we divide the survey into five groups by income and score people that way). For education, we use a three point scale: lower secondary education (GCSEs/O-Levels) or less; upper secondary education (A-Levels/Highers); and university degree. And then we also have measures of age, gender, and homeownership, which fortunately are consistent concepts across time!

I’m about to show some frightening looking figures. Each figure represents the relationship between one of these variables (e.g., income) and our outcome variable (individual turnout or vote choice) for each survey year, controlling for the other variables. As we’ll see the latter point is important - what looks like, for example, an effect of age, could instead be connected to education if age and education are correlated (which they very very much are in the UK). For the stats nerds among you, this is a simple linear probability model so you can interpret the y-axis directly as a change in probability.

<A quick aside - for vote choice, we will use the probability of voting Conservative but because UK politics has mostly been dominated by the two main parties, this is very similar to the inverse of having used voting Labour as our indicator>

OK, let’s begin with the paradox - we are more economically polarised than since before the Second World War but we are less politically polarised by income. Rich and poor have parted ways in income and wealth but become closer in voting behaviour.

If you read my previous Substack post, you will have seen this figure before. The way to interpret it, is that moving from the lowest to the top income quintile (a four-point shift) used to be associated (save for the late 1970s) with a twenty to thirty percent point higher probability of voting Conservative. That was also very much true in the Blair and Cameron era too. So at that time there was perhaps no paradox - economic polarisation was high and so too was political polarisation by class. But in 2019 the relationship between income and voting collapsed.

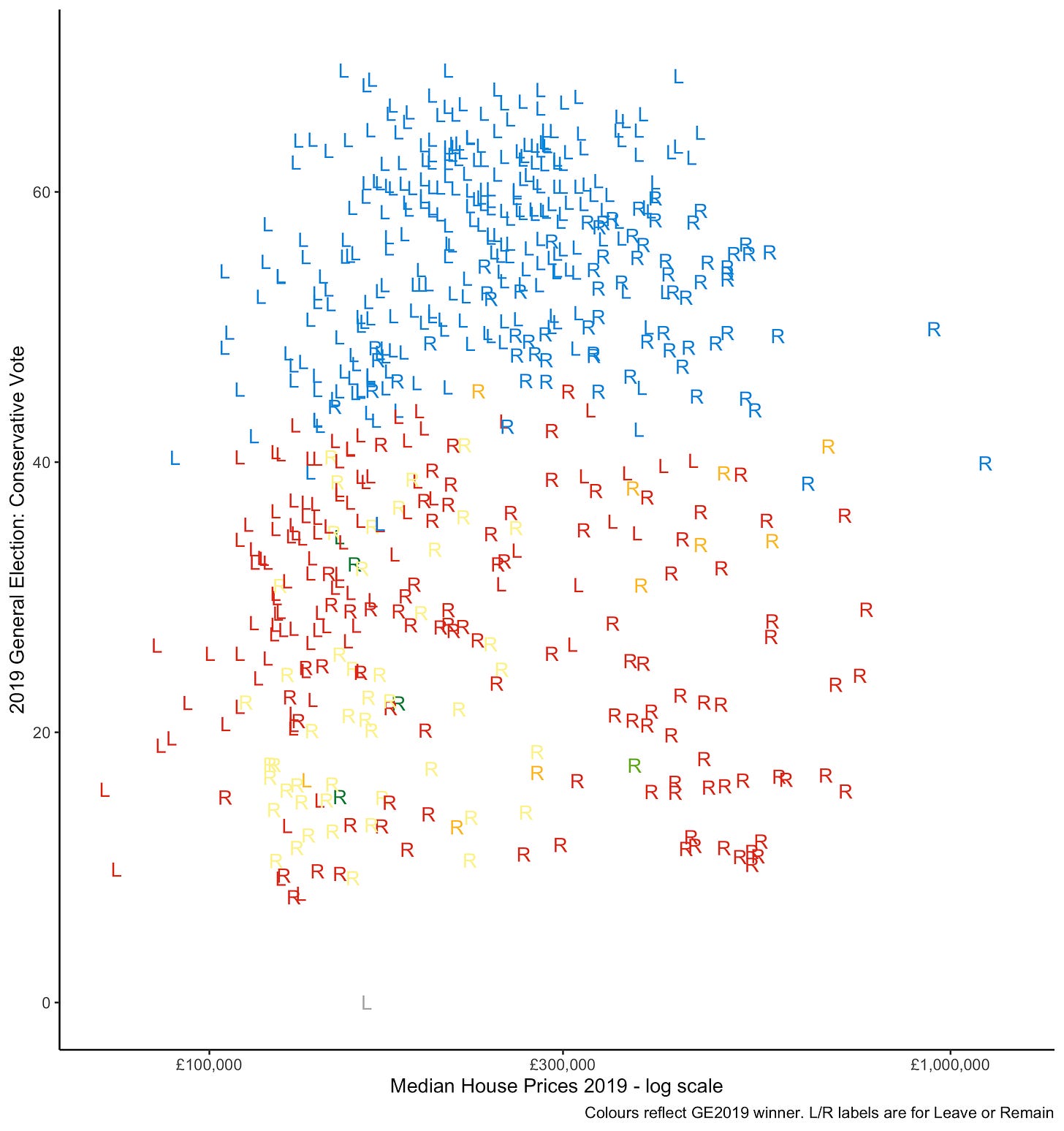

A similar story played out at the constituency level. Again here are two figures from my previous Substack post - the relationship between house prices and Conservative vote across constituencies in 1997 and again in 2019. In 1997, the 108 constituencies with the lowest house prices in England ALL voted for Labour and 43 out of the 40 most expensive constituencies voted Conservative.

And, here’s 2019. The relationship has vanished.

Another way of looking at this is the overtime correlation between local wealth and local voting in the UK. Here it’s clear it has been in substantial decline over the past decade. A rough doubling of house prices (a log point shift) was worth around twenty percent points to the Conservatives from 1997 to 2010. But by 2017 this had more than halved and by 2019 there was barely a relationship at all.

We can see a similar, albeit weaker, pattern if we look at homeownership - another key aspect of socio-economic status. Here we are just using a binary indicator so we can’t distinguish between owners of cheap and expensive houses. But what we do see is a long-running decline in the importance of homeownership for the Conservative vote from a twenty-point advantage in the 1960s through 1980s to around a ten point one today.

The message of the past few years of British politics is that income and wealth - our traditional class markers - matter substantially less for voting behaviour than they used to. And to reiterate, that should surprise us a bit since income inequality widened substantially over the past half-century. When people tell you that inequality polarises us, I’d be cautious. That’s not obvious from this data.

But here’s the thing. Everybody in Britain hates each other. OK that’s a little strong. But it doesn’t feel like a less polarised country. We have, it seems, just polarised around something else. And any follower of British politics can guess what that is - age and education. Which, as it turns out, in Britain are kind of the same thing.

Let’s start with age. Here I want to show two graphs in quick succession. The first is the relationship between age and voting Conservative not controlling for anything else. So this is what you would see if you naively assumed age wasn’t related to anything else. Reading along the y-axis, a year of age ‘made you’ 0.3 percent points more likely to vote Conservative all the way from 1964 to 2010 more or less. And then there is a huge jump for 2017 and 2019 to 0.7 percent points. In normal language, someone two decades older would have been six percent points more likely to vote Conservative through most of the postwar era and then suddenly fourteen percent points more likely in 2017. That’s a pretty big difference!

But like many shocking correlations, it’s not quite right. Once we control for income, gender, homeownership, and education (especially education) we see the following.

As someone important said in 2017 - “nothing has changed.” We are not any more divided by age than we were, as long as we think about what goes along with age in Britain. And that is education. Especially university education. Recent cohorts of twenty-somethings have been split roughly evenly between graduates and non-graduates, in part because of Tony Blair’s ambition than fifty percent of young people should go to university. In my parents’ era, only around ten percent of people went to university. And a majority then left school at sixteen. Which is not easy these days. And so, our murder-mystery is at an end. The culprit for political polarisation today? Education.

More educated people used to vote Conservative. A point shift here recall is either from lower secondary to upper secondary or upper secondary to university. So back in the 1960s, finishing your A-Levels meant being ten percent points more likely to vote Conservative - and going to university doubled that. And today? The precise opposite - you become ten points more likely to vote Labour for each shift in education. And that trend, which began at the end of the Thatcher years and was stable in the early years of the twenty-first century has suddenly accelerated.

One way of seeing that polarisation is to compare voting behaviour in marginal versus non-marginal electoral seats - if a demographic factor matters more in non-marginal seats that suggests parties’ core political coalitions are more polarised on that factor. And we see that in non-marginal seats in the last few elections, education has mattered more and income less.

When we look at Britain’s generational divides we are really seeing educational divides. Below is a figure taken from our analysis of the BES in 2019 alone. We split out under fifties and fifty and overs and look at the relationship between educational qualifications and voting.

You can stare at this figure a long time to look for an important difference between under and over fifties - education has basically the same impact (except maybe, maybe A-Levels). The baseline category in these figures is people without qualifications. And we can see that compared to them, people who went to university, regardless of their age were far far less likely to vote Conservative. The Conservatives didn’t have a young people problem, they had a degree-holder problem - there are just way more degree-holders among the young. Or put differently, Labour didn’t have an old people problem - they had a problem holding onto the votes of those with ‘lower’ educational qualifications regardless of age.

So we have a further paradox. Access to higher education in the UK is less unequal than it was in the past - so one dimension there is less educational inequality. But there is more political polarisation around education.

I want to emphasise there is no simple translation between the way that resources or opportunities that people have are equally or unequally distributed and how that filters into political polarisation as we usually understand it. And that means we need to be careful before we make great claims about how if we resolved inequality in Britain we’d all get along. The evidence if anything suggests the opposite. That of course doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t care about lowering economic or educational inequality for other moral (or otherwise) reasons. But we shouldn’t kid ourselves about the political impacts.

OK, we’re not more politically polarised. But does economic inequality really not matter for political inequality? It does, indeed. But for who shows up to vote not who they vote for. And if you care about participatory democracy that might be crucial.

Below is a gallery of the relationship between our demographic factors and turning out to vote back to 1964. Here the patterns are much more striking and consistent. Everywhere we look, higher socio-economic status (and age!) is associated with being more likely to show up at the voting booth.

Turnout inequality is high and has been getting higher since 1997. If economic polarisation is negatively impacting politics anywhere, it’s here. In fact, the reason why it might not be feeding into political polarisation is that the poor are simply not turning up to vote at all. If we are to try to combat the negative effects of inequality on politics, we might want to start here, by making it easier for younger, lower income, less-educated, and non-homeowning citizens to vote. I will simply note here that this does not appear to be the direction of travel implied by the introduction of voter ID and in particular the seeming favouritism towards the types of ID that older people are more likely to have.

OK enough about inputs. What about Parliament and Whitehall? Do our representatives represent us more effectively than in the past? There is some good news here. Generally speaking, Parliament looks a lot more like us than it used to - so this form of political inequality seems to be in abeyance.

The first thing worth noting is the substantial improvements in the gender balance of Parliament and its representation of ethnic minorities, especially in contrast to the 1980s. Parliament has also come closer in its age profile to the population but sadly that’s just because we’re all getting older. In educational terms, MPs are less likely to have attended private school or Oxbridge than they were but are more likely to have gone to university - though that is, of course, also true for the population. And finally, MPs have largely tracked occupational changes in the population, except in terms of coming from the professions, which they are less likely to do over the past few years.

So that’s good news right? Well, it doesn’t seem to making us a huge deal happier. Jane and I also looked at how the voting public felt about the political system in BES surveys back to the 1980s. It won’t surprise you that were are less and less happy. But there’s a twist…

The BES asks if respondents feel that ‘people like them’ have ‘no say’ in politics. We break down the average response by different demographic groups in the above figure. The first thing to say is that we are less happy - around ten percent points more likely to agree with that prompt than in 1987.

But I promised a twist. Over the past couple of elections - the ones that have been less polarised in voting behaviour - we have also been less polarised in how we feel. In particular, those who previously felt most represented - degree-holders, high earners, and younger citizens - have shifted to feeling less represented. There has been a slight increase in feeling represented among older and lower income citizens. Despite high economic inequality, once again we’re all more like one another politically. Equally discontent.

There’s lots lots more in the chapter, which I hope this post has given you the urge to read! We talk about policy outputs - how have education, housing, and welfare policies shifted over the past few decades? And of course, we have a much more extensive discussion of how to think about political inequality. The chapter is here.

In my next couple of Substack posts, hopefully this side of Christmas, I’ll look more on intergenerational divides in the UK and how people of different ages think about social mobility, home-building, and the sacrifices they made during COVID using original survey data. And I’ll also be looking at how people feel about wealth taxation. But for now, go and read the chapter!

(In 1997) 43 out the 40 most expensive areas voted Conservative? That's a stronger correlation than I thought possible!

(Obviously it goes without saying that overall this very good work.)